the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Last ice sheet recession and landscape emergence above sea level in east-central Sweden, evaluated using in situ cosmogenic 14C from quartz

Bradley W. Goodfellow

Arjen P. Stroeven

Nathaniel A. Lifton

Jakob Heyman

Alexander Lewerentz

Kristina Hippe

Jens-Ove Näslund

Marc W. Caffee

In situ cosmogenic 14C (in situ 14C) in quartz provides a recently developed tool to date exposure of bedrock surfaces of up to ∼ 25 000 years. From outcrops located in east-central Sweden, we tested the accuracy of in situ 14C dating against (i) a relative sea level (RSL) curve constructed from radiocarbon dating of organic material in isolation basins and (ii) the timing of local deglaciation constructed from a clay varve chronology complemented with traditional radiocarbon dating. Five samples of granitoid bedrock were taken along an elevation transect extending southwestwards from the coast of the Baltic Sea near Forsmark. Because these samples derive from bedrock outcrops positioned below the highest postglacial shoreline, they target the timing of progressive landscape emergence above sea level. In contrast, in situ 14C concentrations in an additional five samples taken from granitoid outcrops above the highest postglacial shoreline, located 100 km west of Forsmark, should reflect local deglaciation ages. The 10 in situ 14C measurements provide robust age constraints that, within uncertainties, compare favourably with the RSL curve and the local deglaciation chronology. These data demonstrate the utility of in situ 14C to accurately date ice sheet deglaciation, and durations of postglacial exposure, in regions where cosmogenic 10Be and 26Al routinely return complex exposure results.

- Article

(3300 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(88289 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The pacing of the retreat of ice sheets in North America and Eurasia, since their maximum expansion during the last glaciation, remains an active research field (e.g. Hughes et al., 2016; Stroeven et al., 2016; Patton et al., 2017; Dalton et al., 2020, 2023). Understanding the triggers and processes causing the demise of these ephemeral ice sheets yields the best blueprint for understanding the future behaviour of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets in a warming climate. Coupling the behaviour of deglaciating ice sheets over the course of the Late Glacial and Early Holocene to increasingly precise climate reconstructions, including climatic events, requires increased precision in ice sheet reconstructions (e.g. Bradwell et al., 2021). Precision can be enhanced through coupling geomorphological mappings of ice sheet margins (such as moraines, grounding zone wedges, lateral meltwater channels, and ice-dammed lake shorelines and spillways) with numerical field constraints from a diverse array of dating techniques (e.g. Stroeven et al., 2016; Bradwell et al., 2021; Regnéll et al., 2023).

Ice sheet reconstructions, especially in North America, have become highly detailed through radiocarbon dating (Dyke et al., 2002; Dalton et al., 2020). With the advance of offshore imaging of glacial geomorphology (Greenwood et al., 2017, 2021; Bradwell et al., 2021), radiocarbon dating has received a renewed upswing in recent years (e.g. Dalton et al., 2020; Bradwell et al., 2021). However, large landscape areas lack radiocarbon age constraints on ice sheet retreat because of an absence of datable organic material. Fortunately, optically stimulated luminescence ages on buried sand layers (e.g. Alexanderson et al., 2022) and cosmogenic nuclide-apparent exposure ages on exposed bedrock and erratics have narrowed some of the gaps (e.g. Hughes et al., 2016; Stroeven et al., 2016; Dalton et al., 2023). In studies using cosmogenic nuclides, an “apparent” exposure age is derived from a simple calculation from the nuclide concentration under consideration (Lal, 1991; Gosse and Phillips, 2001). Correctly interpreting the exposure age relies on modelling that considers geological factors that can reduce the nuclide concentration relative to the time since initial subaerial exposure (such as erosion and burial by glacial ice, water, snow, and/or soil; Gosse and Phillips, 2001; Schildgen et al., 2005; Ivy-Ochs and Kober, 2008). Exposure dating is the only technique available in regions where ice sheet erosion has left the surface bare or covered by a thin drape of till. Kleman et al. (2008) show that for Fennoscandia, these conditions are widespread in coastal regions where ice accelerated towards its streaming sectors and where wave wash during glacial rebound further thinned or removed pre-existing sediment covers.

Coastal sectors in formerly glaciated regions provide sites important to the study of paleoglaciology. They offer an abundance of bedrock exposures from which patterns and processes of subglacial erosion can be studied through cosmogenic nuclide exposure dating (e.g. Hall et al., 2020). Also, because of the interplay with postglacial sea levels, coastal areas yield data on glacio-isostatic rebound that are critical to the geodynamic modelling of Earth rheology and thicknesses of former ice sheets (e.g. Lambeck et al. (1998, 2010) and Patton et al. (2017) for Fennoscandian examples). Geodynamic models require validation against measurements of vertical crustal motion (Steffen and Wu, 2011), such as those provided by recent global positioning system (GPS) measurements (e.g. Lidberg et al., 2010) and postglacial records of crustal rebound afforded by relative sea level (RSL) curves (e.g. Påsse and Andersson, 2005). The construction of RSL curves, detailing the history of land surface emergence from sea level, is traditionally done either using sediments accumulated in isolation basins at different elevations above sea level or by dating uplifted gravel beach ridges. Typically, isolation basins, and their sediments, show a progression from marine to brackish and finally to freshwater environments as they are uplifted through tidal levels (Long et al., 2011). Histories of land uplift above sea level are documented using microfossil and macrofossil analyses of isolation basin sediments and radiocarbon dating on macrofossils (Romundset et al., 2011). Uplifted beach ridges can be radiocarbon-dated from a variety of materials (Blake, 1993) but most confidently from driftwood, whalebone, and shells (e.g. Dyke et al., 1992). Gravel beach ridges have also been investigated using OSL (optically stimulated luminescence) and 10Be exposure dating even though, other than the highest beach ridge, they may be prone to clast reworking (Briner et al., 2006; Simkins et al., 2013; Bierman et al., 2018). A distinct advantage of constructing RSL curves using cosmogenic nuclides is that land surface emergence above sea level may be additionally dated from boulders (Briner et al., 2006) or bedrock (Bierman et al., 2018).

The potential for cosmogenic surface exposure dating of the last ice sheet retreat in recently glaciated low-relief cratonic landscapes would seemingly be high because of the frequent outcropping of glacially sculpted quartz-bearing crystalline bedrock. However, either the ice sheet may have been non-erosive, or the erosion was insufficiently deep to remove all the cosmogenic nuclide inventory from previous exposure periods. Apparent ages are therefore often older than indicated by radiocarbon dating (Heyman et al., 2011; Stroeven et al., 2016) because they include a component of nuclide inheritance. Apparent ages younger than indicated by radiocarbon dating can also occur if sampled rock surfaces have been shielded, for example by sediments, following deglaciation. Concentrations of 10Be and 26Al, in either bedrock or erratic boulders, often reflect complex exposure histories rather than simple deglacial exposure durations (Heyman et al., 2011; Stroeven et al., 2016).

In this study we use 14C produced in situ in quartz-bearing bedrock (in situ 14C) because it potentially circumvents an overt reliance on the need for deep erosion (> 3 m) to remove the inherited signal from previous exposure periods (Gosse and Phillips, 2001). Because of its short half-life of 5700 ± 30 years, inherited in situ 14C will decay if ice sheet burial at investigated sites during the last glacial phase (marine isotope stage 2; MIS2) exceeded 25–30 kyr, which is ca. five half-lives (Briner et al., 2014).

Some studies assessing changes in glacier and ice sheet extents over Late Glacial–Holocene timescales have used in situ 14C (Miller et al., 2006; Fogwill et al., 2014; Hippe et al., 2014; Schweinsberg et al., 2018; Pendleton et al., 2019; Young et al., 2021; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2022). In these studies, in situ 14C has been applied with other nuclides with longer half-lives, in particular 10Be, to unravel complex histories of glacier advance and retreat (e.g. Goehring et al., 2011) and spatial patterns in glacial erosion in mountainous terrain (e.g. Steinemann et al., 2021). Extensive regions formerly covered by ice sheets are characterized by low-relief and low-elevation terrain. The effectiveness of in situ 14C in dating ice sheet retreat in these non-alpine settings and in quantifying shoreline displacement from bedrock samples has not been previously assessed. The aim of this study is therefore to validate the use of 14C formed in situ in bedrock as a reliable chronometer by evaluating its performance in duplicating (i) a previously established Holocene RSL curve based on radiocarbon dating (Hedenström and Risberg, 2003; SKB, 2020) and (ii) the timing of deglaciation above the highest (postglacial) shoreline in nearby east-central Sweden according to reconstructions of deglaciation of the last ice sheet (Hughes et al., 2016; Stroeven et al., 2016).

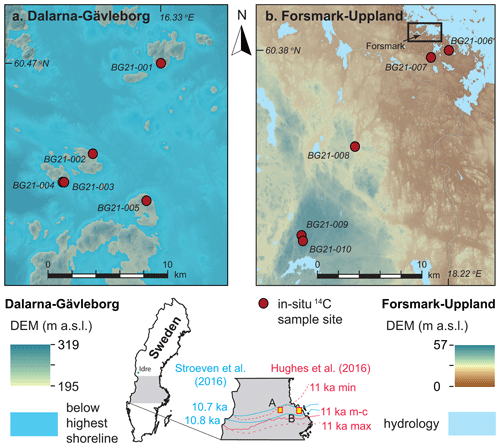

Our study is focused on east-central Sweden. This region includes low elevation and low relief terrain in Forsmark–Uppland and higher elevation and higher relief terrain in adjacent Dalarna–Gävleborg (Fig. 1). This region was selected because Forsmark is the location of a planned geological repository for spent nuclear fuel (e.g. SKB, 2022). As such, this region has been intensively studied and has a wealth of geologic data relevant to our study. This wealth includes in-depth analyses of bedrock and environmental properties, including influences of glacial and postglacial processes (e.g. Lönnqvist and Hökmark, 2013; Hall et al., 2019; Moon et al., 2020; SKB, 2020).

Figure 1Sample locations for in situ 14C dating in (a) Dalarna–Gävleborg and (b) Forsmark–Uppland. The five Dalarna–Gävleborg sample sites are located on what were islands above the highest postglacial shoreline (shown), whereas the five sample sites from Forsmark–Uppland are located below the highest shoreline (not shown because the entire area was submerged). See inset maps for locations of panels (a) and (b) and for the 10.7 and 10.8 ka retreat isochrones (blue) from Stroeven et al. (2016) and 11 ka (most-credible, minimum, and maximum) retreat isochrones (red) from Hughes et al. (2016). The rectangle in panel (b) approximately indicates the site selected for the planned geological repository for spent nuclear fuel at Forsmark. DEM with 2 m resolution, from lidar data (Lantmäteriet, 2020).

From spatio-temporal ice sheet reconstructions by Kleman et al. (2008), the study area was glaciated 16–20 times for a total duration of ca. 330 kyr over the past 1 Myr. The last deglaciation of the study area is well-constrained by two recent reconstructions that differ in their approach (Hughes et al., 2016; Stroeven et al., 2016). The Hughes et al. (2016) reconstruction relies primarily upon chronological constraints supplied from radiocarbon, thermal luminescence, optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), infrared stimulated luminescence, electron spin resonance, terrestrial cosmogenic nuclide (TCN), and U-series dating. Published landform data, mostly with respect to end moraines and generally accepted correlations of ice margin positions between individual moraines, provide complementary evidence. In contrast, the Stroeven et al. (2016) reconstruction combines geomorphological constraints for ice sheet margin outlines, including ice-marginal depositional landforms and meltwater channels, ice-dammed lakes, eskers, lineations, and striae, with chronological constraints supplied by radiocarbon, varve, OSL, and TCN dating. Whereas Hughes et al. (2016) reconstruct ice sheet retreat every 1 kyr and for every ice margin plot its position as “most credible”, “min”, and “max”, Stroeven et al. (2016) present ice margin positions for every 100 years inside the Younger Dryas standstill position (Stroeven et al., 2015). These marginal positions are temporally and spatially defined by the “Swedish timescale” clay varve record along the Swedish east coast (De Geer, 1935, 1940; Strömberg, 1989, 1994; Brunnberg, 1995; Wohlfarth et al., 1995). From Stroeven et al. (2016), the last deglaciation of the study area occurred at 10.8 ± 0.3 ka, which overlaps the timing of deglaciation of the study area from Hughes et al. (2016), within uncertainty (Fig. 1). The highest postglacial shoreline in east-central Sweden is located at a present elevation of ∼ 200 m a.s.l. in Dalarna–Gävleborg, which is ∼ 100 km west of Forsmark (SGU, 2015). The exposure duration of bedrock above the highest postglacial shoreline represents the time since local deglaciation. Hence, in situ 14C ages from bedrock above the highest postglacial shoreline should conform to the reconstructed deglaciation age of 10.8 ± 0.3 ka from Stroeven et al. (2016).

Below the highest postglacial shoreline, in the Forsmark–Uppland region, the last deglaciation occurred in a marine environment, and the landscape has progressively emerged above sea level through postglacial isostatic uplift. A RSL curve constructed from radiocarbon dating of basal organic sediments trapped in isolation basins along elevation transects describes the progressive emergence of the Forsmark–Uppland landscape above sea level (Robertsson and Persson, 1989; Risberg, 1999; Bergström, 2001; Hedenström and Risberg, 2003; Berglund, 2005; SKB, 2020). Ages calculated from in situ 14C from bedrock outcrops along an elevation transect would then mirror the Forsmark RSL curve for their corresponding elevations (but they would be slightly older because of nuclide production through shallow water before emergence).

A potential complication to the accurate exposure age dating of bedrock surfaces using in situ 14C in east-central Sweden is that the most recent period of ice sheet burial may have been insufficiently long to decay in situ 14C inventory inherited from prior exposure. Here, the extent of the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet during interstadial MIS3 and the timing of ice advance across the Forsmark region during late MIS3 are crucially important. Kleman et al. (2020) have identified ice-free conditions around Idre (330 km NW, up-ice, of our study area; Fig. 1) between 55 and 35 ka, which implies inundation of our study area by ice after 35 ka. Combined with a well-constrained final deglaciation age of 10.8 ± 0.3 ka (Stroeven et al., 2016), it appears that our study area has most recently (during MIS2) been inundated by glacial ice for, at most, 24 kyr. This inference is in line with results from ice sheet modelling indicating a 22 kyr duration of ice cover at Forsmark during MIS2 (SKB, 2020). Consequently, it is possible that in situ 14C concentrations may reflect subaerial exposure of bedrock in our study area during MIS3, in addition to Holocene exposure, resulting in an offset towards older ages relative to the RSL curve for Forsmark (Hedenström and Risberg, 2003; SKB, 2020) and the deglaciation chronologies of Hughes et al. (2016) and Stroeven et al. (2016).

3.1 Sampling of bedrock outcrops for in situ 14C measurements

We used the following sampling strategy to evaluate the accuracy of bedrock exposure ages derived from in situ 14C against the Forsmark RSL curve and the deglaciation of the last ice sheet in east-central Sweden. A rigorous scheme was applied to ensure that we avoided sampling quartz altered through hydrothermal processes that is likely to occur in major pegmatite intrusions; outcrops located in major deformation zones; and outcrop-scale veins, fractures, and adjacent rock volumes. Consequently, sampling was done on outcrops of metagranitoid from the early-Svecokarelian GDG-GSDG suite that dominates the Bergslagen lithotectonic unit (Stephens and Jansson, 2020). A petrological examination using transmitted light polarization microscopy was applied to thin sections to ascertain that the quartz was unlikely to contain multi-fluid-phase, vapour-phase, or solid-phase inclusions. All samples were collected using an angle grinder, which permits the sampling of hard crystalline bedrock isolated from outcrop edges, fractures, and quartz veins and consistently limits sample thicknesses to 3 cm.

We collected a total of 10 samples for in situ 14C analyses. Five of these were collected along a SW–NE transect near Forsmark (Fig. 1b). These outcrops were chosen because they span an elevation gradient of 9.4–56.0 m a.s.l., and the exposure ages derived from in situ 14C can therefore be evaluated against the Forsmark RSL curve. We collected a further five samples from locations above the highest shoreline (Fig. 1a) to determine the age of local deglaciation for comparison with published deglaciation chronologies (Hughes et al., 2016; Stroeven et al., 2016). Sample locations were logged on a 2 m resolution lidar digital elevation model (DEM) displayed in ArcGIS 10 on a tablet computer. A GPS add-in tool in ArcGIS 10 was used to record positional data within a horizontal precision of 2 m. The elevation of each sample location was extracted from the DEM and has a precision of tens of centimetres. The influence of these minor positional uncertainties on our 14C calculations is trivial, and none of the sample sites are influenced by topographic shielding that could reduce the accumulation of 14C in bedrock.

Each sampled bedrock outcrop formed a local topographic high, which minimizes the risk of burial by soil and snow (Supplement file S1). Moss mats were present on all sampled outcrops. Although we avoided sampling bedrock that was moss-covered, we cannot be certain that moss mats did not formerly cover the sample sites. Given a compressed thickness of 0.5 cm and an estimated density of 0.7 g cm−3, this may have contributed to a shielding of the sampled rock surfaces of 0.35 g cm−2, which is negligible and is therefore excluded from our age inferences.

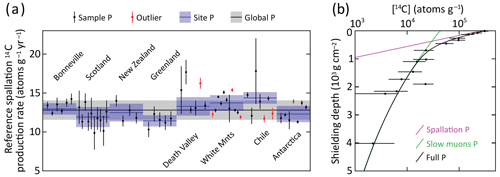

Figure 2Production rate calibration of 14C in quartz. (a) Reference spallation 14C production rate calibration based on data from Schimmelpfennig et al. (2012), Young et al. (2014), Lifton et al. (2015), Borchers et al. (2016), and Phillips et al. (2016), corrected per Hippe and Lifton (2014) and compiled in Koester and Lifton (2023). An uncertainty-weighted production rate is calculated for each of the eight sites. Outliers, which are not included in the uncertainty-weighted production rates, are determined based on the requirement that there should be at least three samples yielding a reduced chi-square statistic with a p value of at least 0.05 for the assumption that the individual production rates from a site are derived from one normal distribution. For , but not the uncertainty weighting, we use the largest of the sample-specific production rate uncertainty based on the 14C concentration uncertainties and 5 % of the sample production rate. This procedure does not punish samples with low measurement uncertainties, which otherwise risk exclusion as outliers. We adopt a global reference spallation 14C production rate of 12.81 ± 1.25 atoms g−1 yr−1, calculated as the arithmetic mean of the eight site production rates with the uncertainty being based on an uncertainty-weighted deviation of all included single-sample production rates, excluding outliers. (b) Calibration of 14C production rate from muons based on the data of Lupker et al. (2015). The calibration is based on the method used in the CRONUScalc calculator (Marrero et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2016). The figure shows the best-fit 14C concentration profiles produced from spallation, slow muons, and full production. The best fit yields a near-zero production from fast muons (cf. Lupker et al., 2015). The production rate calibration has been carried out using the expage calculator version 202403 (Heyman, 2024) in an iterative way to make the global reference spallation 14C production rate converge with the production rate from muons.

3.2 Laboratory preparation for accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS)

Samples were physically and chemically processed at the Purdue Rare Isotope Measurement Laboratory (PRIME Lab) at Purdue University, USA. Concentrations of in situ 14C were determined from purified quartz separates through automated procedures (Lifton et al., 2023). Approximately 5 g of quartz from each sample was added to a degassed LiBO2 flux in a reusable 90 % Pt10 % Rh sample boat and heated to 500 °C for 1 h in ca. 6.7 kPa of research purity O2 to remove atmospheric contaminants, which were discarded. The sample was then heated to 1100 °C for 3 h to dissolve the quartz and release the in situ 14C, again in an atmosphere of ca. 6.7 kPa of research purity O2 to oxidize any evolved carbon species to CO2. The CO2 from the 1100 °C step was then purified, measured quantitatively, and converted to graphite for 14C AMS measurement at PRIME Lab (Lifton et al., 2023). To test for data reproducibility, sample BG21-002 was randomly selected to undergo laboratory preparation and AMS a second time. Measured concentrations of in situ 14C are calculated from the measured isotope ratios via AMS following Hippe and Lifton (2014; Table 1).

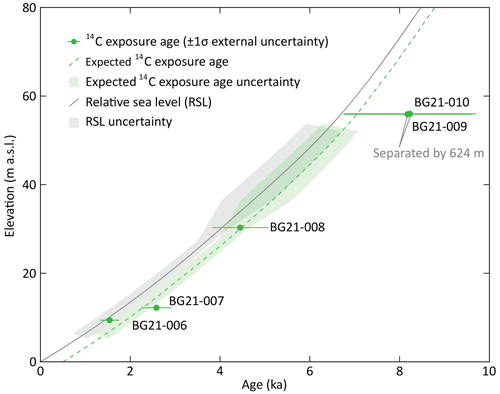

Figure 3Apparent 14C exposure ages for five Forsmark samples from below the highest shoreline (Fig. 1b; Table 2) with 1σ external uncertainties. The expected exposure ages are calculated assuming the RSL curve is correct, the 14C spallation production rate is correct, partial exposure as the sample approaches the water surface, and full postglacial exposure for the duration above sea level. Hence, the expected exposure age curve is a few hundred years older than the RSL curve. The RSL curve is from SKB (2020), and uncertainties for the 1–6 ka interval are calculated from the original radiocarbon data in Hedenström and Risberg (2003). The RSL uncertainty envelope is also transposed onto the expected exposure age curve.

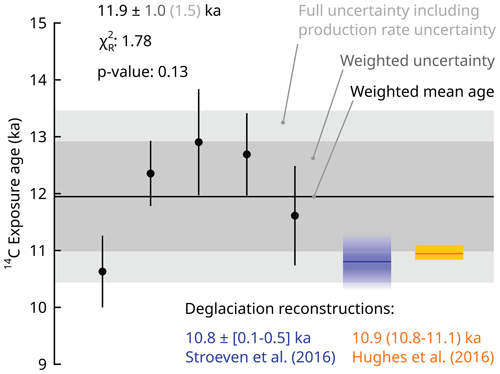

Figure 4Exposure ages from samples above the highest shoreline (Fig. 1a; Table 2). The individual samples (filled black circles) display a 1σ internal uncertainty (measurement uncertainty; black lines). For the repeat sample BG21-002, the exposure age is calculated with a weighted mean 14C concentration using a 2 % uncertainty. The cosmogenic nuclide ages yield a reduced chi-square statistic of 1.78 and a p value of 0.13 based on internal uncertainties, which indicates that they are from the same population. The colour gradient for the Stroeven et al. (2016) deglaciation chronology indicates the 0.1–0.5 ka uncertainty range, whereas the uncertainty for the Hughes et al. (2016) chronology reflects the maximum and minimum estimates for deglaciation of the study area, which are unequally distributed around the most credible estimate (orange line).

3.3 Exposure age calculations

The expage calculator version 202403 (Heyman, 2024) is used to calculate apparent exposure ages. It is based on the original version 2 CRONUS calculator (Balco et al., 2008), the LSDn production rate scaling (Lifton et al., 2014), and the CRONUScalc calculator (Marrero et al., 2016), using the geomagnetic framework of Lifton (2016) with the SHA.DIF.14k model for the last 14 kyr. Exposure ages are calculated using resulting time-varying 14C production rates accounting for decay and interpolated to match the measured 14C concentration. The production rate from muons is calibrated against the Leymon High core 14C data of Lupker et al. (2015), and the production rate from spallation is calibrated against updated global 14C production rate calibration data (Schimmelpfennig et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014; Lifton et al., 2015; Borchers et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2016; Koester and Lifton, 2023, 2024). This calibration is done iteratively for spallation and muons to reach convergence using the expage production rate calibration methods (Fig. 2; Heyman, 2024).

Exposure age calculations along the Forsmark–Uppland transect account for 14C production during emergence through shallow water. Burial of sampled surfaces by snow is excluded from the age calculations for all sample sites because we know neither how snow burial depths and durations vary between sites nor how they vary through time. The effect of snow burial would be to slightly decrease cosmogenic nuclide production in the underlying rock surface (Schildgen et al., 2005), and we have minimized this effect through our sampling strategy.

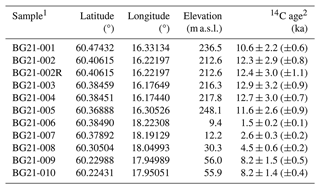

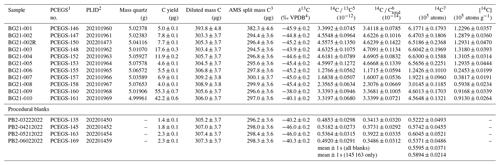

Table 1In situ 14C sample measurement details.

1 Purdue Carbon Extraction and Graphitization System. 2 PRIME Lab ID. 3 Mass graphitized for AMS analysis after a small aliquot (ca. 9 µg C) was taken for an offline stable C isotopic analysis. 4 VPDB stands for Vienna Peedee Belemnite. 5 Measured relative to OX-2 standard. 6 Corrected for mass-dependent graphitization blank (based on AMS split mass C) and stable C composition. 7 Sample values calculated using diluted mass C and corrected for mean procedural blank (all blanks).

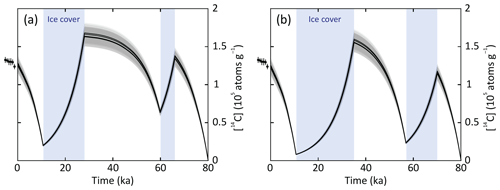

Figure 5Modelled in situ 14C concentration evolution over the last 80 kyr in the five samples (BG21-001–BG21-005) from above the highest shoreline. The 14C development is modelled assuming no glacial or interglacial erosion, continuous exposure to cosmic rays during ice-free periods, and full shielding from cosmic rays (no 14C production) during periods with ice cover. The points just left of the plots display the measured 14C concentrations for the six sample measurements (Table 1). (a) Scenario with short periods of MIS4 and MIS2 ice cover from 66 to 60 ka and from 28 ka to deglaciation around 10.7 ka. (b) Scenario with longer periods of MIS4 and MIS2 ice cover from 70 to 57 ka and from 35 ka to the deglaciation around 10.7 ka. Due to the rapid decay of 14C (half-life of 5700 ± 30 years), both scenarios yield similar end-point concentrations of 14C that overlap, within uncertainties, the measured sample concentrations.

Analytical results for in situ 14C samples and procedural blanks are presented in Table 1. The mean and standard deviation are used to correct measured 14C sample inventories (Table 1) because procedural blanks are well-constrained during the analytical time frame. Inferred ages for the five in situ 14C samples from the Forsmark–Uppland transect (i.e. below the highest postglacial shoreline) are shown relative to the Holocene RSL curve for Forsmark and the expected in situ 14C exposure age curve considering subaqueous cosmogenic nuclide production (Fig. 3; Table 2). Exposure age uncertainties are large with internal uncertainties (measurement uncertainties; Balco et al., 2008) of 5 %–9 % and external uncertainties of 13 %–25 % (also including production rate uncertainties, which are high relative to 10Be; Borchers et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2016). Apparent exposure ages increase consistently with elevation and match expected ages within uncertainty. The two highest samples have near-identical apparent exposure ages and elevations. However, these samples provide independent ages because they are horizontally separated by 624 m (Fig. 1b). There is good agreement between ages inferred from these in situ 14C data and the RSL curve constructed from organic radiocarbon dating of isolation events (Hedenström and Risberg, 2003; SKB, 2020).

Apparent exposure ages for the five in situ 14C samples located above the highest shoreline in Dalarna and Gävleborg (Fig. 1a) are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 2. The weighted mean age from all five samples is 11.9 ± 1.5 ka. These data display a of 1.78 and a p value of 0.13 based on 1σ internal uncertainties, which does not support a rejection of the hypothesis that the apparent exposure ages represent the same population. In addition to the samples being from the same population, the exposure ages are consistent, within uncertainty, with the expected deglaciation age of 10.8 ± 0.3 ka (Stroeven et al., 2016). Replicate measurements of sample BG21-002 closely agree, and an age based on a weighted mean 14C concentration is shown in Fig. 4.

The in situ 14C bedrock exposure ages from the Forsmark–Uppland transect (i.e. below the highest postglacial shoreline) consistently increase with elevation and overlap the expected exposure age curve, within uncertainty (Fig. 3). This study adds to the few previous applications of cosmogenic nuclides to defining postglacial landscape emergence above sea level (Briner et al., 2006; Bierman et al., 2018). Briner et al. (2006) present good (visual) congruence with a record of shoreline emergence built from radiocarbon-dated driftwood and fauna by Dyke et al. (1992) using 10Be measurements in boulders on beaches derived from wave-washed till. Their study also mentions that building a relative sea level curve from pebbles, cobbles, and plucked bedrock suffered from inheritance problems, an experience shared by Matmon et al. (2003) while attempting the dating of chert on beach ridges in southern Israel and heeded by Bierman et al. (2018). Bierman et al. (2018) successfully dated landscape emergence on Greenland using 10Be across a range of settings, including bedrock below the highest shoreline, cobbles from beach ridges at the highest shoreline, and boulders and bedrock above the highest shoreline. They note that success hinges on the requirement of warm-based ice and deep glacial erosion in exposing bedrock devoid of an inherited cosmogenic nuclide inventory. In many regions, however, including east-central Sweden and more widely in Fennoscandia, these conditions are not met either because of cold-based conditions (Patton et al., 2016; Stroeven et al., 2016) or because of weakly erosive warm-based ice, such as at Forsmark (Hall et al., 2019; SKB, 2020), during all or much of glacial time. Cosmogenic nuclide inheritance is therefore a part of the landscape fabric. Bierman et al. (2018) advocate the use of in situ 14C as a methodology to circumvent inheritance problems. Our study is the first to follow up on that suggestion and shows, convincingly, that using in situ 14C can extend the study of landscape rebound to regions where ice sheet erosion was insufficiently deep to allow for the application of long-lived nuclides.

Five bedrock samples from above the highest postglacial shoreline are well-clustered, and the weighted mean age (and full uncertainty) of 11.9 ± 1.5 ka overlaps with the predicted deglaciation age of 10.8 ± 0.3 ka (Fig. 4; Hughes et al., 2016; Stroeven et al., 2016). Because derived exposure ages overlap with the predicted deglaciation age, we further infer that the in situ 14C samples, including those located below the highest postglacial shoreline, within uncertainty, lack significant inheritance from previous exposure. Model scenarios of in situ 14C concentration evolution over varying durations of MIS2 and MIS4 ice cover are consistent with minor inheritance, even with short periods of ice coverage and no glacial or interglacial erosion (Fig. 5). Even if the last ice sheet had advanced over the region as late as 28 ka, there would only be a negligible inventory of inherited 14C atoms produced prior to the MIS2 ice advance.

Our in situ 14C data from above the highest (postglacial) shoreline demonstrate their potential for constraining the deglaciation chronology of former ice sheets. This is especially true for regions with thin till drapes, abundant bedrock exposures, and sparse moraines outlining successive retreat stages. In Fennoscandia, thin tills commonly occur (cf. Kleman et al., 2008), and ice sheet retreat appears to have proceeded uninterrupted inside the Younger Dryas moraine belt (apart from the Central Finland Ice Marginal Formation; e.g. Rainio et al., 1986; Stroeven et al., 2016). Even though the post-Younger Dryas deglaciation of east-central Sweden is well-constrained by a clay varve chronology below the highest postglacial shoreline (Strömberg, 1989), there are vast areas above the highest shoreline that remain poorly constrained by data (Stroeven et al., 2016). In addition to a lack of datable deglacial landforms, this is attributable to glacial erosion of bedrock having frequently been insufficient to remove inventories of long half-life 10Be and 26Al (Patton et al., 2022), thereby leaving nuclides inherited from exposure prior to the last glaciation (Heyman et al., 2011; Stroeven et al., 2016). Because of the short 14C half-life and an improved sampling methodology, in situ 14C may now be a prime candidate nuclide to be included in last deglaciation studies on glaciated cratons, such as the dating of boulders deposited along glacial flowlines. This is a technique practised successfully using 10Be (Margold et al., 2019; Norris et al., 2022).

A total of 10 in situ 14C measurements of bedrock are consistent with a RSL curve for Forsmark derived from organic radiocarbon dating of basal sediments in isolation basins and the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet deglaciation chronologies from Stroeven et al. (2016) and Hughes et al. (2016). This study introduces the use of in situ 14C in Fennoscandian Ice Sheet paleoglaciology and outlines a promise of its use as a basis for supporting future shoreline displacement studies and for tracking the deglaciation in areas that lack datable organic material and where 10Be and 26Al routinely return complex exposure results.

Data are available in the Supplement (files S1–S3). Lidar data used in the study are available from https://www.lantmateriet.se (Lantmäteriet, 2020).

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-6-291-2024-supplement.

BWG and APS initiated the study, with support from KH and JON, and drafted the manuscript. BWG, APS, and AL did the sampling. AL performed the petrological analyses of the sampled bedrock. NAL completed the sample preparation for AMS and provided the results. JH carried out cosmogenic nuclide production rate and exposure age calculations. MWC oversaw the AMS. All authors revised the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank Johan Liakka (SKB) for his support in completing this study and Nicolás Young, the anonymous reviewer, and Peiter Vermeesch (editor) for comments that improved this paper.

This research was supported by the Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Company (grant no. 4501759571).

This paper was edited by Pieter Vermeesch and reviewed by Nicolas Young and one anonymous referee.

Alexanderson, H., Hättestrand, M., Lindqvist, M. A., and Sigfusdottir, T.: MIS 3 age of the Veiki moraine in N Sweden – Dating the landform record of an intermediate-sized ice sheet in Scandinavia, Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res., 54, 239–261, 2022.

Balco, G., Stone, J. O., Lifton, N. A., and Dunai, T. J.: A complete and easily accessible means of calculating surface exposure ages or erosion rates from 10Be and 26Al measurements, Quat. Geochronol., 3, 174–195, 2008.

Berglund, M.: The Holocene shore displacement of Gästrikland, eastern Sweden: a contribution to the knowledge of Scandinavian glacio-isostatic uplift, J. Quaternary Sci., 20, 519–531, 2005.

Bergström, E.: Late Holocene distribution of lake sediment and peat in NE Uppland, Sweden, SKB R-01-12, Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, ISSN 1402-3091, 2001.

Bierman, P. R., Rood, D. H., Shakun, J. D., Portenga, E. W., and Corbett, L. B.: Directly dating postglacial Greenlandic land-surface emergence at high resolution using in situ 10Be, Quaternary Res., 90, 110–126, 2018.

Blake Jr., W.: Holocene emergence along the Ellesmere Island coast of northernmost Baffin Bay, Norsk Geol. Tidsskr., 73, 147–160, 1993.

Borchers, B., Marrero, S., Balco, G., Caffee, M., Goehring, B., Lifton, N., Nishiizumi, K., Phillips, F., Schaefer, J., and Stone, J.: Geological calibration of spallation production rates in the CRONUSEarth project, Quat. Geochronol., 31, 188–198, 2016.

Bradwell, T., Fabel, D., Clark, C. D., Chiverrell, R. C., Small, D., Smedley, R. K., Saher, M. H., Moreton, S. G., Dove, D., Callard, S. L., Duller, G. A. T., Medialdea, A., Bateman, M. D., Burke, M. J., McDonald, N., Gilgannon, S., Morgan, S., Roberts, D. H., and Ó Cofaigh, C.: Pattern, style and timing of British-Irish Ice Sheet advance and retreat over the last 45 000 years: evidence from NW Scotland and the adjacent continental shelf, J. Quaternary Sci., 36, 871–933, 2021.

Briner, J. P., Gosse, J. C., and Bierman, P. R.: Applications of cosmogenic nuclides to Laurentide Ice Sheet history and dynamics, Geol. Soc. Am. Spec., 415, 29–41, 2006.

Briner, J. P., Lifton, N. A., Miller, G. H., Refsnider, K., Anderson, R. K., and Finkel, R.: Using in situ cosmogenic 10Be, 14C, and 26Al to decipher the history of polythermal ice sheets, Quat. Geochronol., 19, 4–13, 2014.

Brunnberg, L.: Clay-varve Chronology and Deglaciation during the Younger Dryas and Preboreal in the Easternmost Part of the Middle Swedish Ice Marginal Zone, Department of Quaternary Research, Quaternaria A2, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 1–94, ISBN 91-7153-389-3, 1995.

Dalton, A. S., Margold, M., Stokes, C. R., Tarasov, L., Dyke, A. S., Adams, R. S., Allard, S., Arends, H. E., Atkinson, N., Attig, J. W., Barnett, P. J., Barnett, R. L., Batterson, M., Bernatchez, P., Borns Jr., H. W., Breckenridge, A., Briner, J. P., Brouard, E., Campbell, J. E., Carlson, A. E., Clague, J. J., Curry, B. B., Daigneault, R. A., Dubé-Loubert, H., Easterbrook, D. J., Franzi, D. A., Friedrich, H. G., Funder, S., Gauthier, M. S., Gowan, A. S., Harris, K. L., Hétu, B., Hooyer, T. S., Jennings, C. E., Johnson, M. D., Kehew, A. E., Kelley, S. E., Kerr, D., King, E. L., Kjeldsen, K. K., Knaeble, A. R., Lajeunesse, P., Lakeman, T. R., Lamothe, M., Larson, P., Lavoie, M., Loope, H. M., Lowell, T. V., Lusardi, B. A., Manz, L., McMartin, I., Nixon, F. C., Occhietti, S., Parkhill, M. A., Piper, D. J. W., Pronk, A. G., Richard, P. J. H., Ridge, J. C., Ross, M., Roy, M., Seaman, A., Shaw, J., Stea, R. R., Teller, J. T., Thompson, W. B., Thorleifson, L. H., Utting, D. J., Veillette, J. J., Ward, B. C., Weddle, T. K., and Wright, H. E.: An updated radiocarbon-based ice margin chronology for the last deglaciation of the North American Ice Sheet Complex, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 234, 106223, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106223, 2020.

Dalton, A. S., Dulfer, H. E., Margold, M., Heyman, J., Clague, J. J., Froese, D. G., Gauthier, M. S., Hughes, A. L. C., Jennings, C. E., Norris, S. L., and Stoker, B. J.: Deglaciation of the north American ice sheet complex in calendar years based on a comprehensive database of chronological data: NADI-1, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 321, 108345, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108345, 2023.

De Geer, G.: The transbaltic extension of the Swedish Time Scale, Geogr. Ann., 17, 533–549, 1935.

De Geer, G.: Geochronologia Suecica principles, Kungliga svenska vetenskapsakademien Handlingar, III, Bd 18, 1–367, 1940.

Dyke, A. S., Morris, T. F., Green, D. E. C., and England, J.: Quaternary geology of Prince of Wales Island, Arctic Canada, Geological Survey of Canada, Memoir, 433, 1–142, 1992.

Dyke, A. S., Andrews, J. T., Clark, P. U., England, J. H., Miller, G. H., Shaw, J., and Veillette, J. J.: The Laurentide and Innuitian ice sheets during the Last Glacial Maximum, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 21, 9–31, 2002.

Fogwill, C., Turney, C., Golledge, N., Rood, D., Hippe, K., Wacker, L., and Jones, R.: Drivers of abrupt Holocene shifts in West Antarctic ice stream direction determined from combined ice sheet modelling and geologic signatures, Antarct. Sci., 26, 674–686, 2014.

Goehring, B. M., Schaefer, J. M., Schluechter, C., Lifton, N. A., Finkel, R. C., Jull, A. J. T., Akçar, N., and Alley, R. B.: The Rhone Glacier was smaller than today for most of the Holocene, Geology, 39, 679–682, 2011.

Gosse, J. C. and Phillips, F. M.: Terrestrial in situ cosmogenic nuclides: theory and application, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 20, 1475–1560, 2001.

Greenwood, S. L., Clason, C. C., Nyberg, J., Jakobsson, M., and Holmlund, P.: The Bothnian Sea ice stream: early Holocene retreat dynamics of the south-central Fennoscandian Ice Sheet, Boreas, 46, 346–362, 2017.

Greenwood, S. L., Simkins, L. M., Winsborrow, M. C. M., and Bjarnadottir, L. R.: Exceptions to bed-controlled ice sheet flow and retreat from glaciated continental margins worldwide, Sci. Adv., 7, eabb6291, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb6291, 2021.

Hall A. M., Ebert K., Goodfellow B. W., Hättestrand C., Heyman J., Krabbendam M., Moon S., and Stroeven A. P.: Past and future impact of glacial erosion in Forsmark and Uppland, TR-19-07 Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, ISSN 1404-0344, 2019.

Hall, A. M., Krabbendam, M., van Boeckel, M., Goodfellow, B. W., Hättestrand, C., Heyman, J., Palamakumbura, R. N., Stroeven A. P., and Näslund, J.-O.: Glacial ripping: geomorphological evidence from Sweden for a new process of glacial erosion, Geogr. Ann., 102, 333–353, 2020.

Hedenström, A. and Risberg, J.: Shore displacement in northern Uppland during the last 6500 calender years, TR-03-17 Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, ISSN 1404-0344, 2003.

Heyman, J.: Expage calculator, version 202403, GitHub [code], http://expage.github.io/calculator (last access: 31 March 2024), 2024.

Heyman, J., Stroeven, A. P., Harbor, J. M., and Caffee, M. W.: Too young or too old: Evaluating cosmogenic exposure dating based on an analysis of compiled boulder exposure ages, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 302, 71–80, 2011.

Hippe, K. and Lifton, N. A.: Calculating isotope ratios and nuclide concentrations for in situ cosmogenic 14C Analyses, Radiocarbon, 56, 1167–1174, 2014.

Hippe, K., Ivy-Ochs, S., Kober, F., Zasadni, J., Wieler, R., Wacker, L., Kubik, P. W., and Schlüchter, C.: Chronology of Lateglacial ice flow reorganization and deglaciation in the Gotthard Pass area, Central Swiss Alps, based on cosmogenic 10Be and in situ 14C, Quat. Geochronol., 19, 14–26, 2014.

Hughes, A. L. C., Gyllencreutz, R., Lohne, Ø. S., Mangerud, J., and Svendsen, J. I.: The last Eurasian ice sheets – a chronological database and time-slice reconstruction, DATED-1, Boreas, 45, 1–45, 2016.

Ivy-Ochs, S. and Kober, F.: Surface exposure dating with cosmogenic nuclides, Quaternary Sci. J., 57, 157–189, 2008.

Kleman, J., Stroeven, A. P., and Lundqvist, J.: Patterns of Quaternary ice sheet erosion and deposition in Fennoscandia and a theoretical framework for explanation, Geomorphology, 97, 73–90, 2008.

Kleman, J., Hättestrand, M., Borgström, I., Preusser, F., and Fabel, D.: The Idre marginal moraine–an anchorpoint for Middle and Late Weichselian ice sheet chronology, Quaternary Sci. Adv., 2, 100010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qsa.2020.100010, 2020.

Koester, A. J. and Lifton, N. A.: Technical note: A software framework for calculating compositionally dependent in situ 14C production rates, Geochronology, 5, 21–33, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-5-21-2023, 2023.

Koester, A. J. and Lifton, N. A.: Corrigendum to “Technical note: A software framework for calculating compositionally dependent in situ 14C production rates” published in Geochronology, 5, 21–33, 2023, Corrigendum to Geochronology, 5, 21–33, 2023, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-5-21-2023-corrigendum, 2024.

Lal, D.: Cosmic ray labeling of erosion surfaces: in situ nuclide production rates and erosion rates, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 104, 424–439, 1991.

Lambeck, K., Smither, C., and Johnston, P.: Sea-level change, glacial rebound and mantle viscosity for northern Europe, Geophys. J. Int., 134, 102–134, 1998.

Lambeck, K., Purcell, A., Zhao, J., and Svensson, N.-O.: The Scandinavian Ice Sheet: from MIS 4 to the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, Boreas, 39, 410–435, 2010.

Lantmäteriet: Produktbeskrivning: GSD-Höjddata, Grid 2+, https://www.lantmateriet.se (last access: 1 June 2023), 2020.

Lidberg, M., Johansson, J. M., Scherneck, H.-G., and Milne, G. A.: Recent results based on continuous GPS observations of the GIA process in Fennoscandia from BIFROST, J. Geodyn., 50, 8–18, 2010.

Lifton, N.: Implications of two Holocene time-dependent geomagnetic models for cosmogenic nuclide production rate scaling, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 433, 257–268, 2016.

Lifton, N., Sato, T., and Dunai, T. J.: Scaling in situ cosmogenic nuclide production rates using analytical approximations to atmospheric cosmic-ray fluxes, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 386, 149–160, 2014.

Lifton, N., Caffee, M., Finkel, R., Marrero, S., Nishiizumi, K., Phillips, F. M., Goehring, B., Gosse, J., Stone, J., Schaefer, J., and Theriault, B.: In situ cosmogenic nuclide production rate calibration for the CRONUS-Earth project from Lake Bonneville, Utah, shoreline features, Quat. Geochronol., 26, 56–69, 2015.

Lifton, N., Wilson, J., and Koester, A.: Technical note: Studying lithium metaborate fluxes and extraction protocols with a new, fully automated in situ cosmogenic 14C processing system at PRIME Lab, Geochronology, 5, 361–375, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-5-361-2023, 2023.

Long, A. J., Woodroffe, S. A., Roberts, D. H., and Dawson, S.: Isolation basins, sea-level changes and the Holocene history of the Greenland Ice Sheet, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 30, 3748–3768, 2011.

Lönnqvist, M. and Hökmark, H.: Approach to estimating the maximum depth for glacially induced hydraulic jacking in fractured crystalline rock at Forsmark, Sweden, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth, 118, 1777–1791, 2013.

Lupker, M., Hippe, K., Wacker, L., Kober, F., Maden, C., Braucher, R., Bourlès, D., Romani, J. R. V., and Wieler, R.: Depth-dependence of the production rate of in situ 14C in quartz from the Leymon High core, Spain, Quat. Geochronol., 28, 80–87, 2015.

Margold, M., Gosse, J. C., Hidy, A. J., Woywitka, R. J., Young, J. M., and Froese, D.: Beryllium-10 dating of the Foothills Erratics Train in Alberta, Canada, indicates detachment of the Laurentide Ice Sheet from the Rocky Mountains at ∼ 15 ka, Quaternary Research, 92, 469–482, 2019.

Marrero, S. M., Phillips, F. M., Caffee, M. W., and Gosse, J. C.: CRONUS-Earth cosmogenic 36Cl calibration, Quat. Geochronol., 31, 199–219, 2016.

Matmon, A., Crouvi, O., Enzel, Y., Bierman, P., Larsen, J., Porat, N., Amit, R., and Caffee, M.: Complex exposure histories of chert clasts in the late Pleistocene shorelines of Lake Lisan, southern Israel, Earth Surf. Proc. Land., 28, 493–506, 2003.

Miller, G. H., Briner, J. P., Lifton, N. A., and Finkel, R. C.: Limited ice-sheet erosion and complex exposure histories derived from in situ cosmogenic 10Be, 26Al, 14C on Baffin Island, Arctic Canada, Quat. Geochronol., 1, 74–85, 2006.

Moon, S., Perron, J. T., Martel, S. J., Goodfellow, B. W., Mas Ivars, D., Hall, A., Heyman, J., Munier, R., Näslund, J.-O., Simeonov, A., and Stroeven, A. P.: Present-day stress field influences bedrock fracture openness deep into the subsurface, Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2020GL090581, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL090581, 2020.

Norris, S. L., Tarasov, L., Monteath, A. J., Gosse, J. C., Hidy, A. J., Margold, M., and Froese, D. G.: Rapid retreat of the southwestern Laurentide Ice Sheet during the Bølling-Allerød interval, Geology, 50, 417–421, 2022.

Påsse, T. and Andersson, L: Shore-level displacement in Fennoscandia calculated from empirical data, GFF, 127, 253–268, 2005.

Patton, H., Hubbard, A., Andreassen, K., Winsborrow, M., and Stroeven, A. P.: The build-up, configuration, and dynamical sensitivity of the Eurasian ice-sheet complex to Late Weichselian climatic and oceanic forcing, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 153, 97–121, 2016.

Patton, H., Hubbard, A., Andreassen, K., Auriac, A., Whitehouse, P. L., Stroeven, A. P., Shackleton, C., Winsborrow, M., Heyman, J., and Hall, A. M.: Deglaciation of the Eurasian ice sheet complex, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 169, 148–172, 2017.

Patton, H., Hubbard, A., Heyman, J., Alexandropoulou, N., Lasabuda, A. P. E., Stroeven, A. P., Hall, A. M., Winsborrow, M., Sugden, D. E., Kleman, J., and Andreassen, K.: The extreme yet transient nature of glacial erosion, Nat. Commun., 13, 7377, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-35072-0, 2022.

Pendleton, S., Miller, G., Lifton, N., and Young, N.: Cryosphere response resolves conflicting evidence for the timing of peak Holocene warmth on Baffin Island, Arctic Canada, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 216, 107–115, 2019.

Phillips, F. M., Argento, D. C., Balco, G., Caffee, M. W., Clem, J., Dunai, T. J., Finkel, R., Goehring, B., Gosse, J. C., Hudson, A. M., Jull, A. J. T., Kelly, M. A., Kurz, M., Lal, D., Lifton, N., Marrero, S. M., Nishiizumi, K., Reedy, R. C., Schaefer, J., Stone, J. O. H., Swanson, T., and Zreda, M. G.: The CRONUS-Earth Project: A synthesis, Quat. Geochronol., 31, 119–154, 2016.

Rainio, H., Kejonen, A., Kielosto, S., and Lahermo, P.: Avancerade inlandsisen på nytt också till Mellanfinska randformationen?, Geologi, 38, 95–109, 1986.

Regnéll, C., Becher, G. P., Öhrling, C., Greenwood, S. L., Gyllencreutz, R., Blomdin, R., Brendryen, J., Goodfellow, B. W., Mikko, H., Ransed, G., and Smith, C.: Ice-dammed lakes and deglaciation history of the Scandinavian Ice Sheet in central Jämtland, Sweden, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 314, 108219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108219, 2023.

Risberg, J.: Strandförskjutningen i nordvästra Uppland under subboreal tid. In Segerberg, A. Bälinge mossar: kustbor i Uppland under yngre stenålder, PhD Thesis, Uppsala University, Appendix 4, ISBN 91-506-1385-5, 1999 (in Swedish).

Robertsson, A.-M. and Persson, C.: Biostratigraphical studies of three mires in northern Uppland, Sweden, Sveriges geologiska undersökning, Serie C 821, ISSN 0082-0024, 1989.

Romundset, A., Bondevik, S., and Bennike, O.: Postglacial uplift and relative sea level changes in Finnmark, northern Norway, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 30, 2398–2421, 2011.

Schildgen, T. F., Phillips, W. M., and Purves, R. S.: Simulation of snow shielding corrections for cosmogenic nuclide surface exposure studies, Geomorphology, 64, 67–85, 2005.

Schimmelpfennig, I., Schaefer, J. M., Goehring, B. M., Lifton, N., Putnam, A. E., and Barrell, D. J.: Calibration of the in situ cosmogenic 14C production rate in New Zealand's Southern Alps, J. Quaternary Sci., 27, 671–674, 2012.

Schimmelpfennig, I., Schaefer, J. M., Lamp, J., Godard, V., Schwartz, R., Bard, E., Tuna, T., Akçar, N., Schlüchter, C., Zimmerman, S., and ASTER Team: Glacier response to Holocene warmth inferred from in situ 10Be and 14C bedrock analyses in Steingletscher's forefield (central Swiss Alps), Clim. Past, 18, 23–44, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-18-23-2022, 2022.

Schweinsberg, A. D., Briner, J. P., Miller, G. H., Lifton, N. A., Bennike, O., and Graham, B. L.: Holocene mountain glacier history in the Sukkertoppen Iskappe area, southwest Greenland, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 197, 142–161, 2018.

SGU: Högsta Kustlinjen, Geological Survey of Sweden, https://resource.sgu.se/dokument/produkter/hogsta-kustlinjen-beskrivning (last access: 19 June 2024), 2015 (in Swedish).

Simkins, L. M., Simms, A. R., and DeWitt, R.: Relative sea-level history of Marguerite Bay, Antarctic Peninsula derived from optically stimulated luminescence-dated beach cobbles, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 77, 141–155, 2013.

SKB: Post-closure safety for the final repository for spent nuclear fuel at Forsmark – Climate and climate-related issues, PSAR version, TR-20-12, Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, ISSN 1404-0344, 2020.

SKB: Post-closure safety for the final repository for spent nuclear fuel at Forsmark – Main report, PSAR version, SKB TR-21-01, Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB, ISSN 1404-0344, 2022.

Steffen, H. and Wu, P.: Glacial isostatic adjustment in Fennoscandia – A review of data and modeling, J. Geodynam., 52, 169–204, 2011.

Steinemann, O., Ivy-Ochs, S., Hippe, K., Christl, M., Haghipour, N., and Synal, H. A.: Glacial erosion by the Trift glacier (Switzerland): Deciphering the development of riegels, rock basins and gorges, Geomorphology, 375, 107533, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107533, 2021.

Stephens, M. B. and Jansson, N. F.: Chap. 6, Paleoproterozoic (1.9–1.8 Ga) syn-orogenic magmatism, sedimentation and mineralization in the Bergslagen lithotectonic unit, Svecokarelian orogen, in: Sweden: Lithotectonic Framework, Tectonic Evolution and Mineral Resources, edited by: Stephens, M. B. and Bergman Weihed, J., Geological Society of London Memoirs, 50, 105–206, https://doi.org/10.1144/M50-2017-40, 2020.

Stroeven, A. P., Heyman, J., Fabel, D., Björck, S., Caffee, M. W., Fredin, O., and Harbor, J. M.: A new Scandinavian reference 10Be production rate, Quat. Geochronol., 29, 104–115, 2015.

Stroeven, A. P., Hättestrand, C., Kleman, J., Heyman, J., Fabel, D., Fredin, O., Goodfellow, B. W., Harbor, J. M., Jansen, J. D., Olsen, L., Caffee, M. W., Fink, D., Lundqvist, J., Rosqvist, G. C., Strömberg, B., and Jansson, K. N.: Deglaciation of Fennoscandia, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 147, 91–12, 2016.

Strömberg, B.: Late Weichselian deglaciation and clay varve chronology in east-central Sweden, Sveriges geologiska undersökning (Ser. Ca 73), ISSN 0348-1352, 1989.

Strömberg, B.: Younger Dryas deglaciation at Mt. Billingen, and clay varve dating of the Younger Dryas/Preboreal transition, Boreas, 23, 177–193, 1994.

Wohlfarth, B., Björck, S., and Possnert, G.: The Swedish Time Scale: a potential calibration tool for the radiocarbon time scale during the late Weichselian, Radiocarbon, 37, 347–359, 1995.

Young, N. E., Schaefer, J. M., Goehring, B., Lifton, N., Schimmelpfennig, I., and Briner, J. P.: West Greenland and global in situ 14C production-rate calibrations, J. Quaternary Sci., 29, 401–406, 2014.

Young, N. E., Lesnek, A. J., Cuzzone, J. K., Briner, J. P., Badgeley, J. A., Balter-Kennedy, A., Graham, B. L., Cluett, A., Lamp, J. L., Schwartz, R., Tuna, T., Bard, E., Caffee, M. W., Zimmerman, S. R. H., and Schaefer, J. M.: In situ cosmogenic 10Be–14C–26Al measurements from recently deglaciated bedrock as a new tool to decipher changes in Greenland Ice Sheet size, Clim. Past, 17, 419–450, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-17-419-2021, 2021.