the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Effect of chemical abrasion of zircon on SIMS U–Pb, δ18O, trace element, and LA-ICPMS trace element and Lu–Hf isotopic analyses

Cate Kooymans

Charles W. Magee Jr.

Kathryn Waltenberg

Noreen J. Evans

Simon Bodorkos

Yuri Amelin

Sandra L. Kamo

Trevor Ireland

This study assesses the effect of chemical abrasion on in situ mass spectrometric isotopic and elemental analyses in zircon. Chemical abrasion improves the U–Pb systematics of SIMS (secondary ion mass spectrometry) analyses of reference zircons, while leaving other isotopic systems largely unchanged. SIMS ages of chemically abraded reference materials TEMORA-2, 91500, QGNG, and OG1 are precise to within 0.25 % to 0.4 % and are within uncertainty of chemically abraded TIMS (thermal ionization mass spectrometry) reference ages, while SIMS ages of untreated zircons are within uncertainty of TIMS reference ages where chemical abrasion was not used. Chemically abraded and untreated zircons appear to cross-calibrate within uncertainty using all but one possible permutation of reference materials, provided that the corresponding chemically abraded or untreated reference age is used for the appropriate material. In the case of reference zircons QGNG and OG1, which are slightly discordant, the SIMS U–Pb ages of chemically abraded and untreated material differ beyond their respective 95 % confidence intervals.

SIMS U–Pb analysis of chemically abraded zircon with multiple growth stages is more difficult to interpret. Treated igneous rims on zircon crystals from the S-type Mount Painter Volcanics are much lower in common Pb than the rims on untreated zircon grains. However, the analyses of chemically abraded material show excess scatter. Chemical abrasion also changes the relative abundance of the ages of zircon cores inherited from the sedimentary protolith, presumably due to some populations being more likely to survive the chemical abrasion process than others. We consider these results from inherited S-type zircon cores to be indicative of results for detrital zircon grains from unmelted sediments.

Trace element, δ18O, and εHf analyses were also performed on these zircons. None of these systems showed substantial changes as a result of chemical abrasion. The most discordant reference material, OG1, showed a loss of OH as a result of chemical abrasion, presumably due to dissolution of hydrous metamict domains or thermal dehydration during the annealing step of chemical abrasion. In no case did zircon gain fluorine due to exchange of lattice-bound substituted OH or other anions with fluorine during the HF partial dissolution phase of the chemical abrasion process. As the OG1, QGNG, and TEMORA-2 zircon samples are known to be compositionally inhomogeneous in trace element composition, spot-to-spot differences dominated the trace element results. Even the 91500 megacrystic zircon pieces exhibited substantial chip-to-chip variation. The light rare earth elements (LREEs) in chemically abraded OG1 and TEMORA-2 were lower than in the untreated samples. Ti concentration and phosphorus saturation ((Y + REE) P) were generally unchanged in all samples.

- Article

(8557 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(8711 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Three lines of development have driven the evolution of zircon U–Pb geochronology from its inception (Holmes, 1913) to the present day. The first is improving the precision and accuracy of Pb isotopic composition and U–Pb ratio measurements. The second is developing sample treatments that allow extraction and analysis of domains in the zircon crystals that were closed to migration of U and radiogenic Pb. The third is better understanding the sources and formation conditions of the zircons and their host rocks through analysis of zircon trace elemental, radiogenic, and stable isotopic compositions.

Among the developments that help analyze closed U–Pb systems, chemical abrasion (Mattinson, 2005; Mundil et al., 2004) is arguably the most important. This, together with preparation of large quantities of carefully calibrated isotopic tracers in the EARTHTIME initiative (Condon et al., 2015; McLean et al., 2015), raised the analytical precision and accuracy of U–Pb dating to a new level. At the same time, the measurement of multiple isotopic systems in individual zircon grains, in particular SIMS (secondary ion mass spectrometry) stable oxygen isotopes (Schuhmacher et al., 2004; Ickert et al., 2008) and the Lu–Hf system by both solution and laser ablation MC-ICPMS (multicollector–inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry) techniques (Amelin et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 2005; Hiess et al., 2009), has built geologic context around the U–Pb age in terms of constraining the source material and crustal history of the melt from which the zircon crystallized. As these latter multiple isotopic system techniques involve in situ microbeam techniques and chemical abrasion is usually used on dissolved samples, the applicability of microbeam techniques to chemically abraded samples should be further studied.

The first question is whether or not reference ages determined using CA-ID-TIMS (chemical abrasion–isotope dilution TIMS) are suitable for untreated reference zircons during SIMS analysis. ID-TIMS analyses of reference zircons QGNG (Black et al., 2003) and OG1 (Stern et al., 2009) show that for both of these zircon samples the date is about half a percent younger than the age. The use of chemical abrasion rectifies this level of Pb loss (Schoene et al., 2006; Stern et al., 2009). The original studies suggested that the discordant date of the original studies was closest to the dates determined by SIMS. Magee et al. (2023) also show that 14 sessions of OG1 data from the Geoscience Australia SHRIMP (Sensitive High-Resolution Ion Microprobe – a type of SIMS instrument) geochronology laboratory have OG1 dates closer to the 3440.7±3.2 Ma (Stern et al., 2009) U–Pb date for untreated OG1 zircon than the 3463.7±3.6 Ma date (Stern et al., 2009) for chemically abraded OG1. But this is a relatively small proportion of the data available in public databases.

The in situ analysis of chemically abraded material is also understudied. Laser ICPMS studies (e.g., Crowley et al., 2014) have shown that chemical abrasion can introduce matrix effects which cause apparent U–Pb age offsets of up to several percent, but Donaghy et al. (2024) demonstrate that reference-unknown matching can reduce this effect. In contrast, SIMS studies have shown no appreciable effect for young zircons with low radiation damage (Watts et al., 2016), but results from zircons with more extensive radiation damage are consistent with the chemical abrasion process ameliorating Pb loss (Kryza et al., 2012, 2014; Vogt et al., 2023).

In addition to U–Pb data, Vogt et al. (2023) also measure trace elements and oxygen isotopes in both chemically abraded and untreated zircon from the S-type Cambrian Rumburk granite (German–Czech border). They show that ratios are higher in chemically abraded zircon and that δ18O values have a similar mean to untreated zircon but are less scattered. The Vogt et al. (2023) data are consistent with solution trace element data from McKanna et al. (2024), who show that incompatible light rare earth elements (LREEs) are lower in chemically abraded zircon, having been preferentially leached from zircon during the partial dissolution phase of chemical abrasion.

Although these studies are excellent, SIMS chemical abrasion studies in the literature are often used on samples thought to be tricky to analyze due to potential Pb mobility (Kryza et al., 2012, 2014; Vogt et al., 2023). Only Watts et al. (2016) also used SIMS on chemically abraded reference zircon, and there are no published data for SIMS analysis of chemically abraded Precambrian zircons (aside form a few inherited cores in Vogt et al., 2023). In this study, we take four well-known and widely used reference zircons spanning the timescale from the Devonian to Paleoarchean and compare how chemically abraded material performs against untreated material during U–Pb, oxygen isotope, and trace elemental analysis by SIMS and U–Pb, Lu–Hf, and trace element analysis by laser ablation. In addition to reference zircons, we analyze a population of zircons with distinct rims and cores from an S-type volcanic rock to evaluate the effect of chemical abrasion on zircons with multiple growth domains. Multi-age zircon is often targeted with microbeam techniques and is relatively understudied by CA-ID-TIMS relative to simple igneous zircon due to issues related to mixing domains during dissolution.

In this study of U–Pb systematics of zircon, we mainly focus mainly on the isotopic system in preference to the system. In nearly concordant zircons with a small degree of recent Pb loss and no ancient Pb loss, the ratio is almost constant. SIMS Pb isotopic fractionation is covered in Stern et al. (2009). Kositcin et al. (2011) show that this SHRIMP laboratory can produce ages with 2 ‰ precision, which correctly identify zircon grain subzones with ∼1 % difference in age (e.g., the Illogwa Shear Zone mylonite in Kositcin et al., 2011). As a result, we report ages for reference materials of Paleoproterozoic and Paleoarchean age, where the system is usually used when trying to date unknowns instead of illustrate processes.

Samples

Four reference zircons and one local igneous zircon were used in this study. The reference zircons were chosen to be old enough for precision not to be limited by counting statistics and different enough in age to span most of the timescale in which the Geoscience Australia SHRIMP laboratory works. They were TEMORA-2 (Black et al., 2004), 91500 (Wiedenbeck et al., 1995), QGNG (Black et al., 2003), and OG1 (Stern et al., 2009). For this paper, the untreated versions of these four reference zircons are T2U, 91U, QNU, and OGU, respectively, while the chemically abraded material is T2C, 91C, QNC, and OGC.

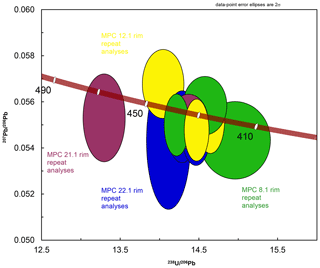

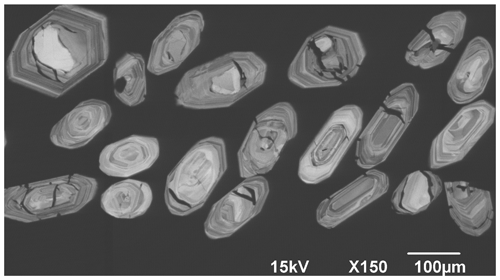

Figure 1CL image of chemically abraded Mount Painter Volcanics S-type dacitic zircon grains, showing etch channels from the partial HF dissolution. Many of these channels at least partially follow the core–rim boundary in those grains with both visible etch channels and inherited cores exposed at the level of the polishing plane. Complete transmitted, reflected, and CL maps of all samples are in Figs. S1 and S2.

Zircon from the S-type dacitic from the Mount Painter Volcanics (Abell, 1991) was also chosen. The Mount Painter Volcanics are part of the late Silurian volcano-sedimentary package that underlies the city of Canberra, Australia, and is part of the Lachlan Orogen. S-type igneous zircons in SE Australia often have igneous rims overgrowing older sedimentary cores, so the use of this zircon allowed us to investigate the effect of chemical abrasion on zircon with multiple growth domains (Fig. 1). This particular sample was chosen because the rims are fairly large (generally 25–75 µm) and easy to target with microbeam techniques. These volcanic zircon rims are also lower in U content than equivalent granite rims, which often go metamict, and may not survive the chemical abrasion process. The untreated and chemically abraded material for this sample is referred to as MPU and MPC.

2.1 Database search

In order to further test the mean date of untreated OG1 as determined by SHRIMP, we decided to interrogate every OG1 spot analysis in the Geoscience Australia database. This spot-by-spot U–Pb SHRIMP data from OG1 correspond to the full set of analyses made in support of data publicly released by Geoscience Australia since OG1 was introduced in 2007. As OG1 is our primary reference material for monitoring Pb isotopic fractionation, it has been run in almost every session since it was introduced. The data can be accessed at the Geoscience Australia portal (Fraser et al., 2020) (https://portal.ga.gov.au/persona/geochronology, last access: 6 March 2024) in Map Layer “Geochronology and Isotopes”, sublayer “Geochronology Data – Sensitive High-Resolution Ion Microprobe (SHRIMP) Analyses”. Within this sublayer, the full dataset (all SHRIMP spots, not just OG1) can be accessed in the “About” subtab, where the Download button gives a CSV option. We downloaded the CSV file (∼240 MB) on 6 March 2024 and filtered the output to GA_SampleID = “OG1” (i.e., GA_SampleNo = 2 129 532). All OG1 dates were determined using TEMORA-2 as the primary reference zircon and the Black et al. (2004) reference value. OG1-related data from several analytical sessions (SHRIMP_SessionNos 80108, 80140, 90058, 100111, 140034, 140039, and 160009) have been uploaded twice to accommodate different iterations of data reduction applied to the associated unknowns, and each set of duplicate OG1 analyses has been removed from the overall OG1 dataset to ensure that each of the remaining spot analyses represents a unique combination of SIMS instrument (all of which are SHRIMP instruments located in Australia) and analytical date and time. The filtered dataset (n=10 619) is used to calculate and dates. Columns used to assess 204Pb-corrected dates are C4_PB206_U238_AGE_MA and C4_PB206_U238_ AGE_ 1SIGMA_MA. Columns used for 204Pb-corrected dates are C4_PB207_PB206_AGE_MA and C4_PB207_PB206_AGE_1SIGMA_MA. Weighted means, robust (Tukey's biweight) means, and medians were calculated using Isoplot3.71 (Ludwig, 2003).

2.2 Reference materials and values

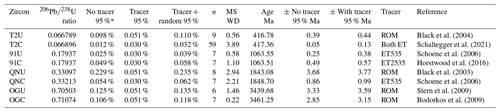

To evaluate the effect of chemical abrasion on SIMS U–Pb analyses, we need to consistently compare our SHRIMP results to ID-TIMS reference ages of both untreated and chemically abraded zircon. This is complicated by the fact that literature ID-TIMS values for these reference zircons span 28 years, during which the methodology of ID-TIMS zircon geochronology has evolved.

Since the widespread adoption of chemical abrasion in the late 2000s, few U–Pb ID-TIMS ages of untreated reference zircons have been published, so reference ages for untreated zircons are generally from papers older than reference ages for chemically abraded zircons. Chemical abrasion improves the precision of TIMS U–Pb analyses, but so do improvements to blanks, tracers, mass spectrometers, and every other aspect of TIMS which occurred between the untreated reference value determinations and the chemically abraded reference value determinations.

One area where TIMS precision has improved over the last few decades is tracer uncertainty. Ideally we would use reference ages for all four reference zircons in both the chemically abraded and untreated state, determined using a single tracer. However, such a study has not yet been published. Instead, we chose reference ages calculated using the minimum number of different tracers for which we could find information.

There are three isotopic tracers used in our choice of reference values. They are (with samples used) the following.

-

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) tracer (T2U, QNU, OGU, OGC); Black et al. (2003, 2004), Stern et al. (2009), Bodorkos et al. (2009)

-

EARTHTIME 535 tracer (91U, QNC, T2C); Schoene et al. (2006), Schaltegger et al. (2021)

-

EARTHTIME 2535 tracer (91C, T2C); Horstwood et al. (2016), Schaltegger et al. (2021)

The two EARTHTIME tracers have identical ratios, which is the key ratio in determination of ages, and are considered to be the same for the purposes of this study, as Schaltegger et al. (2021) show no systematic difference in the age of TEMORA-2.

Using the published uncertainties for these tracers complicates intercomparison of untreated and chemically abraded material because the published uncertainty in the ROM tracer given in Black et al. (2003) is an order of magnitude higher than the EARTHTIME (McLean et al., 2015) tracer uncertainties. This causes the tracer uncertainty for the Black et al. (2003, 2004), Stern et al. (2009), and Bodorkos et al. (2009) results to dominate the total uncertainty budget. Reducing this order-of-magnitude difference in tracer uncertainty makes intercomparison of CA and untreated results more straightforward.

The EARTHTIME project, in addition to creating the EARTHTIME tracer, also involved widely distributing several gravimetric solutions, which can be used to more precisely and accurately determine the isotopic ratios of tracer solutions. We are publishing ROM tracer results determined using all three of the gravimetric solutions described by Condon et al. (2015). These data were acquired after the Black et al. (2003, 2004) data but before the Stern et al. (2009) and Bodorkos et al. (2009) data, making them relevant for the ROM lab at the time these reference values were determined. This allows us to reduce the reference value uncertainty for the (mostly untreated) samples analyzed at the ROM to a level more commensurate with the EARTHTIME tracer and well below SHRIMP analytical uncertainty.

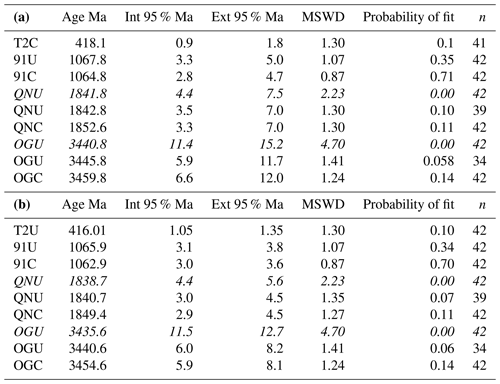

For consistency, we recalculate all reference values using a single methodology. We take the weighted mean of the individual aliquots where available and calculate the analytical uncertainty by multiplying the standard deviation of these results by Student's t. Where the probability of fit is less than 0.05, we also multiply by the square root of the MSWD. We also include the details of those four aliquots for OGC, used in the calculation of the mean value for Bodorkos et al. (2009), but not presented on an individual aliquot basis or published in Stern et al. (2009). For consistency, we apply the same calculation to the ratios from all of the reference analyses, generating the reference values and uncertainties given in Table 1. This difference in methodology accounts for the difference in these Table 1 values and their uncertainties compared to the headline numbers in the source papers.

Table 1Reference values recalculated from the literature using consistent uncertainty treatment and reduced tracer uncertainty from gravimetric solution analyses.

* If the probability of fit <0.05, the 95 % confidence internal is defined as 1 standard deviation × Student's t for the population. For lower probabilities of fit, the 95 %

confidence interval is expanded by a factor of the square root of MSWD.

Reference values derived from analyses using the same isotopic tracer do not need to propagate the tracer uncertainty when being compared to each other; similarly, the isotopic tracer uncertainty portion of the reference value uncertainty does not need to be propagated within SHRIMP sessions comparing two zircon reference values derived from the same tracer.

SHRIMP uncertainty propagation is described in Magee et al. (2023); in short, SHRIMP results in a single session can be compared to each other using just the sample analytical uncertainties (internal errors of Stern and Amelin, 2003). However, when SHRIMP dates are compared to a TIMS reference value, the uncertainty of the SHRIMP reference zircon measurement for that session needs to be considered, as does the uncertainty in the SHRIMP reference zircon value. However, if a SHRIMP age is being compared to a TIMS reference age which used the same tracer as the reference zircon for the SHRIMP session, the tracer component of the reference zircon uncertainty should not be propagated. So, for example, a SHRIMP session using untreated TEMORA-2 (Black et al., 2004) as the reference zircon would not include the tracer portion of the reference zircon uncertainty when comparing the SHRIMP age for untreated QGNG to the reference TIMS age published in Black et al. (2003), as Black et al. (2003) and Black et al. (2004) both used the same tracer.

FC1 was used as the reference material for oxygen isotopes, with analyses distributed through the analytical session. A reference value of 5.6 ‰ was used (Ávila et al., 2020).

For negative ion multicollector work on SHRIMP SI, the Coble et al. (2018) value of 15 ppm for 91500 was used to standardize fluorine contents of unknown zircon samples. No applicable OH values of any of the zircons studied here could be found, so ratios are presented in raw form for data interpretation.

For positive ions, SHRIMP trace element concentrations were referenced to GZ7 (Nasdala et al., 2018) on our setup mount (GA5040). M127 (Nasdala et al., 2016) analyses from both the setup and experimental mounts, 91500 analyses from both mounts, and GZ8 (Nasdala et al., 2018) from the setup mount were used as secondary reference materials. For elements such as aluminum, which were not listed for GZ7 in Nasdala et al. (2018), the Coble et al. (2018) values for 91500 were used. The Szymanowski et al. (2018) isotope dilution value for titanium in GZ-7 was used for titanium concentrations to minimize the contribution of reference value uncertainty to the total uncertainty budget for titanium concentration determination.

The laser ICP-MS split-stream analyses used a setup mount containing 91500 (Wiedenbeck et al., 1995), Mud Tank (Woodhead and Hergt, 2005), Plešovice (Sláma et al., 2008), OG1 (Stern et al., 2009), and GJ-1 (Jackson et al., 2004) zircons, as well as NIST NBS 610 and 614 glass. Exact values and isotopic ratios used in the peak stripping process are given in the analytical methods below.

2.3 Sample preparation

Chemical abrasion of zircons was done at the Australian National University (ANU) in the manner of Huyskens et al. (2016). Aliquots of OG1, QGNG, 91500, Mount Painter, and TEMORA-2 zircon were chemically abraded by annealing at 900 °C for 48 h. Concentrated HF partially dissolved the annealed zircons at 190 °C for 15 h in a Parr bomb. After rinsing, the zircons returned to the Parr bomb for 15 h at 190 °C in HCl. A few hundred grains of both chemically abraded and unabraded zircons from each sample were then mounted in the center 10 mm × 10 mm region of two 25 mm epoxy disk mounts (mount GA6363: reference zircons, mount GA6364: Mount Painter Volcanics), produced according to the methods of DiBugnara (2016). After mount preparation and polishing, GA6363 and GA6364 were imaged in transmitted light, reflected light, and cathodoluminescence before being sputter-cleaned with argon and sputter-coated with 15 nm of gold for surface conductivity during analysis.

2.4 Analytical campaign

The analytical campaign involved making and photographing the mounts, performing U–Pb SHRIMP analyses in the Geoscience Australia geochronology laboratory, repolishing the spots off to prevent implanted 16O from compromising the next experiment, and analyzing for δ18O, OH, and F on SHRIMP SI at the Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University. After a preliminary analysis of the results, a subset of the previous spots was analyzed for trace elements by SHRIMP IIe at Geoscience Australia. Afterwards, mount GA6363 was taken to Curtin University for laser ablation split-stream (LASS) trace element + Hf isotopic analysis. Due to the greater thickness of zircon grains needed for LASS analyses (tens of micrometers instead of 1 µm), many of the laser analyses had to be relocated from where the SHRIMP spots were placed. Laser ablation analyses were not attempted on the Mount Painter Volcanics S-type zircons (mount GA6364) due to the possibility of rim–core drill-throughs complicating the interpretation.

During the data analysis, it was discovered that the initial SHRIMP trace element data for mount GA6363 were unsuitable due to a misplaced praseodymium peak. The laser holes were filled with epoxy, the mount was repolished, and both mounts were reanalyzed for trace elements on the Geoscience Australia SHRIMP IIe. All spot locations, as well as full transmitted, reflected light, and CL images, are included as Figs. S1 (mount GA6363) and S2 (mount GA6364) in the Supplement.

2.5 Analytical procedures

2.5.1 CA-ID-TIMS

The ID-TIMS analyses reported in Black et al. (2003, 2004) and Stern et al. (2009) were completed at the Jack Satterly Geochronology Laboratory, Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Toronto, Canada, using the ROM tracer solution. As part of the EARTHTIME initiative in 2005, the ROM tracer was recalibrated against three U–Pb gravimetric reference solutions provided by the initiative (“JMM”, “NIGL”, “MIT”, results reported in Table S1 in the Supplement; see Condon et al., 2015). The aim at the time was to improve intercomparability of dates reported by multiple laboratories by standardizing the calibration of each U–Pb ratio for individually prepared tracer solutions.

Zircon grains which did not undergo chemical abrasion were mechanically air-abraded (Krogh, 1982). For the chemically abraded OG1 TIMS results (Mattinson, 2005), zircons were thermally annealed at 1000 °C for 48 h and etched in 50 % hydrofluoric acid at 200 °C for either 12 or 17 h. Results for the chemically abraded OGC grains not included in Stern et al. (2009) are reported in Table S1.

Zircon grains were rinsed in 7N HNO3 at room temperature prior to dissolution. The ROM 205Pb–235U tracer was added to the Krogh-type Teflon dissolution capsules during sample loading. The single zircon crystals were dissolved using ∼0.10 mL of concentrated HF acid and ∼0.02 mL of 7N HNO3 at 200 °C for 4–5 d. Samples were dried to a precipitate and re-dissolved in ∼0.15 mL of 3N HCl overnight (Krogh, 1973). U and Pb were isolated from the bulk zircon solution using ∼50 µL anion exchange columns using HCl, dried in 0.05N phosphoric acid, deposited onto outgassed rhenium filaments with silica gel (Gerstenberger and Haase, 1997), and analyzed with a VG354 mass spectrometer using a single Daly detector in pulse counting mode. Corrections to the 206Pb–238U ages for initial 230Th disequilibrium in the zircon have been made assuming a ratio in the magma of 4.2. All common Pb was assigned to procedural Pb blank. The dead time of the measuring system for Pb and U was 16 and 14 ns, respectively. The mass discrimination correction for the Daly detector is constant at 0.05 % per atomic mass unit. Amplifier gains and Daly characteristics were monitored using the SRM 982 Pb standard. Thermal mass discrimination corrections were 0.10 % per atomic mass unit for both Pb and U. Decay constants are those of Jaffey et al. (1971). All age uncertainties quoted in the text, tables, and error ellipses in the concordia diagrams are given at the 95 % confidence interval. VG Sector software was used for data acquisition. In-house data reduction software in Visual Basic by Donald W. Davis was used. Plotting and age calculations were done using Isoplot 3.76 (Ludwig, 2003).

2.5.2 SIMS U–Pb

The SIMS analyses were performed on the Geoscience Australia SHRIMP IIe. This is a single collector, duoplasmatron-only SHRIMP installed in 2008 at Geoscience Australia by the manufacturer, Australian Scientific Instruments (ASI). The SHRIMP has been upgraded over the years, specifically with a larger diameter post-ESA quadrupole lens for better refocusing of high-energy ions and a piezoelectric stage. This stage, designed and built by ASI, uses three orthogonal SmarAct linear piezo actuators to achieve submicron positional reproducibility in all directions. This reduces working distance changes and secondary (QT1Y) steering variation between spots.

The SHRIMP extracted secondary ions at approximately 675 V before accelerating them to 10 kV and steering them into the 110 µm source slit of the Matsuda (1974) mass spectrometer. The collector slit was set to 100 µm, yielding a mass resolution () of approximately 5000 at the 1 % peak height level. The energy window was left wide open to accept ions with an energy spread of approximately −40 to +60 eV of forward energy relative to the acceleration potential. After mass analysis, ions were detected using an ETP electron multiplier. The retardation lens was not used. Electron multiplier dead time (25 ns) had previously been determined using Ti isotopic ratios in rutile. Analytical spots were programmed daily and run in approximately 23 h batches.

For the reference zircons (mount GA6363, session 170123), after an initial concentration reference zircon (M127; Nasdala et al., 2016) was run, 42 spots were run on each of the eight zircon samples in a round-robin fashion. A 100 µm Köhler aperture was used to produce an elliptical flat-bottomed sputter crater approximately 22 µm × 16 µm across and roughly 0.8 µm deep. The primary beam monitor (PBM) measured a net sample current of 1.9 nA, which corresponds to a true primary beam current of 1.2 nA when analyzing zircon. The acquisition table consisted of six scans through a 10-mass-station run table: 90ZrO (2 s), 204Pb (20 s), background (204Pb + 0.05 amu), (20 s), 206Pb (15 s), 207Pb (40 s), 208Pb (5 s), 238U (5 s), 232Th16O (2 s), 238U16O (2 s), 238U16O2 (2 s).

For the S-type zircon (mount GA6364, session 170124), 36 rims from both the CA and untreated aliquots of Mount Painter Volcanics zircon were run. This was followed by approximately 70 core analyses on each sample, in the manner of a sedimentary detrital zircon study. Untreated TEMORA-2 (Black et al., 2004) zircon was used as the primary reference zircon, with untreated 91500 and untreated OG1 zircon run as the secondary reference zircon and reference zircon, respectively. The run table and other analytical conditions were unchanged from the previous session. A follow-up session (210046) was run using the same settings on the chemically abraded Mount Painter Volcanics rims which initially had anomalously young or old ages.

SHRIMP U–Pb data were processed using Squid 2.5 (Ludwig, 2009). This software dead-time-corrects, background-subtracts, and normalizes the data to the secondary beam monitor (SBM) to remove the effects of changes in the secondary beam intensity before using Dodson (1978) interpolation to calculate isotopic ratios. The 204Pb isotope was used for common Pb correction of both the reference zircon and the unknowns, as 204Pb overcounts were within uncertainty of zero for all sessions, and the 207Pb correction cannot be applied to OG1 due to the common Pb intersection line being parallel to concordia around 3400–3500 Ma.

As the purpose of this study is to see if chemical abrasion, automated analysis, and piezoelectric positioning can improve spot-to-spot error, for this study we start with a default spot-to-spot error of zero and assign spot-to-spot uncertainty expansion only if the probability of fit for the calibration line in the primary reference material is less than 0.05.

2.5.3 SIMS δ18O

The analytical procedures for SHRIMP SI oxygen isotope analysis closely follow those employed by Ávila et al. (2020). A ca. 5 nA Cs+ primary ion beam is focused to a 25 µm × 20 µm spot. Charging is neutralized through focusing of a 2.2 kV electron beam on to the sputter area. Oxygen isotopes were measured in multiple collection mode with 16O and 18O measured across 1011 Ω resistors. Data were reduced with the ANU data reduction program POXI.

2.5.4 SIMS OH and F

While the OH peak with a nominal mass of 17 amu was measured during the δ18O measurements, an additional experiment was run in which the 16O1H−(17), 18O−, and 19F− ions were simultaneously collected and measured. This is because zircon can contain structural OH in the lattice (Trail et al., 2011), and we wished to determine whether the HF dissolution step might also result in F for OH substitution in the structurally sound zircon matrix during chemical abrasion. The analytical procedure is similar to that of Beyer et al. (2016), where OH in the low-mass faraday cup and fluorine in the high-mass cup are both ratioed to 18O in the center cup. Fluorine concentration was normalized using a 91500 concentration of 15 ppm (Coble et al., 2018).

Because the zircon grains were mounted in epoxy, there was a substantial OH background, which decreased over time as the mount degassed in the source chamber of the mass spectrometer. This changing background was subtracted out using the linear slope of the 91500 data from the entire session.

2.5.5 SIMS trace elements

SIMS trace element analyses were done on the SHRIMP IIe single collector instrument at Geoscience Australia following the LASS analyses and epoxy filling of the laser holes. The primary beam was a ∼1.9 nA (net current; as measured by the primary beam monitor – true current approximated at 1.2 nA) beam of O ion focused into an 16 µm × 22 µm spot through the use of a 100 µm Köhler aperture. The method used was similar to Beyer et al. (2020) but with a few changes in mass stations.

Energy filtering was used to exclude low-energy secondary ions. The low-energy shutter was inserted 5.5 mm, sufficient to reduce the 238U peak on metamict zircon by 90 %. In order to optimize the extraction of high-energy ions from the sample and transmission from the sample through the source slit of the mass spectrometer, the extraction voltage was dropped from 675 to 625 V. The total acceleration remained 10 kV, with the difference in voltage accelerating the ions between the extraction plate and the acceleration cone.

The magnet cycled through a run table containing the following masses: 16O+, 19F+, 27Al+, 30Si+, 31P+, 44Ca+, 28Si16O+, 49Ti+, 56Fe+, 89Y+, 90Zr28Si16O+, 139La+, 140Ce+, 143Nd+, 146Nd+, 147Sm+, 149Sm+, 153Eu+, 155Gd+, 157Gd+, 159Tb+, 161Dy+, 163Dy+, 165Ho+, 166Er+, 167Er+, 169Tm+, 171Yb+, 172Yb+, 175Lu+, 179Hf+, 180Hf+, 232Th+, 238U+.

The elements F, Al, P, Ca, and Fe were standardized using the reference zircon 91500. All other elements were standardized using the G7 reference zircon. Reference zircons M127 and G8 (Nasdala et al., 2016, 2018) were used as secondary reference materials. Uncertainties for each spot analyses were calculated by adding in quadrature the uncertainty from the analytical spot to the uncertainty of the weighted mean of the reference zircon and the uncertainty in the reference value for that zircon. As all the zircons studied aside from 91500 are zoned and contain substantial trace element variations, the median value was reported for each sample.

2.5.6 Laser ablation split-stream ICP Hf isotopic and trace elemental analyses

Hf isotopes and U–Pb ages in zircon were simultaneously measured by laser ablation split stream at the Geohistory facility in the John de Laeter Centre, Curtin University, Western Australia. Zircon crystals mounted in 25 mm epoxy rounds were ablated using a Resonetics resolution M-50A incorporating a Compex 102 excimer laser, coupled to a Nu Plasma II multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICPMS) for Hf isotope determination and an Agilent 7700 quadrupole inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Q-ICP-MS) for age and trace element determination. Following two cleaning pulses and a 40 s period of background analysis, samples were spot-ablated for 40 s at a 10 Hz repetition rate using a 50 µm diameter beam and laser energy at the sample surface of 2.2 J cm−2. An additional 15 s of baseline was collected after ablation. The sample cell was flushed with ultrahigh-purity He (320 mL min−1) and N2 (1.2 mL min−1) and high-purity Ar was employed as the plasma carrier gas, split to each mass spectrometer.

For Hf isotope analysis, all isotopes (180Hf, 179Hf, 178Hf, 177Hf, 176Hf, 175Lu, 174Hf, 173Yb, 172Yb, and 171Yb) were counted on the Faraday collector array. Time-resolved data were baseline-subtracted and reduced using Iolite (DRS after Woodhead et al., 2004), where 176Yb and 176Lu were removed from the mass 176 signal using (Chu et al., 2002) and (Chu et al., 2002) with an exponential law mass bias correction assuming (Chu et al., 2002). An effective correction factor was determined for each session by iteratively adjusting the ratio until standard corrected ratios on secondary zircon reference materials with varying Yb content yielded values within the recommended range. No correlation was apparent between the abundance of interfering isotopes (Yb or Lu) and corrected ratios. The interference-corrected was normalized to (Patchett and Tatsumoto, 1980) for mass bias correction. Zircons from the Mud Tank carbonatite locality were analyzed together with the samples in each session to monitor the accuracy of the results. A total of 20 analyses of Mud Tank zircon yielded a value of 0.282507±20 (MSWD = 0.8) identical within uncertainty to the recommended value (0.282505±44; Woodhead and Hergt, 2005). OG1 and Plešovice zircons were run to verify the method with weighted average values (OG1 = 0.280607±0.000027, MSWD = 0.87, n=15; Plešovice 0.282466±0.000023, MSWD = 1.2, n=10) determined within uncertainty of their accepted values (OG1 = 0.280560±20, Kemp et al., 2017; Plešovice 0.282482±0.000013, Sláma et al., 2008). In addition, the corrected ratio was calculated to monitor the accuracy of the mass bias correction and yielded an average value of 1.886868±17 (MSWD = 1.3), which is within the range of values reported by Thirlwall and Anczkiewicz (2004). Calculation of εHf values employed the decay constant of Scherer et al. (2001) and the Chondritic Uniform Reservoir (CHUR) values of Bouvier et al. (2008).

For the Q-ICP-MS analysis, the following elements were monitored for 0.01 s each unless otherwise noted: 28Si, 31P, 44Ca, 49Ti (0.05 s dwell), 89Y, 90Zr, 139La, 140Ce, 141Pr, 146Nd, 147Sm, 153Eu, 157Gd, 163Dy, 166Er, 172Yb, 175Lu, 201Hg, 204Pb, 206Pb, 207Pb, 208Pb (0.1 s dwell time on all Pb isotopes), 232Th (0.025 s dwell time), and 238U (0.025 s dwell time). International glass standard NIST 610 and reference zircon GJ-1 were used as primary reference materials to calculate elemental concentrations and to correct for instrument drift (using 29Si and 90Zr as the internal standard elements, respectively, and assuming 14.26 % Si and 43.14 % Zr in the zircon unknowns). NIST 610 was the primary reference material for P, Ca, Zr, Pb, Th, and U determination, while GJ-1 was the primary reference material for Ti, Y, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Tb, Dy, Er, Yb, and Lu. NIST 614 was treated as a secondary reference material for trace element determination with most elements reproducing within 5 % of the recommended value.

The primary dating reference materials used in this study were 91500 (1063.55±0.4 Ma; Schoene et al., 2006) and OG1 (3465.4±0.6 age for isotopic fractionation monitoring; Stern et al., 2009) with Plešovice (337.13±0.37 Ma; Sláma et al., 2008) and GJ-1 (608.53±0.37; Jackson et al., 2004) analyzed as secondary age reference materials. ages and calculated for zircon age reference materials, treated as unknowns, were found to be within 3 % of the accepted value. The time-resolved mass spectra were reduced using the U_Pb_Geochronology4 data reduction scheme in Iolite 3.5 (Paton et al., 2011, and references therein).

The laser spots were run in a different order to the SHRIMP spots, and grain identities were not preserved. A table matching up laser and SHRIMP grain numbers for mount GA6363 (reference zircons) can be found in Table S2. Additionally, the supplementary sample maps, which show all spot analyses, are in Figs. S1 (reference zircons) and S2 (Mount Painter Volcanics).

3.1 Database search

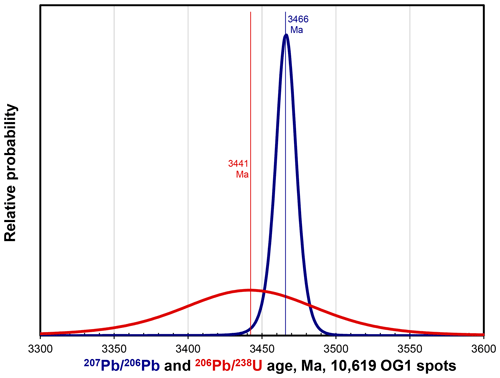

Weighted mean and dates were determined from 10 619 individual SHRIMP spot analyses performed by Geoscience Australia and affiliated organizations since 2007, when the OG1 reference zircon was first introduced. The Tukey's biweight mean date was 3441.08±0.70 Ma (95 %), the median was 3441.64+0.74/−0.81, and the weighted mean was 3365.3±9.2 (95 %), with a large MSWD of 223. For the date, the Tukey's biweight mean date was 3466.11±0.11 Ma (95 %), the median was 3466.16+0.12/−0.13, and the weighted mean was 3465.90±0.19 (95 %), with a MSWD of 4.2.

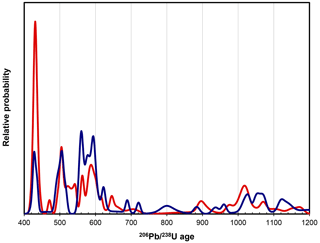

Probability distributions for both dates are shown in Fig. 2.

3.2 ROM calibration and reference zircon age recalculation

Seven aliquots of the gravimetric reference solutions described by Condon et al. (2015) were run at the Royal Ontario Museum. These were three replicates each of the JMM and RP solutions and one of the MIT solution. The results are given in Table S1. The weighted mean ratio of the ROM tracer solution was 106.569±0.1 (2σ), with an MSWD of 0.177 and a very high probability of fit of 0.983. This is well within the previous estimate of 106.54±0.28 (2σ) given in Black et al. (2003). Following the advice of Condon et al. (2015), the central value, and therefore the reference ratio of the reference zircons, was not changed.

McLean et al. (2015) show that the contribution of the tracer uncertainty is smaller than the total analytical uncertainty due to error correlations in the calculations of the tracer solution composition. As we used the same gravimetric solutions as McLean et al. (2015) and the ROM tracer has a similar ratio of ∼100, we scale the tracer uncertainty contribution by 0.53 in a conservative approximation of the scaling of McLean et al. (2015). This gives us a tracer uncertainty contribution of approximately 0.05 % to the systematic uncertainty.

Using this new uncertainty value, we recalculated the reference values for all reference zircons, which are given in Table 1.

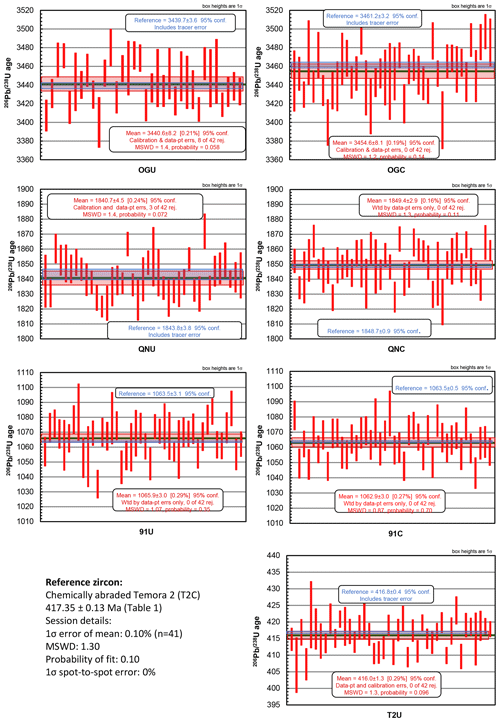

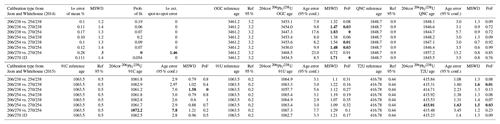

Table 2SHRIMP session 170123 results normalized to (a) T2U values of Table 1 and (b) T2C values of Table 1. For natural OG1 and QGNG samples, where the data do not represent a single population, results are presented both for all data (italics if not a coherent population) and the minimum number of rejections needed to bring the probability of fit above 0.05.

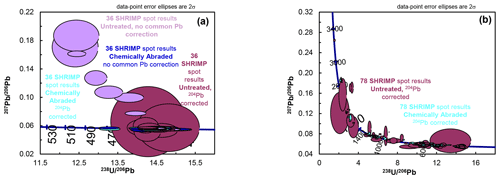

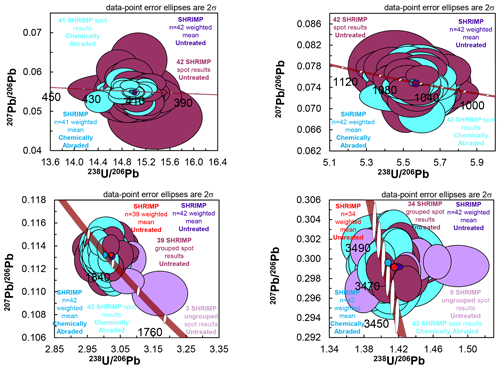

Figure 3Tera–Wasserburg concordia diagrams for all individual SHRIMP spots and means on chemically abraded and untreated reference zircons. (a) TEMORA-2. The concordia band (with uncertainty) is brown with white oval age ticks. (b) 91500. (c) QGNG. (d) OG1. The reference zircon is QNC for panel (a) and T2U for panels (b), (c), and (d).

3.3 SIMS U–Pb results of reference zircons

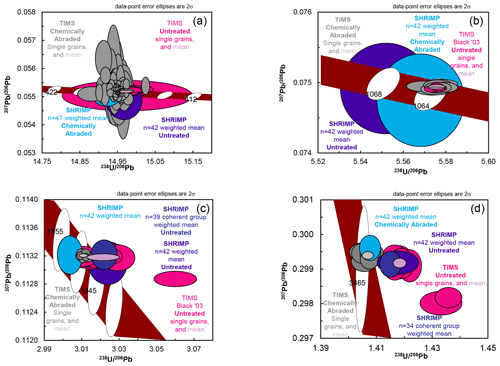

SHRIMP session 170123 generally ran well; only a single analysis (T2C.39.1) had to be discarded due to instrumental instability producing a nonsensical downhole fractionation pattern. 204Pb overcounts were within uncertainty of zero, and the ratios (Tables S3, S4) for both untreated and chemically abraded OG1 were within uncertainty of their respective reference values, indicating no detectable mass-based isotopic fractionation. Individual spot data reduced using the T2U as the primary reference material and reference value from Table 1 are presented in Fig. 3 and Table S3. Individual spot data reduced using T2C as the primary reference zircon and the reference value from Table 1 are presented in Table S4. Measured weighted mean ages of all samples, relative to either T2U or T2C, are shown in Table 2. Weighted means of the spot averages using T2C as the primary reference material and their comparison to the TIMS reference values are shown in Fig. 4. Weighted mean probabilities of fit were better than 0.05 for all chemically abraded samples and for the T2U and 91U zircons, indicating that no excess spot-to-spot error was required in the reduction of this dataset for reference zircons known to reliably exhibit closed-system U–Pb behavior.

In all cases, chemical abrasion reduced the 95 % confidence envelope of the mean, reduced the MSWD, and increased the probability of fit for the weighted mean for unknowns, regardless of which zircon was chosen as the primary reference. The lower MSWD for the chemically abraded samples is not simply a result of larger single spot uncertainty; the central values are also less dispersed. For the chemically abraded samples, the analytical 95 % confidence interval on the means was on the order of ±2 ‰. All chemically abraded ages are within uncertainty of their reference TIMS ages when either T2U or T2C is used as the primary reference material.

The ages for 91U and 91C were within uncertainty of each other, as were T2U and T2C. OGU and QNU, however, were younger and had a dispersed population and a high MSWD compared to OGC and QNC. The population mean, however, had an age consistent with the TIMS ages of untreated, non-chemically abraded zircon (Stern et al., 2009; Black et al., 2003) and not with the chemically abraded ages for those samples (Table 2, Figs. 4, 5).

Figure 5Tera–Wasserburg concordia diagrams of TEMORA-2 (a), 91500 (b), QGNG (c), and OG1 (d) population weighted mean ages. Data are shown with internal errors only to show the difference between the SHRIMP ages from the same analytical session. Data here are standardized to T2U, except for the TEMORA-2 data, which are standardized to QNC. TIMS analyses – both single grain and pooled ages – are shown for comparison as both single grain and weighted mean results. The concordia band (with uncertainty) is brown with white oval age ticks.

Of course, any of these zircons can be used as the reference zircon instead of TEMORA-2. The only pairing of reference zircon and unknown which does not result in the samples being within uncertainty of their reference values is the pair of 91U and OGC (or vice versa), which report an offset on the unknown relative to the reference value of approximately 0.45 % (younger if 91U is the reference and OGC is the unknown, older if the reverse), which exceeds the precision of these measurements. All other reference-unknown combinations result in ages within uncertainty of the reference ages.

Jeon and Whitehouse (2014) showed that for their CAMECA 1280 SIMS instrument, calibration equations which used the UO2 peak instead of the 238U peak were more precise. We checked all of the potential calibration equations presented in Jeon and Whitehouse (2014) to determine if further increases in precision could be achieved. In contrast to their results, we find that calibration equations which use 270(UO2) instead of (or in addition to) 238U offer no improvement relative to the vs. calibration of Claouè-Long et al. (1995). A summary of all eight calibration equations is shown in Table 3. Note that as the calibration variation experiment was performed using a floating calibration slope, there are slight differences between these data and the fixed slope results reported above and in Table 2.

3.4 SIMS U–Pb of Mount Painter Volcanics zircon

SHRIMP session 170124 did not run as smoothly as session 170123. The untreated TEMORA-2 (Black et al., 2004) primary reference material on this mount had an MSWD of 1.71, a probability of fit of 0.0001, and a spot-to-spot error of 0.61 %. The standard error on the 76 TEMORA-2 grain calibration was 0.11 %. The spot-level results for both inherited cores and igneous rims are reported in Table S5.

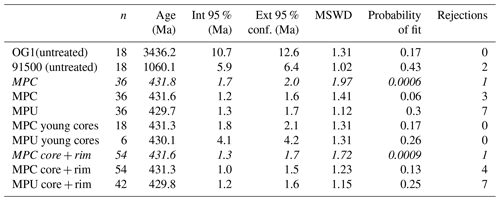

Table 4 ages for samples on the Mount Painter Volcanics mount, standardized to untreated TEMORA-2 zircon (Black et al., 2004). Where the data do not represent a single population, results are presented for both all data (italics if not a coherent population) and the minimum number of rejections needed to bring the probability of fit above 0.05.

TEMORA-2 reference data: n=76; 1 σ standard error of mean = 0.11 %; MSWD = 1.71; probability of fit = 0.0001; spot-to-spot error = 0.61 %.

The weighted mean geochronological results are listed in Table 4. One chip of the untreated secondary reference zircon of 91500 gave two analyses suggesting Pb loss, so these spots were excluded from the mean. The other 16 analyses yielded a age of 1060.1±7.0 Ma. Untreated reference zircon OG1 gave a age of 3436.2±15.5 Ma. Both of these ages are within uncertainty of the reference values in Table 1 for untreated zircon. The OG1 age is younger than the age of this sample and is consistent with the OG1 age of untreated OG1 ages given in Sect. 3.1 of this paper (Table 2a, b, Fig. 4), as well as with several OG1 U–Pb ages reported from this lab over the past decade summarized by Magee et al. (2023).

3.4.1 Igneous age of Mount Painter Volcanics zircon

Seven of the Mount Painter untreated zircon rims have over 1 % common 206Pb, the highest of which is 16 %. Although common Pb corrections pull these analyses back into the same population as the low Pb analyses, we still exclude them from the weighted mean. The remaining 29 untreated Mount Painter rims give a age of 429.7±1.3/1.7 Ma (internal/external). All 29 analyses define a single population, with an MSWD of 1.12 and a probability of fit of 0.30.

The chemically abraded rims are devoid of high common Pb analyses, with common Pb content less than 0.2 % for all spots. Despite this, the results are somewhat more complicated, as the 36 analyses are dispersed, even after including the 0.61 % spot-to-spot error. One of these, spot MPC.21.1, seems to have clipped the edge of a core based on post-analysis CL images and is thus excluded from further consideration. The remaining 35 analyses have a weighted mean age of 431.8±1.7/2.0 Ma with an MSWD of 1.97 and a probability of fit of 0.0006. A probability of fit greater than 0.05 can be achieved by discarding two additional outlier grains, one high and one low, to give an age of 431.6±1.2/1.6 Ma. The non-grouping chemically abraded samples from the Mount Painter Volcanics – both cores and rims – were reanalyzed in session 210046 to see if the difference in age was compositional or analytical (see the Discussion section). Data for session 210046 are in Table S6.

In addition to targeting the rims of these zircon grains for an igneous age, we also dated 78 cores from both the chemically abraded and untreated aliquots of Mount Painter zircon. In both samples the cores yielded a range of ages, but in each case the youngest core population was within uncertainty of the rim age. In the untreated samples, a population of the six youngest cores gave a pooled age of 430.1±4.1/4.2 Ma. The MSWD was 1.31, giving a probability of fit of 0.25. For the chemically abraded samples, there were 18 young cores, which yielded an age of 431.3±1.8/2.1 Ma. The MSWD was 1.31 with a probability of fit of 0.17.

As these populations are indistinguishable from the rim ages, we can combine the youngest cores and the rims to report pooled ages. These give ages of 429.8±1.2/1.6 Ma for the MPU core + rim and 431.3±1.0/1.5 Ma for the MPC core + rim.

3.4.2 Mount Painter Volcanics inherited ages

Most of the cores in both Mount Painter samples were older than the igneous age. None were younger. The Tera–Wasserburg concordia diagrams are given in Fig. 6. There are scattered individual Paleoproterozoic grains in both samples, but they do not form discrete populations in either sample. In both MPC and MPU, the youngest population of cores was within uncertainty of the rim age. However, in the chemically abraded sample, the proportion of these cores was 3 times larger than in the untreated zircon population. Because these cores are indistinguishable in age from the rims for both the untreated and chemically abraded samples, a combined age for both is presented in Table 4, which yields slightly more precise ages than the cores alone due to the larger sample size. It is worth noting, however, that the ∼430 Ma cores have a higher median ratio (0.37) than the ∼430 Ma rims ( = 0.15) and may thus represent an earlier (based on core–rim geometry, not U–Pb age) magma chamber process than the rims.

It is not only the ∼430 Ma cores which change their relative abundance with chemical abrasion. The 550–610 Ma population of MPC is only about half as large as in MPU (Fig. 6).

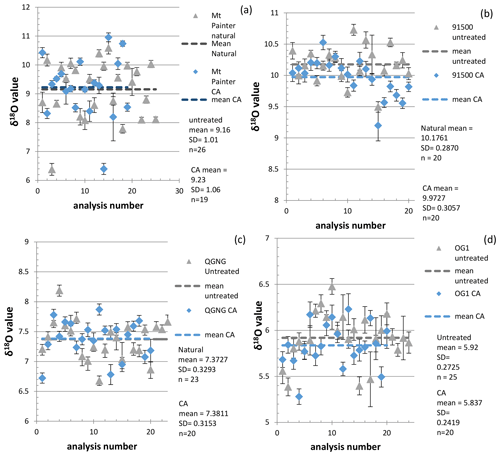

Figure 7δ18O patterns for untreated and chemically abraded zircon populations. Untreated grains are grey triangles; chemically abraded gains are blue diamonds. (a) Mount Painter Volcanics zircon rims. (b) 91500. (c) QGNG. (d) OG1. Uncertainties are 95 % confidence intervals for the weighted mean of all measurements in the population.

3.5 SIMS δ18O results

As the SHRIMP SI can hold up to three round mounts, both GA6363 (reference zircons) and GA6364 (Mount Painter) were loaded and run as a single session. A total of 20–25 spots on each reference zircon were run, as were 20 spots of the rims of MPC and 25 spots on the MPU rims. A total of 35 spots were put on MPU cores, while 30 spots were put on MPC cores. The δ18O results are in Table 5, with complete spot-by-spot data in Table S7. Figure 7 shows plots of δ18O of the samples.

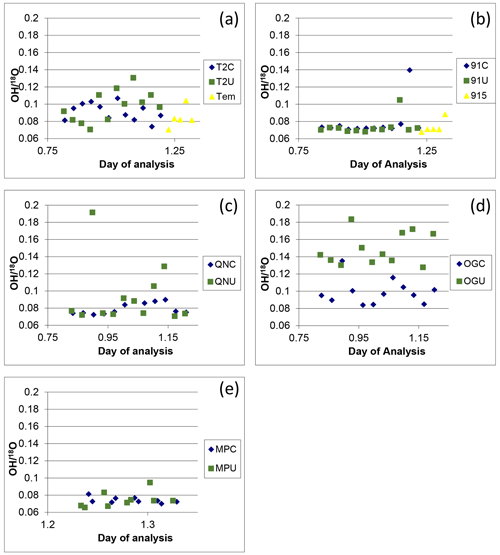

3.6 SIMS trace element results

After the δ18O session reported above, the SHRIMP SI magnet was incremented by 1 amu and the cups were repositioned to measure 16O1H−, 18O−, and 19F− to examine the OH–F systematics in a single analytical volume. The OH–18O–F spot-by-spot results are in Table S8, and the ratios of the samples are plotted in Fig. 8.

Figure 8 plots for various samples. All data have an epoxy degassing trend subtracted out. (a) Untreated (green) and chemically abraded (blue) TEMORA-2. Black is untreated TEMORA-2 on the setup mount. (b) Untreated (green) and chemically abraded (blue) 91500. Black is untreated TEMORA-2 on the setup mount. (c) Untreated (green) and chemically abraded (blue) QGNG. (d) Untreated (green) and chemically abraded (blue) OG1. (e) Untreated (green) and chemically abraded (blue) Mount Painter Volcanics zircon rims.

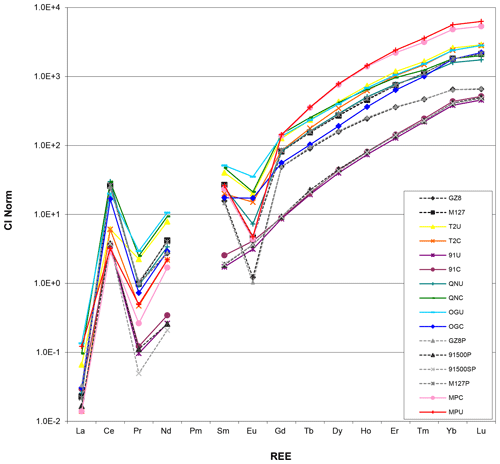

The results for all REE, Hf, Th, U, Y, Ti, P, Al, Ca, Fe, and F measured by SHRIMP IIe as positive ions are given in Table S9. Full spot-by-spot data are in Table S9 for the reference zircons on mount GA6363 and Mount Painter Volcanics zircon on mount GA6364. Titanium-content-based rutile equilibrium temperatures (t(Ti)) are calculated using Ferry and Watson (2007). Phosphorus saturation (Burnham and Berry, 2017) is also shown. REE patterns for the reference zircons are shown in Fig. 9, while the REE patterns for the Mount Painter Volcanics zircon rims are shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9REE plots for the median REE content of the reference and Mount Painter zircons, normalized to chondritic abundances. Secondary (untreated) reference zircons G8 and M127 also shown. The suffix “P” indicates the secondary standard from the Mount Painter analytical session; the suffix “SP” indicates 91500 grains from the setup mount run during the Mount Painter session. Secondary reference zircons have dotted lines, and unknowns have solid lines.

3.7 LASS U–Pb, trace element, and Lu–Hf results

3.7.1 LASS U–Pb results

The laser ICPMS U–Pb geochronology results are presented in Table S10. Total external uncertainties within the system are generally about 0.5 % to 1 % for all untreated samples. Half of samples are within the stated uncertainty of their reference values. The laser results for T2C (410.7±1.5) and 91U (1047.9±8.9) are too young. The laser results for QNU (1859.6±10.2) and OGU (3473.3±16.4) are too old for the untreated reference values but within uncertainty of the chemically abraded reference values. With the exception of 91500, the chemically abraded samples are all younger than the untreated grains. However, this difference was only statistically significant for QGNG. This is the opposite of what was expected from a physical process such as the removal of damaged discordant zircon and is probably the instrumental effect documented by Crowley et al. (2014) and not a physical change in the sample. 91C, which had a grain size much smaller than 91U and suffered more burn-through analyses as a result, appears to have been more affected by common Pb. This may be a surface or epoxy contaminant entrained into the gas flow to the torch when the laser burned through the back or sides of the grain. Spot-by-spot laser U–Pb data are presented in Table S10.

3.7.2 LASS trace element results

Trace elements were analyzed in the same quad ICP mass cycles as the U–Pb isotopes. Due to the dwell time required for Pb isotopes, the LREEs aside from cerium are often below detection limits. Many samples have lanthanum and praseodymium below the detection limit, and in 91500 most of the LREEs are below the detection limit. Spot-by-spot results are listed in Table S11.

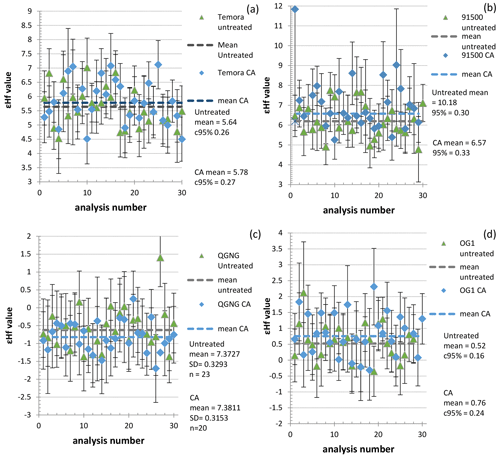

3.7.3 LASS Lu–Hf results

The number of Lu–Hf samples is the same as mentioned above due to the split-stream acquisition. The multicollector-based ratio for each spot is consistent with the trace element data. Table S12 and Fig. 10 show the weighted mean initial Hf isotopic compositions as ratios and as εHf(t). As these geochronology reference zircons have variable Lu–Hf ratios, the mean measured Hf isotopic values are of course more scattered due to variable amounts of ingrowth, particularly for the older zircons (QGNG and OG1). The spot-to-spot data, including the measured and , are in Table S12.

4.1 Database search

A search of 17 years of OG1 data shows that the median age of 3441 Ma agrees well with previous determinations using much smaller datasets (Stern et al., 2009; Magee et al., 2023). The weighted mean is lower than the median or Tukey's biweight due to the influence of a small number of highly discordant spots with dates as low as ∼100 Ma. For this reason we think the median or Tukey's biweight is more robust. These very high Pb-loss domains are also the main cause of the very high MSWD, but even ignoring this severe discordance, there is still substantial excess scatter due to the mixing of spot data from different sessions without any consideration of session uncertainty. Despite this, the median date is very close to both the Magee et al. (2023) average of 16 individual SHRIMP sessions run on the GA SHRIMP between 2008 and 2019 and the Stern et al. (2009) ID-TIMS date for untreated OG1.

These data were collected on four different SIMS instruments (three different SHRIMP II instruments and one SHRIMP RG) at three different institutions (Geoscience Australia, the Australian National University, and Curtin University) by 19 different analysts, so we feel they are representative of a variety of spot placement approaches. Despite this, there is no peak or shoulder at ∼3465 Ma. Asking the Isoplot “unmix ages” function to extract such a peak by seeding it with one at either 5 % or 10 % abundance fails to produce a population of this age. Thus we are confident that the 3440 Ma date presented in this study is representative for untreated OG1 zircon.

4.2 ROM tracer recalibration and reference values

The recalibration of the ROM tracer reduces the systematic uncertainty by a factor of 5 relative to the values published in Black et al. (2003, 2004). This in turn reduces the uncertainty in the reference ages by 140 %–290 %, depending on the reference zircon (noting that only Black et al., 2004, explicitly report an uncertainty including the tracer; Black et al., 2003, and Stern et al., 2009, leave that calculation as an exercise for the reader). As a result, the tracer uncertainty is now much smaller than any of the other uncertainty components from these U–Pb SIMS results, allowing us to compare the results without the complication of an order-of-magnitude tracer uncertainty difference. We recommend the reference values in Table 1 be used for all listed non-chemically abraded reference zircons used to standardize in situ analyses for this reason.

4.3 SIMS U–Pb analyses of reference zircons

SIMS U–Pb analyses of both chemically abraded and untreated zircon show that both CA and untreated material can be used interchangeably and dated against each other, so long as the corresponding reference value is used. Analyses of CA material are more precise, without any systematic discrepancies appearing at the 0.25 %–0.4 % level. This suggests that for well-behaved reference zircons, using a piezo stage, automated analyses, and chemical abrasion, precision substantially better than the 1 %–3 % value quoted by Schaltegger et al. (2015) can be achieved without sacrificing accuracy.

The dependence of accuracy on these particular reference values can be assessed by using alternative reference values. For example, Huyskens et al. (2016) report independent values for T2C, 91C, and OGC. Using their T2C value, the recalculated 91C and OGC values are 1063.8±3.0 for 91C and 3456.8±6.6 for OGC, which overlap the uncertainty envelopes of the Huyskens et al. (2016) reference ages. Reducing the data to the T2C values of Davydov et al. (2010), Ickert et al. (2015), or Von Quadt et al. (2016) instead of the Schaltegger et al. (2021) or Huyskens et al. (2016) values does not significantly alter the results.

The ability to reproduce CA reference values in SIMS analysis of CA material suggests that chemical abrasion ameliorates Pb loss at the scale of the 22 µm × 16 µm × 0.8 µm sputter craters. SIMS ages of chemically abraded OG1 and QGNG zircon are within uncertainty of the CA-ID TIMS ages, but not the untreated TIMS ages. In contrast, the SIMS ages of untreated OG1 and QGNG (whether standardized to T2U or T2C) are within uncertainty of the least discordant population of the TIMS results of untreated zircon, even after discordant grains are excluded to form a coherent population (Fig. 5). This supports the claim made both by Black et al. (2003) for QGNG and by Stern et al. (2009) and Magee et al. (2023) for OG1 that the pooled untreated TIMS age represents the age of SHRIMP spots on untreated material better than the TIMS age (with or without chemical abrasion) or the chemically abraded TIMS age.

Bodorkos et al. (2009) suggested that sufficiently careful SIMS spot placement might avoid areas of Pb loss, while Magee et al. (2016) showed (supplementary figures DR12 and DR 13 of that paper) that in Paleoarchean detrital zircons, 1 µm deep SHRIMP spots show less Pb loss than 10–20 µm deep laser ICPMS craters. However, the data presented here imply that there is a level of subtle discordance that cannot be avoided in SIMS analyses of untreated zircon by spot selection using transmitted, reflected, and cathodoluminescence imaging. In other words, the dissolution of discordant zircon visible in the form of dissolved zones and channels is not the only change to the zircon; the remaining visually intact material also undergoes a subtle change in U–Pb ratio as a result of chemical abrasion.

It is important to note that the untreated U–Pb date has no physical meaning. The actual time of crystallization for OG1 is almost certainly ∼3465 Ma, consistent with the age of chemically abraded OG1 zircon or the age of both untreated and chemically abraded OG1 zircon. Nothing happened to this rock at ∼3440 Ma; at that time it was just a 25-million-year-old pluton which had presumably cooled to the temperature of the country rock by then. Rather, the natural Pb–U ratio represents a level of Pb loss which SIMS analytical techniques cannot avoid without the use of chemical abrasion. It is pervasive in the sense that no matter how carefully a spot position is chosen, this level of Pb loss (if not more) will be present.

Of course, microanalytical studies such as McKanna et al. (2023) and isotope dilution studies such as Mattinson (2011) show that chemical abrasion is not a pervasive process; it happens in discrete domains where a volume of zircon which includes the isotopically disturbed material has been removed. While there may appear to be conflict between these observations of both pervasiveness and discrete domains, they are reconcilable with a proper consideration of scale.

McKanna et al. (2023) imaged dissolution features in CA zircons from many tens of micrometers all the way down to the limit of their imaging resolution. Stepping down a few orders of magnitude farther, Peterman et al. (2016) show Pb mobility occurring at the scale of crystallographic defect structures that are a mere 10 nm in size, while the scale of alpha recoil (and the associated crystallographic damage) is 30–40 nm (Ewing et al., 2003). As these scales are hundreds to thousands of times smaller than the SIMS sputter craters, a network of nanoscale damage would appear pervasive at the tens-of-micrometers scale of our data. The olivine oxidation–decoration technique (Kohlstedt et al., 1976) is a long-standing example of how reactive gas can penetrate and react with nesosilicates at the crystal defect scale, so it is plausible that partial zircon dissolution occurs in a similar fashion at similar scales.

4.4 SIMS U–Pb of Mount Painter zircon

4.4.1 Igneous rims

The MPU rims are much higher in common Pb than most igneous zircons or the MPC rims. The untreated rims have common 206Pb contents reaching as high as 16 % (Fig. 6). The seven grains which have common 206Pb above 0.5 % have been excluded from the weighted mean age, but the Stacy and Kramers (1975) model of common Pb correction works well enough for them to yield a coherent age of 430.3±1.2/1.6 Ma if included. This well-behaved common Pb correction suggests that the common Pb is close to the model age in composition and is not Proterozoic industrial or environmental contaminant Pb. If the Pb is contained in micro- or nano-inclusions, its presence in the rims might be explained by the rims on these volcanic zircon grains having crystallized rapidly and subsumed inclusions during a volcanic eruption. The lack of common Pb in the chemically abraded zircons is consistent with the chemical abrasion process dissolving the domains which host common Pb.

To better understand the anomalously high common Pb contents in these volcanic S-type zircon rims, we compare them to intrusive equivalents from the same origin. Eight ∼430 Ma S-type granitic zircon overgrowths from Bodorkos et al. (2015) were re-examined to look for high common Pb. In three of these samples, no spots in the igneous overgrowth group had any statistically significant common Pb. Three more had a single common Pb-containing outlier with a raw ratio of less than 0.075. The last two samples had two and seven spots with detectable common Pb, but in no case was the total ratio higher than 0.075 (which is about 1.5 % 206Pbc in the Silurian). So these MPU volcanic S-type zircon rims are much higher in common Pb than granitic S-type zircon rims of Bodorkos et al. (2015).

The 18 chemically abraded cores which were the same age (within uncertainty) as the rims did not have excess scatter. The 18 MPC cores all defined a single coherent population with a probability of fit (PoF) of 0.13 and an age (431.3±2.1 Ma) within uncertainty of the MPC rim age (431.8±1.7 Ma). It is only the MPC rims, not the cores, which fail to group into a single population. The much larger population of syn-eruptive cores in the CA-treated grains as opposed to the untreated grains is interpreted as survivor bias, as the core–rim interface presents an area of weakness for the HF to attack during partial dissolution. Zircon dissolution along this boundary was noted in some surviving grains (Figs. 1, S2).

The igneous ages from the MPC rims are about 1.5 to 2 million years older than those from the MPU rims. This % to % difference is consistent with the offset seen in TEMORA-2, QGNG, and OG1. While we have no self-annealing closure ages for QGNG and Mount Painter, Magee et al. (2017) give U–Th–He dates for OG1 and TEMORA-2 that yield irradiation levels of up to 6.5×1017 α g−1 For TEMORA-2 and up to 2×1018α g−1 for OG1 zircons. These are both over the 6×1017 α g−1 damage limit proposed by McKanna et al. (2024) where Pb loss may occur. The eruption age is unlikely to be the final cooling age for the Mount Painter Volcanics, as this unit was buried and deformed during the Lachlan Orogen. However, a closure time similar to TEMORA-2 (from the same orogen) would yield higher damage levels due to the higher uranium content of the Mount Painter zircon rims (Tables 3 and 6b) relative to TEMORA-2.

Unlike the reference zircons TEMORA-2, 91500, QGNG, and OG1, the MPC rims were not less scattered than the MPU rims. The MPC rims had several outliers that resulted in scatter. Whether or not the high common Pb rims were excluded, the MPU rims yielded a single population with a PoF of either 0.11 or 0.3. In contrast, the chemically abraded zircons had a PoF below 0.001, even after excluding a spot which may have hit part of a core. The increase in scatter in the chemically abraded Mount Painter rims is more difficult to explain, and it occurs in both the younger and older directions. Although Pb diffusion can happen in zircon at 950 °C, it is unlikely to proceed over tens of micrometers in the space of 15 h. Even if the partial dissolution process enhances diffusion, the HF partial dissolution step comes after, not before, the high-temperature annealing. Given the number of high common Pb rims in the untreated rims (7 of 36), it is conceivable that the dissolution of included phases in the rims was incomplete, leaving orphaned U (in the case of the young grain) or orphaned Pb (in the case of the two old grains).

Alternatively, the dissolution of inclusions and metamict zones in the rims may have compromised the sputtering surface. In theory, a nanospongiform surface texture from partial dissolution could cause ion emittance issues that might invalidate the vs. calibration equation. It is not clear why this would be apparent only in the Mount Painter zircon and not the reference material grains, but it could be that the increased dissolution proportion of these grains has increased the probability of any particular spot having anomalous Pb+–U+–UO+ ion emission behavior.

To constrain these various possibilities, the individual zircon grains whose rims did not group in the igneous age group were reanalyzed (session 210046) to see if there was a reproducible difference in the ratio or if the scatter was unreproducible. Both cores and rims were analyzed to determine if the cores were higher or lower in total 206Pb than the rims. The results, shown in Fig. 12, show that the outlier grains from the original session 170124 are not consistently anomalous in ratio or age. This implies an analytical effect relating to the sputtering and emission surface, not a compositional one due to Pb migration across zircon subdomains or orphaned U or Pb from incomplete dissolution.

Figure 11Probability density diagram for inherited zircon core ages for zircon from the Mount Painter Volcanics. Red is chemically abraded. Blue is untreated. Grains older than 1200 Ma are not shown, as they are scattered individuals which do not form populations.

4.4.2 Mount Painter Volcanics cores

Compared MPU, MPC has more igneous age cores and a smaller population of Ediacaran–Cambrian aged cores (Fig. 11). These are recognized as part of the Pacific Gondwana Suite (Fergusson et al., 2001). This is consistent with the Pacific Gondwana cores being more susceptible to loss during the chemical abrasion procedure than other zircon cores in the sample. Similarly, the increase in the proportion of igneous age grains in the chemically abraded sample is consistent with single-generation zircon crystals being more resistant to destruction by the chemical abrasion process than those with overgrowths, where the contacts can be damaged by the partial dissolution step of chemical abrasion (Fig. 1). Donaghy et al. (2024) predicted that the relative populations of detrital zircon grains could change during chemical abrasion; our data support this hypothesis.

Geologically, the dominance of Pacific Gondwana Ediacaran–Cambrian zircon cores with a somewhat subordinate population of 1000–1200 Ma cores is typical of early Paleozoic sediments in Queensland (Fergusson et al., 2002, 2007; Purdy et al., 2016), Victoria (Keay et al., 1999), South Australia (Ireland et al., 1998), and the NSW Lachlan fold belt to the south and east of Mount Painter (Fergusson et al., 2001). So their presence in the Mount Painter Volcanics is consistent with this unit being an S-type dacite sourced from the melting of early Paleozoic sediments (Chappell and White, 1974). The relative dearth of ∼450–480 Ma zircon cores in the Mount Painter Volcanics may indicate derivation from Cambrian or early Ordovician sediments. Alternatively, it may reflect sedimentary transport effects which deprived the source sediments of zircon younger than ∼480 Ma.

4.5 SIMS δ18O discussion

For the 91500, OG1, and QGNG zircons, the change in δ18O mean values between the chemically abraded and unabraded populations was negligible. The TEMORA-2 sample suffers from the heterogeneity problem documented in Schmitt et al. (2019) and proved unsuitable for this experiment.

The Mount Painter Volcanics zircon rims showed substantially more scatter in δ18O composition than the reference zircons. This is consistent with previous observations that the granitic correlates of the Mount Painter Volcanics also have variable rim δ18O (Ickert, 2010). Nonetheless, the mean δ18O value is consistent between the untreated and chemically abraded rims, and they are well within uncertainty of each other.

The Mount Painter Volcanics zircon cores have a wide range of δ18O values, as might be expected of sedimentary zircon grains. For the dozen or so grains of each sample where core and rim analyses were performed on the same zircon grain, there is no evidence that the δ18O composition of the core influences the δ18O composition of the rim. Given the relatively low Ti-in-zircon rutile equilibration temperatures of ∼700 °C (MPU = 690±12 °C; MPC = 690±8 °C, 95 % uncertainty), this is not surprising. Similarly, there appears to have been no core–rim diffusive re-equilibration on the tens-of-micrometers spot diameter scale during the annealing phase of chemical abrasion.

It is worth noting that not all the Mount Painter Volcanics zircon cores are detrital. Cores which are the same age (within uncertainty) as the rims are probably related to some sort of pre-eruptive igneous process. While the geochronology results show that the ratios of these cores are often higher than the rims, no other trace elemental analyses were done on the cores. However, 10 of these young cores were analyzed for δ18O. These results were similar to the rims (between 7 ‰ and 10 ‰, with an average of 8.6±1 ‰) and were not within uncertainty of mantle δ18O values.

4.6 Trace element discussion

While the ratio in zircon was measured in both the first (mass 16–17–18) and second (mass 17–18–19) SHRIMP SI sessions, the OH background was high, presumably due to the epoxy mounting material. This background decreased over time, so the data from the (17–18–19) session, which was run on the same mounts without any sample exchange, had lower backgrounds. The same trends were present in both sessions, but the lower signal background ratio in the first (16–17–18) session increased the scatter.

Although we do not have a way of standardizing OH, the measurements in OGU were both more variable and higher than in OGC. In all other samples, there was no significant difference in OH between the chemically abraded and untreated samples. This is consistent with OG1 being the most open-system zircon we looked at and thus having the most metamictization-related hydration, which the partial dissolution step of chemical abrasion removes. Overall, the low in 91500 and S-type Mount Painter Volcanics cores relative to the I-type OG1, QGNG, and TEMORA-2 zircons is consistent with the observation of Mo et al. (2023) that S-type zircons are drier than I-type zircons.

Fluorine contents in both the chemically abraded and untreated samples are unchanged. The lack of fluorine uptake in OGC is consistent with hydrous material being preferentially dissolved and not with the exchange of fluorine with OH bound in structurally sound zircon. Fluorine measured as 19F− by SHRIMP SI relative to 18O− and 19F+ relative to 30Si+ by SHRIMP IIe gave generally similar values, with the median parts per million (ppm) values for all samples in the low teens when standardized to 15 ppm for 91500 (Coble et al., 2018).

For the other trace elements, little change was noticed. U and Th contents in the chemically abraded OG1 were slightly lower. We attribute this to survivor bias, where higher U and Th grains would accrue more radiation damage and be less likely to survive the chemical abrasion treatment. The Ti contents and indicated temperatures are unchanged to slightly lower in the chemically abraded samples, as are the phosphorus concentrations. This shows that the Ti and P loss documented by Schoene et al. (2010) is happening during isotope dilution and not during chemical abrasion.

Most chemically abraded samples have lower concentrations of highly incompatible elements. As the monovalent LREEs are highly incompatible, this results in larger ratios due to the lower Pr and La concentrations. This was observed by Vogt et al. (2023), and we confirm this pattern in OG1, the Mount Painter Volcanics, and TEMORA-2, with the chemically abraded Pr and La values about half an order of magnitude lower than the untreated ones. We observe the opposite trend in QGNG, which we cannot explain.

4.7 Lu–Hf discussion

The Hf isotopic results are similar for both chemically abraded and untreated reference zircons. Of the eight analyzed reference zircons, only the initial Hf composition of 91U was not within uncertainty of the reference values. There was no pattern in the direction of Hf isotopic change between the chemically abraded and untreated samples, but the chemically abraded results generally had a larger uncertainty. QGNG (both) and OGU were the only reference zircons where the probability of fit for all spot measurements was greater than 5 %. While the suitability of various zircons for use as Lu–Hf reference materials is a large and active field of study that is well beyond the scope of this paper, the 91U results suggest that there may be better Lu–Hf reference zircons than 91500.

The most important conclusion from this study is that untreated and chemically abraded reference values and samples are not interchangeable in SIMS U–Pb analyses if they differ significantly. Analysis of chemically abraded zircons returns the chemically abraded TIMS age; that of untreated zircons returns the TIMS age derived from zircons which did not undergo chemical abrasion. All chemically abraded reference zircon results in this study are more precise, but for the younger reference zircons (TEMORA-2 and 91500), this is a modest effect. Using CA-ID-TIMS reference ages for untreated older reference zircons such as OG1 or QGNG will produce a systematic bias on the order of half a percent: the difference between the reference ages for the untreated and chemically abraded grains observed using both SIMS and TIMS geochronology.