the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Short communication: Updated CRN Denudation collections in OCTOPUS v2.3

Alexandru T. Codilean

Henry Munack

OCTOPUS v2.3 includes updates to CRN Denudation, adding 1311 new river basins to the CRN Global and CRN Australia collections. The updates bring the total number of basins with recalculated 10Be denudation rates to 5,611 and those with recalculated 26Al rates to 561. To improve data relevance and usability, redundant data fields have been removed, retaining only those relevant to each collection. Additional updates include the introduction of several new data fields, the latitude of the basin centroid and the effective basin-averaged atmospheric pressure, both of which improve interoperability with online erosion rate calculators. Other new fields record the extent of present-day glaciers and their potential impact on denudation rates, along with estimates of the percentage of quartz-bearing lithologies in each basin, providing a basis for evaluating data quality. The updated data collections can be accessed at https://octopusdata.org (last access: 1 February 2025) and have been assigned the following digital object identifiers (DOIs): https://doi.org/10.71747/uow-r3gk326m.28216865.v1 (Codilean and Munack, 2024a) for CRN Global and https://doi.org/10.71747/uow-r3gk326m.28216919.v1 (Codilean and Munack, 2024b) for CRN Australia.

- Article

(4261 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The OCTOPUS database was released in 2018 and consisted of a global compilation of cosmogenic 10Be and 26Al measurements from modern fluvial sediment along with optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) and thermoluminescence (TL) data from fluvial sediment archives across Australia (Codilean et al., 2018). Hosted at the University of Wollongong, the database was made accessible to the research community through an Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC)-compliant web service, ensuring standardized and seamless data sharing.

In 2022, a new version of the database (OCTOPUS v2) was released (Codilean et al., 2022), introducing significant backend improvements, an upgraded web application with enhanced functionality, and updates to existing data collections, alongside the addition of new datasets. The CRN Denudation collections were updated, and the fluvial luminescence data were expanded to include OSL and TL ages from aeolian and lacustrine sedimentary archives, now forming the SahulSed collection (Codilean et al., 2022). The new version also introduced SahulArch, a compilation of OSL, TL, and radiocarbon ages from archaeological records in Sahul, namely Australia, New Guinea, and the Aru Islands, connected by formerly lower sea levels (Saktura et al., 2023). Additionally, two partner collections – data that are hosted on the OCTOPUS platform but are not maintained by the OCTOPUS project – were integrated: a global dataset of 10Be and 26Al exposure ages on glacial landforms (https://expage.github.io; last access: 1 February 2025) and a collection of late Quaternary non-human vertebrate fossil ages from Sahul (Peters et al., 2019, 2021). Regarding system architecture, OCTOPUS v2 introduced substantial improvements by migrating to Google Cloud Platform (GCP) with a modular design that fully leverages GCP's cloud services. Additionally, it adopted a fully relational PostgreSQL database, which organizes data both hierarchically and thematically, enabling seamless integration of all constituent data collections. Non-cloud-native components like GeoServer and Tomcat were containerized with Docker, ensuring a fully reproducible platform on GCP. The new platform also maintained support for integration with desktop GIS applications through OGC standards, enabling direct access to geospatial data alongside the upgraded web application. Finally, version 2 of the OCTOPUS database introduced comprehensive online documentation, including detailed information about the relational database. Additionally, a GitHub repository was created to host both the documentation and the source code, while supplementary materials not stored in the database were made available through a Zenodo community (see online documentation for details: https://octopus-db.github.io/documentation; last access: 1 February 2025).

Two additional updates in 2024 introduced new data collections: the SahulChar collection, containing sedimentary charcoal and black carbon records from Australia, New Guinea, and New Zealand (Rehn et al., 2024), and the Indo-Pacific Pollen Database (IPPD), containing palaeoecological pollen data along with site and dating information from Australia and the Indo-Pacific region (Herbert et al., 2024) (both in v2.2). Additionally, SahulSed was expanded in v2.3 to include OSL and TL ages from coastal landforms. Versions 2.2 and 2.3 also introduced updates to CRN Denudation, adding 1311 new river basins to the CRN Global and CRN Australia collections. Key improvements to these include the removal of redundant fields, preserving only those relevant to each collection, and the inclusion of new fields that improve interoperability with online erosion rate calculators (Balco et al., 2008; Marrero et al., 2016; Stübner et al., 2023), enabling us to evaluate the quality of recalculated denudation rates.

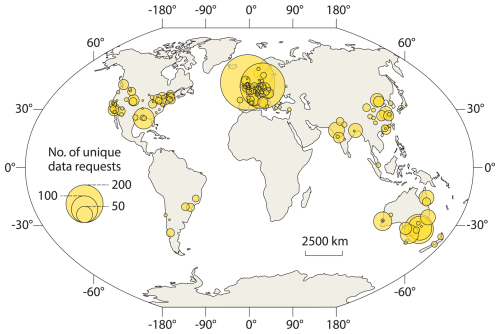

Since its launch in 2018, the OCTOPUS database has recorded nearly 2400 unique data requests (Fig. 1), with approximately 80 % of these requests focused on denudation rate data. The CRN Global and CRN Australia collections have become important resources for the global geoscience community, facilitating synoptic studies at both regional (e.g. Sternai et al., 2019; Delunel et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; Codilean et al., 2021; Whipple et al., 2023) and global scales (e.g. Godard and Tucker, 2021; Zondervan et al., 2023; Halsted et al., 2024; Wilner et al., 2024), as originally intended. Here we describe the updated CRN Global and CRN Australia collections, focusing on spatial data coverage, new data fields, and interoperability with online calculators.

As described in previous publications (Codilean et al., 2018, 2022), CRN Denudation consists of four collections. Two of these, namely CRN Global and CRN Australia, are officially supported by the OCTOPUS project and include recalculated 10Be and, where available, also 26Al denudation rates, and they have been assigned digital object identifiers (DOIs). The remaining two collections – CRN Large Basins and CRN UOW – are included solely for completeness and are available at https://octopusdata.org (last access: 1 February 2025). While they do not contain recalculated rates, CRN Large Basins does include published 10Be and 26Al denudation rate data where available, and both collections are updated with new studies in each release as these become available.

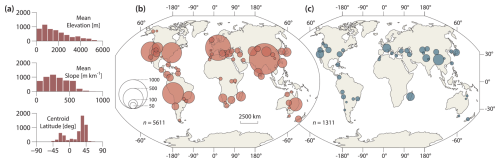

The CRN Global and CRN Australia collections comprise 5611 10Be and 561 26Al recalculated basin-wide denudation rates, based on data published in the peer-reviewed literature up to the start of 2024. As part of the update to version 2.3, 1311 10Be and 163 26Al values were added (see Fig. 2). We note that the extensive 26Al dataset from the recent publication by Halsted et al. (2024) has not yet been incorporated into OCTOPUS. Once included, this addition will significantly increase the number of 26Al data points available in the database. Collectively, the CRN Denudation collections encompass data from 290 studies. A recent literature search suggests that approximately 70 publications contain relevant data not yet captured in OCTOPUS. Therefore, version 2.3 of the OCTOPUS database currently includes about 80 % of all published basin-wide denudation rate studies. Of the 70 missing studies, 47 contain fewer than 10 10Be basin-wide denudation rate estimates per study, with some featuring as few as 2 data points. Only 23 publications contain more than 10 published data points per study, amounting to 363 additional 10Be denudation rates and substantially fewer 26Al rates. Counting all 70 studies, version 2.3 of OCTOPUS captures roughly 90 % of published data points. However, given that the 47 studies with fewer than 10 data points may not be added to the database due to priority being given to larger studies, the current version effectively captures 94 % of the viable data points for inclusion in the database.

Figure 2The updated CRN Global and CRN Australia data collections. (a) The distribution of mean elevation, mean slope, and centroid latitude for the 5611 basins included in version 2.3 of the OCTOPUS database. (b) The geographic distribution of the complete data collections and (c) that of the 1311 newly added basins in version 2.3. Circle size represents the number of requests within each 250 km radius cluster.

In terms of topographic characteristics, the drainage basins of CRN Global and CRN Australia span a wide range of mean elevations and slope gradients (Fig. 2a). The updated dataset has a geographical extent similar to previous versions (Codilean et al., 2018, 2022), with most data still sourced from Northern Hemisphere drainage basins (Fig. 2a). These basins primarily cluster in distinct, tectonically active regions, such as the Pacific coast of the United States, the Appalachians, the European Alps, and the Tibet–Himalaya region (Fig. 2b). Coverage is also strong in the South American Cordillera. The version 2.3 update maintains this general geographical distribution (Fig. 2c), adding new data primarily from basins along the Alpine-Himalayan and circum-Pacific orogenic belts. Importantly, new basins also fill gaps in regions such as the Atlas Mountains in northern Africa, the Caucasus Mountains, and the Tian Shan. However, data from low-gradient, tectonically passive regions remain sparse, particularly in Africa. Nonetheless, the update introduces a substantial dataset from Madagascar and new basins from southeastern Brazil and the Appalachians.

As with previous versions of OCTOPUS, for consistency across the CRN Denudation collections, published 10Be and 26Al concentrations (atoms g−1) were renormalized to the same AMS standards, namely 07KNSTD for 10Be and KNSTD for 26Al (Nishiizumi, 2004; Nishiizumi et al., 2007), and basin-wide denudation rates (mm kyr−1) were recalculated with the open-source program CAIRN (Mudd et al., 2016). The program forward models 10Be or 26Al concentrations at every pixel for a given denudation rate, taking into account latitude and altitude scaling of cosmogenic nuclide production rates along with snow, self-, and topographic shielding. The obtained concentrations are averaged to predict a basin-averaged 10Be or 26Al concentration, and Newton's method is then used to find the denudation rate for which the predicted concentration matches the measured concentration and to derive associated uncertainties. In addition to the vector and attribute data that are stored in the PostgreSQL + PostGIS database, the CRN Global and CRN Australia collections also include seven raster data layers and a series of text files representing CAIRN configuration and input/output files (see Codilean et al., 2022, for details). These additional files are organized in “studies” – each study represents one publication – and are saved as separate zip archives with names keyed to the unique STUDYID identifier assigned to each study. The provision of these data means that users can recalculate denudation rates using updated versions of the CAIRN code, keeping the CRN collections reproducible and reusable into the future.

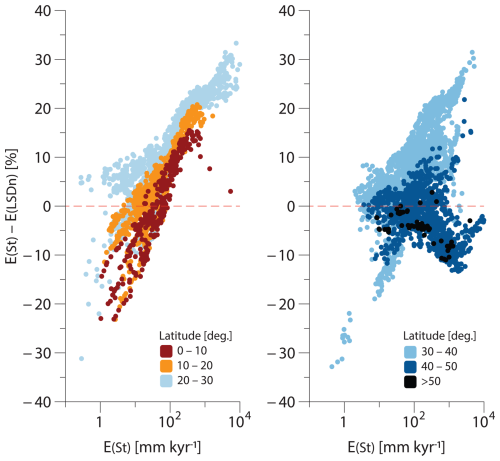

Cosmogenic nuclide-based exposure ages and denudation rates require periodic recalculation, as measurement standards and calculation protocols are regularly updated (Phillips et al., 2016; Schaefer et al., 2022). Online exposure age and erosion rate calculators (e.g. Balco et al., 2008; Marrero et al., 2016) play a crucial role in this process, offering platforms for dynamic and transparent data reduction. These tools harmonize disparate datasets and significantly enhance the reproducibility of cosmogenic nuclide exposure ages and erosion rates (Balco, 2020). Although the CAIRN program operates independently of existing online calculators, it has been our preferred choice for several reasons. Firstly, CAIRN is open-source and packaged in freely available software that runs on all commonly used operating systems. Secondly, it is automated and designed to support reproducibility; users can publish a digital elevation model of their study area along with cosmogenic 10Be and 26Al data and CAIRN input files, ensuring denudation rates can be replicated. Thirdly, CAIRN is part of LSDTopoTools, a suite developed for reproducible topographic analysis (Mudd et al., 2023), allowing basin-wide denudation rate calculations to seamlessly integrate with other topographic analyses within unified workflows. For computational efficiency, however, CAIRN only implements the time-independent Stone–Lal nuclide production scaling scheme (Stone, 2000). This represents a significant limitation, as time-independent and time-dependent cosmogenic nuclide production scaling schemes yield results that vary systematically with denudation rate and latitude (Stübner et al., 2023). Specifically, calculated denudation rates are underestimated in slowly eroding settings and overestimated in rapidly eroding settings when a time-independent scaling scheme, which ignores geomagnetic field strength variations, is used, with differences being the largest at low latitudes (Fig. 3). Therefore, for applications where the use of more up-to-date scaling schemes is desired, users must turn to other packages (e.g. Charreau et al., 2019; Stübner et al., 2023) or make use of CAIRN's spatially averaged products for ingestion in available online calculators.

Figure 3Comparison of 10Be denudation rates calculated using the time-independent Stone–Lal (St) (Stone, 2000) scaling scheme with those calculated using the time-dependent LSDn scaling scheme (Lifton et al., 2014). Note how differences between the St and LSDn scaling schemes vary systematically with denudation rate, being the largest at latitudes of 40° or less. Data points are colour-coded by latitude, with values for <30 and >30° plotted separately for clarity. Modified from Stübner et al. (2023).

To facilitate interoperability with available online erosion rate calculators (e.g. Balco et al., 2008; Marrero et al., 2016), the CRN Global and CRN Australia collections include two additional fields: CENTR_LAT, representing the latitude of the basin centroid, and ATM_PRESS, representing the effective basin-averaged atmospheric pressure. Both parameters are calculated by CAIRN. While the centroid latitude is straightforward, the atmospheric pressure is determined through an iterative process that identifies the pressure value best matching the spatially averaged Stone–Lal production rate (see also Mudd et al., 2016). Therefore, ATM_PRESS should provide a fairly accurate single-value approximation of the spatially distributed altitude scaling factor for any given basin. It is important to note, however, that, unlike the spatially distributed atmospheric pressure derived by CAIRN, which maps elevation values to atmospheric pressure using the NCEP2 climate reanalysis data (Compo et al., 2011), ATM_PRESS is not obtained from an atmospheric model. Instead, it is calculated by inverting the spatially distributed scaling model and, as such, holds no meteorological significance.

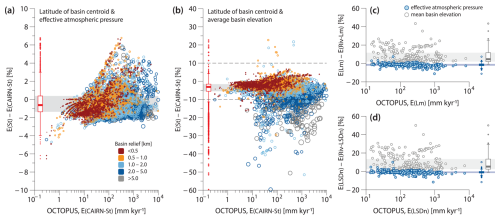

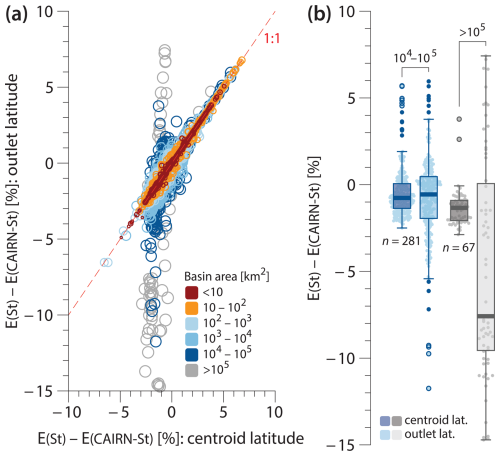

Using CENTR_LAT and ATM_PRESS with the Stone–Lal (St) scaling scheme in the Balco et al. (2008) online calculator yields 10Be denudation rates that very closely match those calculated with CAIRN (Fig. 4a). For example, the median difference between values calculated with the Balco et al. (2008) calculator and those calculated with CAIRN, when using the St scaling scheme, is only −0.6 % (mean = −0.3 %), with an interquartile range (IQR) between −1.4 % and 0.4 % and a total range between −6.5 % and 6.8 %. These values are below the analytical uncertainties of the measured 10Be concentrations recorded in the database, namely 4.8 % (median), 7.4 % (mean), and 3.0 %–8.6 % (IQR), and well below the uncertainties of the calculated denudation rates. Recalculating denudation rates with the online calculator using the mean basin elevation instead of ATM_PRESS yields larger differences (Fig. 4b): −3.1 % (median), −4.4 % (mean), and −5.5 % to −1.6 % (IQR). Although these values are still within uncertainties of both 10Be concentrations and recalculated denudation rates, differences shown in Fig. 4b correlate with basin relief, with the total range of differences being −143 % to 23 %. Therefore, using the effective atmospheric pressure (ATM_PRESS) instead of the mean elevation is recommended, as it reliably accounts for basin relief variations.

Figure 4Comparison of 10Be denudation rates in the OCTOPUS database with those calculated using version 3 of the Balco et al. (2008) online erosion rate calculators. (a) Percent difference between 10Be denudation rates calculated using the St scaling scheme in the Balco et al. (2008) online calculators and those calculated with CAIRN (Mudd et al., 2016). Calculations are based on the basin centroid latitude and effective atmospheric pressure. (b) Same as panel (a) but swapping effective atmospheric pressure with the mean basin elevation. (c) Percent difference between 10Be denudation rates calculated using the Lm scaling scheme in the Balco et al. (2008) online calculators and those calculated with RIVERSAND (Stübner et al., 2023) using the same Lm scaling scheme. (d) Same as panel (c) but using the LSDn scaling scheme. In panels (a) and (b), the size and colour of symbols indicate the total basin relief (km). In panels (c) and (d), blue symbols denote values calculated using the effective atmospheric pressure, whereas grey symbols indicate values derived using the mean basin elevation. Shaded grey areas depict interquartile ranges (IQRs), and the dashed horizontal lines in panel (b) denote the y-axis range from panel (a).

Basin relief covaries with basin area to some extent, with the largest basins in OCTOPUS also generally exhibiting the highest relief. To test how much of the scatter in Fig. 4b is due to basin relief versus basin area, we recalculated all denudation rates with the Balco et al. (2008) calculator using ATM_PRESS and swapping CENTR_LAT with the latitude of the basin outlet (Fig. 5). Results are virtually identical for basins smaller than 104 km2 and only become significant for basins larger than 105 km2 (Fig. 5b). Given that there are only 67 basins (∼1 % of the total) in CRN Global and CRN Australia that are larger than 105 km2, the choice of latitude will not matter for most applications. Nevertheless, we recommend using CENTR_LAT over the latitude of the basin outlet, as the former is a better single-value approximation of the spatially distributed latitude scaling for any given basin.

Because CAIRN only implements the time-independent St scaling scheme, it cannot be used to test how well CENTR_LAT and ATM_PRESS perform with time-dependent scaling schemes, specifically Lm (Nishiizumi et al., 1989) and LSDn (Lifton et al., 2014), as implemented in the Balco et al. (2008) calculator. To rigorously calculate 10Be denudation rates using Lm and LSDn, we used RIVERSAND – a recently developed frontend to the Balco et al. (2008) calculators that determines basin-wide denudation rates, taking into account river basin hypsometry (Stübner et al., 2023) – and compared the resulting output to that obtained by using CENTR_LAT and ATM_PRESS with the Balco et al. (2008) calculator. For our comparison, we selected eight studies from CRN Global, comprising 290 10Be data points. These studies included high-relief basins with a median relief of 3.6 km and a range spanning from 0.6 to 8.7 km. Differences between the two approaches are within a few percent (Fig. 4c and d) for both Lm (median = −1.3 %, mean = −1.8 %, IQR = −2.5 % to −0.5 %) and LSDn (median = −1.0 %, mean = −1.2 %, IQR = −1.8 % to −0.1 %). These results indicate that CENTR_LAT and ATM_PRESS are suitable approximations of basin characteristics, even in high-relief settings, and should therefore reliably reproduce denudation rates calculated using the Lm and LSDn time-dependent scaling schemes as implemented within a more rigorous, spatially distributed approach.

Figure 5Comparison of 10Be denudation rates calculated using basin outlet latitude versus centroid latitude. (a) Percent difference between the St scaling scheme in Balco et al. (2008) and CAIRN, comparing results using outlet latitude versus centroid latitude. Symbol size and colour represent the total basin area (km2). (b) Box plots showing the same as in panel (a) for basins with areas of 104−105 km2 (blue) and >105 km2 (grey).

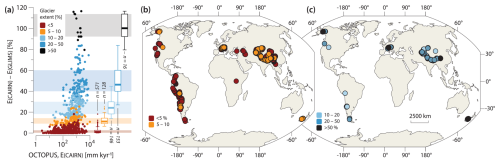

According to the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) database (Raup et al., 2007), 1014 CRN Global basins are presently glaciated. While, in just over 50 % of these basins (n=571), present-day glacier coverage is below 5 % of the total basin area, the database includes 169 basins with present-day glacier coverage over 20 % and 16 basins where more than half of the basin area is covered by ice (Fig. 6). Not accounting for glacier-ice shielding will result in an overestimation of 10Be-derived denudation rates (Schaefer et al., 2022). To estimate the potential extent of this overestimation, we calculated end-member 10Be-derived denudation rates for the 1014 affected CRN Global basins using present-day glacier extents from the GLIMS database. This calculation assumes that glaciated areas contribute sediment in proportion to their surface areas, with this sediment having a 10Be concentration of zero. While glaciated areas may indeed contribute sediment that is depleted in cosmogenic nuclides, due to both shielding from cosmic rays and potential excavation from depth, it is improbable that glaciated areas contribute sediment strictly in proportion to their surface areas. Therefore, our glacier-corrected 10Be denudation rates represent end-member minimum values, and the differences from the uncorrected 10Be denudation rates in the OCTOPUS database reflect end-member maximum values.

Figure 6The influence of present-day glacier coverage on calculated 10Be denudation rates. (a) Percent difference between 10Be denudation rates calculated without glacier correction and those adjusted for the maximum impact of present-day glacier cover on diluting the 10Be signal exported by rivers from each affected drainage basin (see text for details). Colours indicate present-day glacier extent (%), with box plots summarizing percentage difference statistics for each colour band. Glacier extent data are sourced from the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) database (Raup et al., 2007). (b–c) Geographic distribution of CRN Global basins with present-day glacier coverage, presented on two maps for visual clarity.

To our knowledge, corrections for glacier coverage in denudation rate calculations are rarely attempted in the literature, primarily because doing so accurately is impossible due to lack of relevant data. Nevertheless, the median difference between corrected and uncorrected 10Be-derived denudation rates for basins with present-day ice occupying between 10 %–20 % of basin area (n=146) may be as high as 24 %, and, for basins with 20 %–50 % glacier coverage (n=153), this value may be as high as 46 %, for example (Fig. 6), exceeding the uncertainties of the calculated denudation rates. While our calculations represent end-member values, they may still provide valuable insights into the potential influence of glaciers on the overestimation of 10Be-derived denudation rates when no correction is applied. To this end, the updated CRN Global collection includes five additional data fields: EBEGLA and EBEGLA_ERR, which represent the glacier-corrected 10Be denudation rates and associated uncertainties as calculated by CAIRN; EBE_DIFF, indicating the percentage difference between 10Be denudation rates calculated without glacier correction and those adjusted for maximum present-day glacier impact; and GLA_KM2 and GLA_PCNT, representing the areal extent of present-day glaciers in square kilometres (km2) and percentage, respectively. All data and calculations are based on present-day glacier extents from the GLIMS database.

The primary goal of the OCTOPUS project was to create a comprehensive database of cosmogenic nuclide-based denudation rates that is (1) globally consistent, achieved by recalculating all rates using a standardized methodology, and (2) reproducible and reusable, made possible by providing all input geospatial data and extensive metadata and by using open-source tools, such as CAIRN. Adopting a global approach necessitates certain compromises. For instance, it requires selecting a DEM that is global or near global in extent and has a resolution suited to the range of basin areas included. Additionally, some corrections applied in individual studies – such as adjustments for quartz abundance variations or snow shielding – may be impractical for a global database due to a lack of consistent global data for these specific corrections.

While the absence of detailed meteorological data on snow thickness prevents us from evaluating the potential bias introduced by omitting snow shielding corrections in our recalculated denudation rates, globally consistent, albeit low-resolution, lithological data are available. Although these data are insufficient for precise corrections related to quartz abundance, they may still be useful for assessing the overall quality of the recalculated data. To this end, CRN Global and CRN Australia include an additional field, labelled QTZ_PCNT, which indicates the percentage of basin area underlain by quartz-bearing rocks. These data were sourced from the Global Lithological Map (GLiM) by Hartmann and Moosdorf (2012). To identify the spatial distribution of quartz-bearing rocks, we filtered the GLiM dataset by excluding specific lithological groups. Carbonate-rich sedimentary rocks and evaporites were removed, specifically those classified as carbonate sedimentary (sc), evaporite (ev), and also mixed sedimentary (sm) when the presence of carbonates was indicated. Additionally, we excluded groups classified as basic volcanic (vb) and basic plutonic (pb). Finally, metamorphic rocks (mt), with a secondary classification of mafic metamorphic (am), were also excluded. To reiterate, for most basins, these data are too coarse to enable precise corrections to the recalculated denudation rates; however, they may still offer valuable insights and help identify basins where such corrections could be warranted. For example, in only ∼65 % (n=3681) of the basins in CRN Global and CRN Australia, quartz-bearing rocks constitute more than 90 % of the basin area. Quartz-bearing rocks constitute less than half of the basin area in ∼15 % (n=869) of basins and less than 10 % of basin area in ∼6 % (n=351) of basins.

To maintain consistency with previous database versions, the 10Be and 26Al denudation rates in the CRN Global and CRN Australia collections were corrected for topographic shielding using the method outlined in Codilean (2006). However, a recent study by DiBiase (2018) suggests that topographic shielding corrections are generally unnecessary for calculating basin-wide denudation rates, except in steep catchments where quartz distribution and/or denudation rates are not uniform. Nevertheless, the effect of topographic shielding corrections is minimal. In the case of 10Be, for example, the median difference between denudation rates calculated with and without correcting for topographic shielding is only ∼1 % (IQR = 0.3 to 2.6 %), and ∼99 % of the data have differences below the median uncertainty of the calculated denudation rates. Thus, while disregarding topographic shielding yields slightly higher denudation rates, these differences fall within the current uncertainty levels. Given the computational cost, a recalculation of the CRN Global and CRN Australia collections without topographic shielding correction using CAIRN is not justified. To address the issue of topographic shielding, however, and enable users to directly compare denudation rates with and without this correction, we include in CRN Global and CRN Australia the 10Be and 26Al denudation rates calculated using CENTR_LAT and ATM_PRESS with the LSDn scaling scheme in the Balco et al. (2008) calculator, both with and without correcting for topographic shielding.

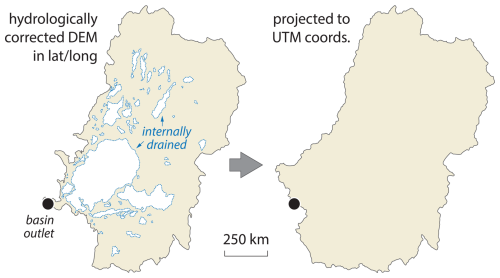

The CAIRN program requires input DEM data to be projected into one of the WGS84 UTM zones. This DEM is then used to derive a flow network, delineate individual basins, and link each grid cell within the basin to the sampling sites at the outlet. The requirement to project data into WGS84 UTM zones can pose challenges for large river basins that span multiple UTM zones. In such cases, the DEM must be projected into one of these zones, which increases distortion in the resulting DEM. Moreover, the requirement to project data introduces challenges in low-relief regions, such as the interior of the Australian continent (Tooth, 1999), where internally drained areas within drainage basins are common. Projecting the data in such areas can artificially connect these internally drained sub-basins to the main drainage network (Fig. 7). Fortunately, due to the subdued topography in these regions, any errors in the calculated basin-wide production rates are minimal. Nevertheless, basins with significant errors have been excluded from the database.

Figure 7Drainage basin of the Murray and Darling rivers as derived from a hydrologically corrected DEM (left) versus that derived by CAIRN from the same DEM after projection to UTM coordinates (right). Note the absence of internally drained areas and the shifts in the location of the drainage divide following projection. See text for more details.

OCTOPUS v2.3 introduces updates to CRN Denudation, expanding the CRN Global and CRN Australia collections with 1311 additional river basins. These updates bring the total number of basins with recalculated 10Be denudation rates to 5611 and those with recalculated 26Al rates to 561. Enhancements to data relevance and usability were achieved by removing redundant fields, ensuring that only essential information remains for each collection. New data fields now include the latitude of each basin's centroid and its effective basin-averaged atmospheric pressure, improving interoperability with online erosion rate calculators. Additional fields track the extent of present-day glaciers and their potential influence on denudation rates, along with estimates of quartz-bearing lithologies in each basin, providing a framework for evaluating data quality. We hope that the OCTOPUS database will continue to ensure data reusability well beyond the scope of their initial collection, thereby enabling large-scale, synoptic studies that would otherwise be unattainable.

OCTOPUS v2.3 can be accessed at https://octopusdata.org (last access: 1 February 2025). The updated data collections have been assigned the following DOIs: https://doi.org/10.71747/uow-r3gk326m.28216865.v1 for CRN Global (Codilean and Munack, 2024a) and https://doi.org/10.71747/uow-r3gk326m.28216919.v1 for CRN Australia (Codilean and Munack, 2024b). Users should refer to the DOIs provided to ensure that they are accessing the current and supported version of the data. Comprehensive online documentation can be accessed at https://octopus-db.github.io/documentation/ (last access: 1 February 2025). Supplementary data that were used in this paper but are not available via the OCTOPUS database can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14014985 (Codilean and Munack, 2024c).

ATC and HM contributed equally to the work presented here.

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank Richard Ott, Greg Balco, and Roman DiBiase for careful reviews of the discussion paper. We also thank the cosmogenic nuclide community for generously sharing their data.

This research has been supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (ARC grant no. CE170100015).

This paper was edited by Marissa Tremblay and reviewed by Richard Ott, Greg Balco, and Roman DiBiase.

Balco, G.: Technical note: A prototype transparent-middle-layer data management and analysis infrastructure for cosmogenic-nuclide exposure dating, Geochronology, 2, 169–175, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-2-169-2020, 2020. a

Balco, G., Stone, J. O., Lifton, N. A., and Dunai, T. J.: A complete and easily accessible means of calculating surface exposure ages or erosion rates from 10Be and 26Al measurements, Quat. Geochronol., 3, 174–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2007.12.001, 2008. a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n

Charreau, J., Blard, P., Zumaque, J., Martin, L. C., Delobel, T., and Szafran, L.: Basinga: A cell-by-cell GIS toolbox for computing basin average scaling factors, cosmogenic production rates and denudation rates, Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 44, 2349–2365, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4649, 2019. a

Chen, Y., Wu, B., Xiong, Z., Zan, J., Zhang, B., Zhang, R., Xue, Y., Li, M., and Li, B.: Evolution of eastern Tibetan river systems is driven by the indentation of India, Commun. Earth Environ., 2, 256, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00330-4, 2021. a

Codilean, A. and Munack, H.: OCTOPUS Database v.2.3: The CRN Denudation Global collection [2024], University of Wollongong [data set], https://doi.org/10.71747/uow-r3gk326m.28216865.v1, 2024a. a, b

Codilean, A. and Munack, H.: OCTOPUS Database v.2.3: The CRN Denudation Australian collection [2024], University of Wollongong [data set], https://doi.org/10.71747/uow-r3gk326m.28216919.v1, 2024b. a, b

Codilean, A. and Munack, H.: Supplementary material for: Updated CRN Denudation collections in OCTOPUS v2.3 (Version 1), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14014985, 2024c. a

Codilean, A., Fülöp, R.-H., Munack, H., Wilcken, K., Cohen, T., Rood, D., Fink, D., Bartley, R., Croke, J., and Fifield, L.: Controls on denudation along the East Australian continental margin, Earth-Sci. Rev., 214, 103543, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103543, 2021. a

Codilean, A. T.: Calculation of the cosmogenic nuclide production topographic shielding scaling factor for large areas using DEMs, Earth Surf. Process. Landf., 31, 785–794, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.1336, 2006. a

Codilean, A. T., Munack, H., Cohen, T. J., Saktura, W. M., Gray, A., and Mudd, S. M.: OCTOPUS: an open cosmogenic isotope and luminescence database, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 10, 2123–2139, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-2123-2018, 2018. a, b, c

Codilean, A. T., Munack, H., Saktura, W. M., Cohen, T. J., Jacobs, Z., Ulm, S., Hesse, P. P., Heyman, J., Peters, K. J., Williams, A. N., Saktura, R. B. K., Rui, X., Chishiro-Dennelly, K., and Panta, A.: OCTOPUS database (v.2), Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 14, 3695–3713, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-3695-2022, 2022. a, b, c, d, e

Compo, G. P., Whitaker, J. S., Sardeshmukh, P. D., Matsui, N., Allan, R. J., Yin, X., Gleason, B. E., Vose, R. S., Rutledge, G., Bessemoulin, P., Brönnimann, S., Brunet, M., Crouthamel, R. I., Grant, A. N., Groisman, P. Y., Jones, P. D., Kruk, M. C., Kruger, A. C., Marshall, G. J., Maugeri, M., Mok, H. Y., Nordli, O., Ross, T. F., Trigo, R. M., Wang, X. L., Woodruff, S. D., and Worley, S. J.: The Twentieth Century Reanalysis Project, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 1–28, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.776, 2011. a

Delunel, R., Schlunegger, F., Valla, P. G., Dixon, J., Glotzbach, C., Hippe, K., Kober, F., Molliex, S., Norton, K. P., Salcher, B., Wittmann, H., Akçar, N., and Christl, M.: Late-Pleistocene catchment-wide denudation patterns across the European Alps, Earth-Sci. Rev., 211, 103407, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103407, 2020. a

DiBiase, R. A.: Short communication: Increasing vertical attenuation length of cosmogenic nuclide production on steep slopes negates topographic shielding corrections for catchment erosion rates, Earth Surf. Dynam., 6, 923–931, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-6-923-2018, 2018. a

Godard, V. and Tucker, G. E.: Influence of Climate‐Forcing Frequency on Hillslope Response, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL094305, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl094305, 2021. a

Halsted, C., Bierman, P., Codilean, A., Corbett, L., and Caffee, M.: Global analysis of in situ cosmogenic 26Al/10Be ratios in fluvial sediments indicates widespread sediment storage and burial during transport, Geochronology Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-2024-22, in review, 2024. a, b

Hartmann, J. and Moosdorf, N.: The new global lithological map database GLiM: A representation of rock properties at the Earth surface, Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 13, Q12004, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012gc004370, 2012. a

Herbert, A. V., Haberle, S. G., Flantua, S. G. A., Mottl, O., Blois, J. L., Williams, J. W., George, A., and Hope, G. S.: The Indo–Pacific Pollen Database – a Neotoma constituent database, Clim. Past, 20, 2473–2485, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-20-2473-2024, 2024. a

Lifton, N., Sato, T., and Dunai, T. J.: Scaling in situ cosmogenic nuclide production rates using analytical approximations to atmospheric cosmic-ray fluxes, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 386, 149–160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.10.052, 2014. a, b

Marrero, S. M., Phillips, F. M., Borchers, B., Lifton, N., Aumer, R., and Balco, G.: Cosmogenic nuclide systematics and the CRONUScalc program, Quat. Geochronol., 31, 160–187, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.09.005, 2016. a, b, c

Mudd, S. M., Harel, M.-A., Hurst, M. D., Grieve, S. W. D., and Marrero, S. M.: The CAIRN method: automated, reproducible calculation of catchment-averaged denudation rates from cosmogenic nuclide concentrations, Earth Surf. Dynam., 4, 655–674, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-4-655-2016, 2016. a, b, c

Mudd, S. M., Clubb, F. J., Grieve, S. W. D., Milodowski, D. T., Gailleton, B., Hurst, M. D., Valters, D. V., Wickert, A. D., and Hutton, E. W. H.: LSDtopotools/LSDTopoTools2: LSDTopoTools2 v0.9, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8076231, 2023. a

Nishiizumi, K.: Preparation of 26Al AMS standards, Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms, 223, 388–392, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2004.04.075, 2004. a

Nishiizumi, K., Winterer, E. L., Kohl, C. P., Klein, J., Middleton, R., Lal, D., and Arnold, J. R.: Cosmic ray production rates of 10Be and 26Al in quartz from glacially polished rocks, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 94, 17907–17915, https://doi.org/10.1029/jb094ib12p17907, 1989. a

Nishiizumi, K., Imamura, M., Caffee, M. W., Southon, J. R., Finkel, R. C., and McAninch, J.: Absolute calibration of 10Be AMS standards, Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms, 258, 403–413, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2007.01.297, 2007. a

Peters, K. J., Saltré, F., Friedrich, T., Jacobs, Z., Wood, R., McDowell, M., Ulm, S., and Bradshaw, C. J. A.: FosSahul 2.0, an updated database for the Late Quaternary fossil records of Sahul, Sci. Data, 6, 272, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0267-3, 2019. a

Peters, K. J., Saltré, F., Friedrich, T., Jacobs, Z., Wood, R., McDowell, M., Ulm, S., and Bradshaw, C. J. A.: Addendum: FosSahul 2.0, an updated database for the Late Quaternary fossil records of Sahul, Sci. Data, 8, 133, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00918-7, 2021. a

Phillips, F. M., Argento, D. C., Balco, G., Caffee, M. W., Clem, J., Dunai, T. J., Finkel, R., Goehring, B., Gosse, J. C., Hudson, A. M., Jull, A. T., Kelly, M. A., Kurz, M., Lal, D., Lifton, N., Marrero, S. M., Nishiizumi, K., Reedy, R. C., Schaefer, J., Stone, J. O., Swanson, T., and Zreda, M. G.: The CRONUS-Earth Project: A synthesis, Quat. Geochronol., 31, 119–154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2015.09.006, 2016. a

Raup, B., Racoviteanu, A., Khalsa, S. J. S., Helm, C., Armstrong, R., and Arnaud, Y.: The GLIMS geospatial glacier database: A new tool for studying glacier change, Global Planet. Change, 56, 101–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2006.07.018, 2007. a, b

Rehn, E., Cadd, H., Mooney, S., Cohen, T. J., Munack, H., Codilean, A. T., Adeleye, M., Beck, K. K., Constantine IV, M., Gouramanis, C., Hanson, J. M., Jones, P. J., Kershaw, A. P., Mackenzie, L., Maisie, M., Mariani, M., Mately, K., McWethy, D., Mills, K., Moss, P., Patton, N. R., Rowe, C., Stevenson, J., Tibby, J., and Wilmshurst, J.: The SahulCHAR Collection: A Palaeofire Database for Australia, New Guinea, and New Zealand, Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2024-328, in review, 2024. a

Saktura, W. M., Rehn, E., Linnenlucke, L., Munack, H., Wood, R., Petchey, F., Codilean, A. T., Jacobs, Z., Cohen, T. J., Williams, A. N., and Ulm, S.: SahulArch: A geochronological database for the archaeology of Sahul, Australian Archaeology, 89, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2022.2159751, 2023. a

Schaefer, J. M., Codilean, A. T., Willenbring, J. K., Lu, Z.-T., Keisling, B., Fülöp, R.-H., and Val, P.: Cosmogenic nuclide techniques, Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00096-9, 2022. a, b

Sternai, P., Sue, C., Husson, L., Serpelloni, E., Becker, T. W., Willett, S. D., Faccenna, C., Giulio, A. D., Spada, G., Jolivet, L., Valla, P., Petit, C., Nocquet, J.-M., Walpersdorf, A., and Castelltort, S.: Present-day uplift of the European Alps: Evaluating mechanisms and models of their relative contributions, Earth-Sci. Rev., 190, 589–604, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.01.005, 2019. a

Stone, J. O.: Air pressure and cosmogenic isotope production, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 105, 23753–23759, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JB900181, 2000. a, b

Stübner, K., Balco, G., and Schmeisser, N.: RIVERSAND: A new tool for efficient computation of catchmentwide erosion rates, Radiocarbon, 66, 2022–2035, https://doi.org/10.1017/rdc.2023.74, 2023. a, b, c, d, e, f

Tooth, S. D.: Floodouts in Central Australia, in: Varieties of Fluvial Form, edited by: Miller, A. J. and Gupta, A., 219–247, Wiley & Sons, Chichester, ISBN 978-0-471-97351-5, 1999. a

Whipple, K., Adams, B., Forte, A., and Hodges, K.: Eroding the Himalaya: Topographic and Climatic Control of Erosion Rates and Implications for Tectonics, J. Geol., 131, 265–288, https://doi.org/10.1086/731260, 2023. a

Wilner, J. A., Nordin, B. J., Getraer, A., Gregoire, R. M., Krishna, M., Li, J., Pickell, D. J., Rogers, E. R., McDannell, K. T., Palucis, M. C., and Keller, C. B.: Limits to timescale dependence in erosion rates: Quantifying glacial and fluvial erosion across timescales, Sci. Adv., 10, eadr2009, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adr2009, 2024. a

Zondervan, J. R., Hilton, R. G., Dellinger, M., Clubb, F. J., Roylands, T., and Ogrič, M.: Rock organic carbon oxidation CO2 release offsets silicate weathering sink, Nature, 623, 329–333, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06581-9, 2023. a

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The updated CRN Denudation collections

- Interoperability with online calculators

- Present-day glacier coverage and inferred denudation rates

- Limitations

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The updated CRN Denudation collections

- Interoperability with online calculators

- Present-day glacier coverage and inferred denudation rates

- Limitations

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References