the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The μDose system: determination of environmental dose rates by combined alpha and beta counting – performance tests and practical experiences

Thomas Kolb

Konrad Tudyka

Annette Kadereit

Johanna Lomax

Grzegorz Poręba

Anja Zander

Lars Zipf

Markus Fuchs

The μDose system is a recently developed analytical instrument applying a combined α- and β-sensitive scintillation technique for determining the radioactivity arising from the decay chains of 235U, 238U and 232Th as well as from the decay of 40K. The device was designed to meet the particular requirements of trapped charge dating methods and allows the assessment of environmental (i.e. low) levels of natural radionuclides. The μDose system was developed as a piece of low-cost laboratory equipment, but a systematic test of its performance is still pending. For the first time, we present results from a comprehensive performance test based on an inter-laboratory comparison. We compare the results obtained with μDose measurements with those from thick source alpha counting (TSAC), inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) and low-level high-resolution gamma spectrometry (HRGS) applied in five participating laboratories. In addition, the reproducibility and accuracy of μDose measurements were tested on certified reference materials distributed by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA; RGU-1, RGTh-1 and RGK-1) and on two loess standards (Nussy and Volkegem) frequently used in trapped charge dating studies. We compare μDose-based results for a total of 47 sediment samples with results previously obtained for these materials by well-established methods of dose rate determination. The investigated natural samples cover a great variety of environments, including fluvial, aeolian, littoral, colluvial and (geo-)archaeological sites originating from high and low mountain regions as well as from lowlands in tropical areas, drylands and mid-latitude zones of Europe, Africa, Australia, Central Asia and the Americas. Our results suggest the μDose system's capability of assessing low-level radionuclide contents with very good accuracy and precision comparable to well-established dosimetry methods. Based on the results of our comparative study and with respect to the practical experiences gained so far, the μDose system appears to be a promising tool for trapped charge dating studies.

- Article

(6758 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Over the last 2 decades, trapped charge dating techniques have become commonly applied standard tools for age determination of sediments in palaeo-environmental and geo-archaeological research. The vast arsenal of luminescence and electron spin resonance (ESR) dating methods (e.g. Bateman, 2019; Grün, 1989; Preusser et al., 2008) allows the direct dating of sedimentation processes, heating events and for ESR the precipitation of minerals. Ages obtained with trapped charge dating are derived from doses (energy per mass unit) stored by minerals such as quartz and feldspars, which are ubiquitously present in natural sediments and other materials such as tooth enamels and ceramics. These minerals may therefore be used as dosimeters. The dating events are associated with processes which involve the energetic stimulation of these minerals either by sunlight exposure (e.g. during sediment transport) or by natural or artificial heating (e.g. rocks fritted during volcanic eruptions; ceramics heated in kilns). The optical or thermal stimulation releases the dose previously stored within the crystal lattices of the involved dosimeters, thus “zeroing” the “luminescence clock” (e.g. Bateman, 2019; Wagner, 1998). When the minerals are no longer stimulated (e.g. after sediment deposition or after the end of the heating event), they remain exposed to the natural ionizing radiation arising from both cosmic radiation and the radioactive decay of members of the 238U, 235U and 232Th decay chains as well as from the decay of 40K in the surrounding sediments. This ongoing exposure to ionizing radiation results in a time-dependent accumulation of radiation doses within the minerals (e.g. Preusser et al., 2008). The total amount of dose absorbed under natural conditions since the last stimulation event is termed the palaeodose and can be determined in the laboratory by means of luminescence or ESR measurements based on a comparison with a corresponding amount of artificially administered (usually mono-energetic β or γ) dose, which is called the equivalent dose. ESR and luminescence ages are derived from this palaeodose and the total environmental dose rate. The dose rate describes the location-specific strength of natural ionizing radiation per time and is formally defined as the rate at which energy is absorbed by a dosimeter from the flux of radiation to which the dosimeter is exposed (e.g. Aitken, 1998).

While the cosmic component of the environmental dose rate is typically derived from information on the exact sampling position by applying well-established formulas (e.g. Prescott and Hutton, 1994), the contribution of ionizing radiation arising from the surrounding sediments is calculated by determining the activity concentrations of the relevant natural radionuclides. For dose rate determination, several in situ procedures using either portable gamma spectrometers or sensitive dosimeters such as BeO or Al2O3 have been developed. Additionally, laboratory analyses of bulk material are applied, including emission counting methods such as thick source alpha counting (TSAC; e.g. Turner et al., 1958) and beta counting (e.g. Sanderson, 1988), spectrometric approaches like low-level high-resolution gamma spectrometry (HRGS) and neutron activation analysis (NAA), and geochemical techniques such as inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES).

Recently, a laboratory-based, combined α and β particle detection instrument called the μDose system has been developed (e.g. Miłosz et al., 2017; Tudyka et al., 2018). Providing a cost-efficient approach, this novel device allows the determination of radionuclide concentrations of 238U, 235U, 232Th and 40K. Up to now, this measurement system has not been tested systematically. Therefore, we present a performance test based on three μDose devices and compare the results obtained with the new approach with those from established analytical techniques. The comprehensive study includes measurements on a total of ∼ 50 samples, covering natural samples as well as IAEA standards, and involves five different laboratories. In addition, we provide recommendations for sample handling and data analysis for the μDose results derived from practical experiences so far in the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory.

2.1 Technical description

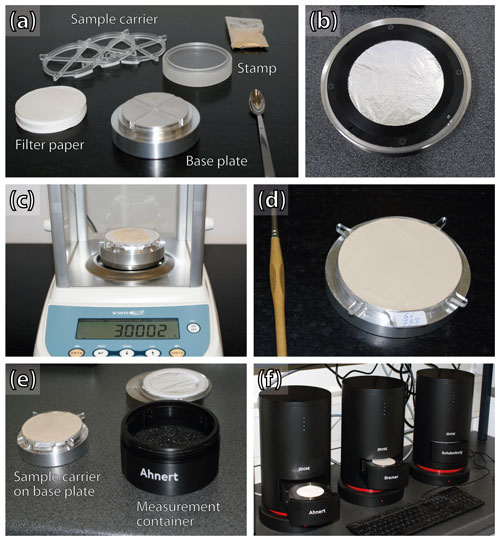

The μDose system (Fig. 1) is a compact and easy-to-handle analytical instrument allowing the simultaneous detection of α and β particles. For this purpose, the system is equipped with a dual-layer scintillator (Fig. 1b) consisting of a plate of β-sensitive (synthetic) material, which is coated with a thin film of ZnS:Ag for detecting α particles. This dual-layer scintillator is part of the cover plate of the sample container and is thus placed between the sample material and the photomultiplier. Since the scintillator does not have direct contact with the sample material under investigation and is additionally protected by an approximately 0.2 µm thin silver foil, the scintillator is reusable. In addition, this silver foil reflects photons emitted by the scintillators, which increases photon counting efficiency and guarantees an equal level of efficiency independent of the respective sample material. For measurements, the sample material is placed on a thin disc of filter paper, which is stored in a gas-tight sample container (Fig. 1e). The diameter of the disc matches the diameter of the photomultiplier tube (PMT), which may vary from 30 to 70 mm. For the present study, a PMT with a diameter of 70 mm was used. A detailed description of the technical setup is given by Tudyka et al. (2018).

Figure 1Photos showing the μDose devices and equipment: (a) sample carrier and equipment for sample preparation. (b) Scintillator unit with silver foil. (c) High-precision balance used for weighing 3.00 g of sample material. (d) Prepared sample on a sample carrier with a diameter of 70 mm. (e) Prepared sample material and measurement container. (f) Three μDose devices installed in the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory.

α and β particles are discriminated based on the different shapes of the pulses induced by the particles. Amplified by the PMT, these pulses are identified and analysed by a pulse analyser unit that has previously been described in detail by Miłosz et al. (2017). During the measurement process, an analogue-to-digital converter (ADC) samples and transforms the incoming pulses into digital values (ADC values). These ADC values are time-stamped and stored in a database. Thus, a re-evaluation of data is possible at any time without the need to repeat the measurement. Data analyses are performed by applying a special algorithm. This algorithm determines pulse height and pulse shape of the stored pulses, allowing the discrimination between α- and β-induced pulses as well as the elimination of background pulses caused by interfering variables. Data analysis is possible after finishing the measurement as well as during a still running measurement process.

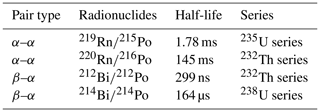

The μDose system is not only capable of discriminating between α and β particles, but also allows the detection of decay pairs. Such decay pairs arise from the fast succession of two decays and thus two incoming pulses (pairs) detected within a very short and specific period of time. These pairs are the result of short half-lives of some members of the involved decay chains. This principle has long been used in TSAC to derive the particular contributions from the uranium and thorium series (e.g. Aitken, 1985). Whereas the TSAC technique is restricted to α–α pairs, the μDose system is also able to make use of β–α pairs, which can be identified based on the individual time stamp of each detected pulse. Thus, the determination of the activities arising from the 238U, 235U and 232Th series as well as from the decay of 40K is based on two α–α pairs and two β–α pairs. A summary is given in Table 1. One α–α pair is part of the 235U series and caused by the successive α decays of 219Rn and 215Po, with the latter showing a half-life of 1.78 ms. With (half-life of 216Po: 145 ms) a second α–α pair is part of the 232Th series. One β–α pair arises from the successive decay of 212Bi and 212Po, which has a half-life of only 299 ns. Finally, the β decay of 214Po (half-life: 164 µs) following an α decay of 214Bi is a characteristic component of the 238U series. On the condition that the investigated sample is in or at least close to secular equilibrium, the α and β counts associated with the above-mentioned decay pairs allow for the calculation of the concentrations of 238U, 235U and 232Th and thus provide the possibility to derive the series-specific activities. The particular 40K activity is determined as a residual value derived from the excess of observed β counts over the β counts expected to arise from the determined 238U, 235U and 232Th series. For details on how decay pairs are statistically identified and for a thorough description of formulas and assumptions used for calculating the specific contributions arising from the different decay series, the reader is referred to Tudyka et al. (2018).

2.2 System calibration

Since the activities are derived from the net count rates of the detected decay pairs using equations for which pair-specific calibration parameters are needed (see Tudyka et al., 2018), these parameters have to be determined for each μDose device by performing calibration measurements on material of known activities. The μDose systems can be calibrated for different amounts of sample material using calibration material distributed by the manufacturer.

For the calibration of the μDose systems at the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, three standards prepared on behalf of the IAEA are used, i.e. IAEA-RGU-1, IAEA-RGTh-1 and IAEA-RGK-1 (hereafter always mentioned as RGU-1, RGTh-1 and RGK-1). For a detailed description of the calibration material, see Sect. 3.1 of this article. Moreover, a device- and location-specific background value has to be determined using a background disc placed on the sample holder. Since all three calibration materials have high activities, the respective calibration measurements were performed for only 24 h. For the background determination, a longer-lasting measurement of 7 d was executed. In order to increase the accuracy of the calibration, we advise using repeated measurements of all standards and deriving the calibration parameters from the means of these repeated measurements. This will substantially reduce the impact of random errors potentially affecting single measurements. In the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, the means of three repeated measurements for each standard and one background measurement are combined to define the device-specific calibration. Comprising 10 separate measurements (3 × 3 IAEA standards + 1 background measurement), the whole calibration procedure requires a total duration of ∼ 14 d. The μDose software offers a user-friendly calibration module to define and manage calibrations.

Since raw data from finished measurements (i.e. the ADC coded pulses) are stored in a database, data evaluation can be performed at any time using different calibration settings. This allows re-calculating the determined activities without the need for conducting another time-consuming measurement. Furthermore, this database solution provides the opportunity to identify significant changes in the technical specifications of the devices.

Although there were no such significant changes detected so far during the ∼ 1.5 years of μDose usage in the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, such changes seem possible and might predominantly be attributed to various ageing effects. These ageing effects may affect the silver foil used, the dual-layer scintillator or other electronic components of the devices, in particular the efficiency of the built-in PMTs. Thus, we strongly recommend a re-calibration of the μDose systems at regular intervals in order to guarantee that the determined calibration parameters still match the actual technical status of the measurement setup. In the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, a re-calibration of the μDose systems is performed twice a year with time intervals of no more than 6 to 8 months. This re-calibration is based not only on an isolated measurement of a specific test sample, but also comprises the whole calibration procedure as described above, including nine separate measurements of IAEA standards as well as a prolonged measurement of the device-specific background signal.

2.3 Determination of uncertainties

The μDose system considers several sources of uncertainties that are associated either with the measurement procedure or with the sample preparation. The most dominant uncertainties are derived from the counting statistics of calibration measurements (here IAEA standards and background) and investigated samples. Additionally, there is a relative counting rate uncertainty of 0.001 that corresponds to sample preparation reproducibility or other unknown sources of error. This component of uncertainty will not decrease with increasing measurement time. The μDose system allows adjusting the (recommended) default values for each device by user-specified values. Uncertainty propagation considers correlations between the individual uncertainties determined for the different radionuclide activities and/or concentrations. A detailed description of the mode of uncertainty propagation used for μDose analysis is provided by Tudyka et al. (2020).

3.1 IAEA standards

Provided by the IAEA, RGU-1, RGTh-1 and RGK-1 standards were used not only as calibration material for the μDose systems (see above) but also for performance tests validating the quality of calibration. The RGU-1 and RGTh-1 standards were both prepared by the Canada Centre for Mineral and Energy Technology. The standards were derived from a uranium ore (BL-5) and a thorium ore (OKA-2), respectively. These raw materials were diluted with floated silica powder of negligible uranium and thorium contents. For both raw materials, the IAEA was able to show them to be in radioactive equilibrium (for details see IAEA, 1987).

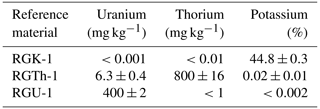

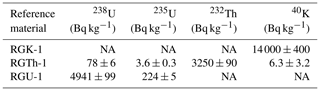

The IAEA certifies the radionuclide concentrations as follows: 400±2 mg kg−1 uranium, <1 mg kg−1 thorium and <0.002 % potassium for the RGU-1 standard; 6.3±0.4 mg kg−1 uranium, 800±16 mg kg−1 thorium and 0.02±0.01 % potassium for the RGTh-1 standard (IAEA, 1987). For RGU-1, these concentrations correspond to radioactivity values of 4941±99 Bq kg−1 for 238U, 224±5 Bq kg−1 for 235U and negligible values for 232Th as well as for 40K. For RGTh-1, the IAEA gives values of 3250 Bq kg−1 (95 % confidence interval – CI: 3160–3340 Bq kg−1) for 232Th, 3.6 Bq kg−1 (95 % CI: 3.3–3.9 Bq kg−1) for 235U, 78 Bq kg−1 (95 % CI: 72–84 Bq kg−1) for 238U and 6.3 Bq kg−1 (95 % CI: 3.1–9.5 Bq kg−1) for 40K (see data sheet on the IAEA home page). All values are summarized in Table 2 (concentrations) and Table 3 (activities).

Table 2Radionuclide concentrations as certified by the IAEA (IAEA, 1987). Uranium and thorium values are given in milligrams per kilogram (mg kg−1), and potassium is given in percent. Uncertainties represent the 95 % CI.

Table 3Recommended radionuclide-specific activities as provided on the home page of the IAEA. All values are given in becquerels per kilogram (Bq kg−1). Please note that only values for which information is provided by the IAEA were considered for this table. Uncertainties represent the 95 % CI.

The RGK-1 standard was derived from high-purity potassium sulfate supplied and certified under the label Extra Pure DAC by the Merck Company. Based on repeated measurements applying atomic absorption spectrometry, the potassium content was determined by the IAEA Laboratories Seibersdorf, which also estimated values for the uranium and thorium content (for details see IAEA, 1987). The RGK-1 standard reveals a 40K activity of 14 000 Bq kg−1 (95 % CI: 13 600–14 400 Bq kg−1), showing negligible concentrations of thorium (<0.01 mg kg−1) and uranium (< 0.001 mg kg−1).

3.2 Nussy loess standard

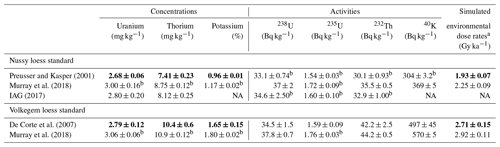

The Nussy reference material is a loess sample from a well-known loess section near Nußloch (e.g. Antoine et al., 2001; Bente and Löscher, 1987; Sabelberg and Löscher, 1978) located ∼ 10 km south of the city of Heidelberg, at the eastern shoulder of the Upper Rhine Graben, Germany (49∘19′ N, 8∘43′ E; 217 m a.s.l.). Here, loess sediments revealing a total thickness of ∼ 16 m are covering a basement of Middle Triassic limestone and dolomite formations. The sample was collected from the upper Weichselian loess deposits accumulated during the last glacial–interglacial cycle. The Nussy sample reveals grain sizes characteristic for loess sediments, ranging from 2–63 µm. The material was first used as a reference material in the Heidelberg Luminescence Laboratory (e.g. Kalchgruber, 2002; Rieser, 1991) and prepared as the first certified reference material (CRM) for loess by Kasper et al. (2001). Based on an inter-laboratory comparison with contributions from three different laboratories, Preusser and Kasper (2001) provided the following concentrations, which were derived from the average of 11 HRGS measurements: 2.68±0.06 mg kg−1 (SD: 0.09 mg kg−1) for the total U content, 7.41±0.23 mg kg−1 (SD: 0.34 mg kg−1) for Th and 0.96±0.01 % (SD: 0.02 %) for K. Later, these values were re-evaluated: based on geochemical analyses involving over 50 laboratories, the International Association of Geoanalysts (IAG) characterized the Nussy loess as reference material IAG UoK Loess, reporting radionuclide concentrations of 2.80±0.20 mg kg−1 (2σ) for U and 8.12±0.25 mg kg−1 (2σ) for Th (for details see IAG, 2017). The IAG did not determine the potassium content. Most recently, Murray et al. (2018) re-investigated the Nussy loess standard applying HRGS. They reported activities of 37±2 Bq kg−1 for 238U, 35.5±0.5 Bq kg−1 for 232Th and 369±5 Bq kg−1 for 40K. For our study, we refer to the values published by Preusser and Kasper (2001). All values are summarized in Table 4.

Preusser and Kasper (2001)Murray et al. (2018)IAG (2017)De Corte et al. (2007)Murray et al. (2018)Table 4Summary of concentrations and activities published for the Nussy and Volkegem loess standards. Values used as reference values for this study are highlighted as bold numbers. The errors for these values represent 95 % CIs. Please note: for better comparison, the standard deviations (SDs) given by Preusser and Kasper (2001) were translated to 95 % CI values in this table and in the text by applying a t distribution with 10 degrees of freedom. Concentration and activity values not provided by the original publications were re-calculated for this table and are flagged by b symbols (for details see table notes). Simulated environmental dose rates based on assumed constant values for water content and cosmic radiation were derived from the radionuclide concentrations in this table (for details see table notes).

a Values in this column represent simulated environmental dose rates calculated for the 90–200 µm grain size fraction of HF-etched quartz using the Dose Rate and Age Calculator

DRAC v1.2 (Durcan et al., 2015). All calculations are based on the radionuclide concentrations provided in this table, applying the dose rate conversion factors given by

Guérin et al. (2011). Please note that a constant water content of 15±5 % and a constant contribution of 0.150±0.015 Gy ka−1 arising from cosmic radiation were assumed for

all calculations. We would like to point out that these assumed values do not correspond to the values that might actually be determined for Nussy and Volkegem sampling sites.

Therefore, the calculated dose rates are referred to as “simulated environmental dose rates” in the table and in the text.

b Values converted from radionuclide concentrations to

activities and vice versa were calculated using conversion factors and natural uranium composition given by Guérin et al. (2011). All calculations were verified by applying the

radionuclide-specific conversion factors provided in Table 2.5 of IAEA (2003).

3.3 Volkegem loess standard

The Volkegem reference material is a loess sample collected in a former quarry in the city of Volkegem (East Flanders, Belgium). Originally, the reference material was characterized in a comprehensive study by De Corte et al. (2007). After drying at 110 ∘C and milling, the sample material was sieved to grain diameters <50 µm and homogenized. This material was investigated by applying k0 INAA and HPGe gamma spectrometry and additionally cross-checked by in situ gamma spectrometry, TSAC, and Geiger–Muller beta counting (for a detailed description see De Corte et al., 2007). As reference data, they were able to determine mean radionuclide concentrations of 2.79±0.12 mg kg−1 for U, 10.4±0.6 mg kg−1 for Th and 1.65±0.15 % for K as well as mean activities of 36.1±1.7 Bq kg−1 for 235+238U, 42.2±2.5 Bq kg−1 for 232Th and 497±45 Bq kg−1 for 40K. Like the Nussy reference material, Murray et al. (2018) also re-investigated the Volkegem standard. They report slightly higher activities of 37.8±0.7 Bq kg−1 for 238U, 44.2±0.5 Bq kg−1 for 232Th and 570±5 Bq kg−1 for 40K. For our study, we refer to the original values published by De Corte et al. (2007). All values are summarized in Table 4.

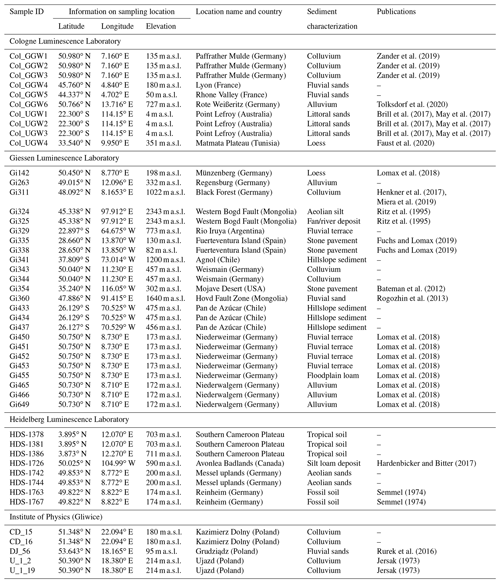

3.4 Natural samples

For this study, 47 natural samples covering a great variety of environmental settings and landscapes were analysed in order to validate the performance of μDose measurements. The samples were provided by and measured in five laboratories in Germany and Poland, including the luminescence laboratories at the universities of Bayreuth, Cologne, Giessen and Heidelberg as well as the Institute of Physics in Gliwice. All analysed samples are summarized in Table B1 in Appendix B. A detailed description of sampling locations including geological, stratigraphic and morphological settings is provided in Appendix C.

4.1 Sample preparation

All analysed samples were dried in a drying chamber at an elevated temperature of 105 ∘C for several days. The dried sample material was gently crushed using a porcelain mortar and then homogenized. Approximately 10 g of this homogenized material was pulverized in a ball mill (Retsch M 400) using a frequency of 29.5 Hz for 45 min and dry-sieved with analytical sieves showing mesh sizes of 63 µm. This sieving procedure is used as an additional backstop in the sample preparation, which is based on the idea that coarse-grained residuals of >63 µm indicate that the applied milling duration was not sufficient to provide fully pulverized material. Thus, the sieving step is not used to exclude resilient grains with diameters >63 µm, since this would cause a mineral-specific fractionation and introduce bias to the μDose measurements. The additional sieving step merely aims at surveying the quality of the preparation procedure applied in the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory. With respect to the samples investigated in this study, we were not able to detect any residual material >63 µm. Therefore, we conclude that the applied milling duration of 45 min was sufficient to provide pulverized material adequate for μDose measurements.

After weighing 3.00 g of this pulverized material with a high-precision balance (Fig. 1c), the sample material was placed on a sample carrier and carefully fixed on top of a disc of filter paper using a stamp made of acrylic glass (Fig. 1a and d). The discs show diameters matching the diameters of the PMTs used (here 70 mm). For the measurement procedure, the filled sample carriers were stored in a device-specific, gas-tight measurement container (Fig. 1e) which prevents migration of radon from and into the container.

Additionally, the bottom of the measurement container is filled with granular active carbon, which contributes to reducing the radon concentration of the air within the container. This aims at avoiding an accumulation of radon gas right in front of the scintillator module, which may impact the alpha count rate.

4.2 Technical settings for the μDose devices

All measurements have been performed on μDose devices installed in the Luminescence Laboratory of the Department of Geography at the Justus Liebig University Giessen. The devices are situated in a laboratory that is exclusively designated for sedimentological analyses and for the preparation of dose rate samples. Thus, neither luminescence measurement systems with their integrated radioactive sources nor other technical devices that might generate radiation fields or electromagnetic fields had any kind of potentially distracting impact on the μDose measurements.

Three measurement systems with identical technical features are installed – named “005-Ahnert”, “006-Bremer” and “007-Rohdenburg” (Fig. 1f). All devices are equipped with internal high-voltage power supplies and photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) that have a photocathode diameter of 70 mm. The measurement units are controlled by a single PC with distinct, system-specific measurement software. Measurement data are primarily stored on the built-in SSD drive of this PC and additionally saved on backup servers provided by the Department of Geography. A device-specific unique measurement ID is assigned for each measurement.

The μDose systems at the Giessen laboratory are calibrated for a total amount of 3 g of sample material. In order to guarantee that all investigated samples matched this specification, the samples were checked using a high-precision balance prior to the measurements. Only samples lying within a range of 2.995 to 3.005 g were accepted for measurement.

In order to minimize the possible bias of α counts due to the adhesion of radon-bearing particles from ambient air, a delayed start of the measurement procedure is advised. In the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, the applied time delay was at least 1 h; i.e. after storing the sample in the measurement container and sealing it, the operator has to wait for at least 1 h before initiating the start of the measurement procedure. For ease of use, upcoming versions of the μDose software will provide the possibility to define an automated and user-specified time delay.

The respective measurement times strongly depended on the sample-specific activities. For the experiment analysing the impact of measurement duration (see Sect. 4.3.2), various measurement times were applied. Due to their high activities, relatively short measurement times of ∼ 24 h were used for the IAEA standards RGU-1, RGTh-1 and RGK-1, yielding excellent counting statistics. For the remaining samples, including both loess standards and natural samples, measurements were continued until the number of detected α counts reached the level of approximately 3000 counts, an empirically determined threshold that was derived from long-lasting experiences with TSAC at the University of Bayreuth (Ludwig Zöller, personal communication, 2020). Depending on the respective activities of a sample, this value corresponds to measurement durations of 2–4 d for samples revealing average environmental dose rates in the range of 2 to 4 Gy ka−1.

4.3 Experimental setups

For this study, a total of three different experiments were conducted, which aimed at assessing the performance and reliability of the μDose systems.

4.3.1 Accuracy and reproducibility of results

A first experimental setting aimed at assessing the reproducibility and accuracy of measurement results obtained with the μDose systems. Therefore, repeated measurements were performed on the certified IAEA standards and on the two loess standards. For these measurements, one 3 g subsample of each standard was prepared. These subsamples were used for all measurements on all devices. So, there was no re-sampling. Once stored in the device-specific measurement container, the subsamples were not removed from the container until all measurements on the respective device were completed. Measurements for the IAEA standards were restricted to ∼ 24 h, while the loess standards were each measured for approximately 4–5 d. Measurements have been performed on all three devices.

4.3.2 The impact of the measurement duration

The measurement duration required for a reliable result might be a crucial point since accuracy and precision of the μDose measurements strongly depend on the net count rates of α and β particles. In TSAC, device-specific numbers of α counts are often used as thresholds to ensure count rates that enable the calculation of radionuclide concentrations with a sufficiently high precision. As already mentioned above, a value of approximately 3000 α counts is routinely used in the Giessen laboratory to guarantee reliable results. However, this value is merely an arbitrary threshold, which is derived from long-lasting experiences with TSAC in the luminescence laboratory at the University of Bayreuth (Ludwig Zöller, personal communication, 2020). With particular respect to environmental samples revealing low radionuclide concentrations the usage of such a high threshold may lead to prolonged measurement times that would not be desirable for routine dose rate measurements. In the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory for instance, several samples originating from the Negev desert (Israel) were measured, for which dose rates of <1 Gy ka−1 could be determined. Applying the 3000 α count criterion, each sample had to be measured for more than 15 d.

In order to investigate the impact of measurement duration and to test whether shorter measurement times also provide reliable results, 3 g subsamples of both loess standards (Nussy and Volkegem) were repeatedly measured by applying various measurement times. The measurement times lasted from a minimum of approximately 10 h to more than 7 d, corresponding to total α counts of ∼ 200 to more than 8000. All measurements were performed as stand-alone measurements; i.e. the results for short- and medium-time measurements were calculated from numerous separate measurements and not derived from one long-lasting master measurement. Both subsamples were measured on all three μDose systems. Once stored in the measurement container, the subsamples were not removed from the container until all measurements were finished for the respective device. For all measurements, the same subsamples of Nussy and Volkegem loess standards were used.

4.3.3 Comparison to established measurement procedures

In order to test the overall performance of the μDose system, we initiated a comprehensive inter-laboratory comparison including five different laboratories from Germany and Poland, which applied different measurement procedures. The involved laboratories were (i) the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, (ii) the Bayreuth Luminescence Laboratory, (iii) the Cologne Luminescence Laboratory, (iv) the Heidelberg Luminescence Laboratory and (v) the Institute of Physics (Division of Geochronology and Environmental Isotopes) in Gliwice.

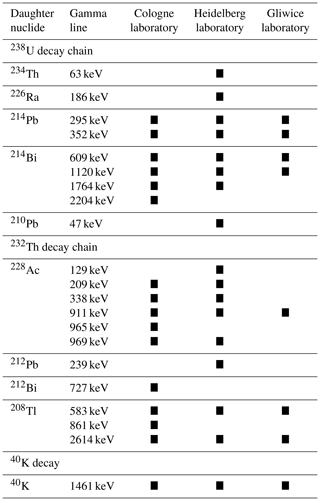

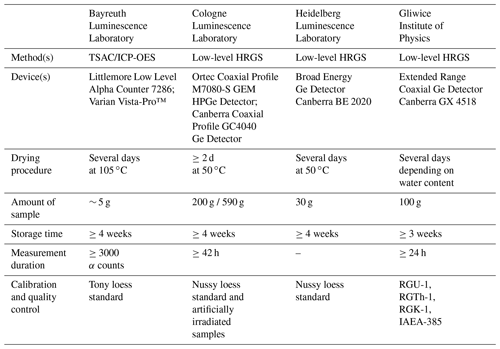

Table 5Summary of measurement settings in the participating laboratories. Details of sample preparation and applied measurement procedures are described in the text and in Appendix A.

For this performance test, we re-investigated a total of 47 environmental samples for which either radionuclide concentrations or activities had already been determined by either TSAC in combination with ICP-OES (Bayreuth) or low-level HRGS (Cologne, Heidelberg, Gliwice). Details on sample preparation and technical specifications of the μDose systems in Giessen are provided in Sect. 4.1 and 4.2. The measurement configurations applied in the other participating laboratories are briefly summarized in Table 5. Details of sample preparation and information on the applied measurement procedures including gamma lines used are provided in Appendix A. The investigated samples represent a broad variety of regions and environmental settings (see Table B1 and sample characterization in the Appendix).

5.1 Accuracy and reproducibility of measurement results

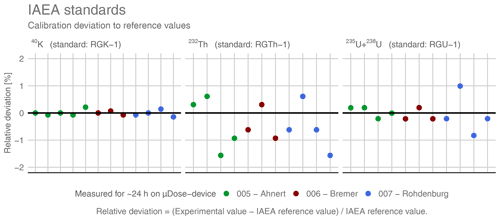

The accuracy and reproducibility of measurement results were tested by repeated measurements of three certified IAEA standards that had also been used for the calibrations of the μDose devices. Due to their high radionuclide concentrations these standards provide high decay rates, improving the statistics of α and β counts. Figure 2 shows the results of repeated measurements of these standards expressed as relative deviations of measured results from the expected reference values provided by the IAEA. For the plot, only the results obtained for the dominant radioactive emitter of the respective standard were considered. So, for RGK-1 only the activity of 40K, for RGTh-1 the activity of 232Th, and for the uranium standard RGU-1 the combined activities of 235U and 238U were analysed.

Figure 2Results for repeated measurements of the investigated IAEA standards. The different colours of the symbols represent three different measurement devices (see legend). All plots show the relative deviation of measured values from the respective reference values provided for the IAEA standards. Sample RGK-1 is illustrated on the left, the thorium standard RGTh-1 is shown in the centre and RGU-1 is depicted on the right. Bold lines illustrate the 0 % deviation (i.e. perfect agreement of measured and expected values). Please note that only activities arising from the dominant radioactive emitter of the respective standard were considered for this figure.

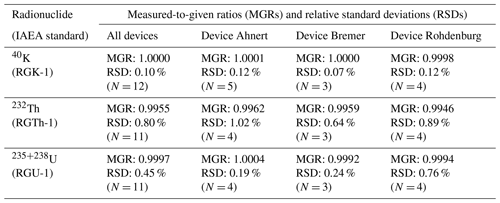

Table 6Accuracy and precision of μDose measurements of certified IAEA standards. The accuracy is expressed as measured-to-given ratios (MGRs). Precision is given as relative standard deviation (RSD) of measured activities. Only results derived for the dominant emitter of the respective IAEA standard were considered for this table.

From the results shown in Fig. 2 we are able to draw two important conclusions: (i) μDose measurements of IAEA standards reveal excellent accuracy. For potassium, thorium and uranium, all measured values are within the respective 95 % confidence intervals certified by the IAEA. The majority of relative deviations of measured activities from the certified values are <1 %. The mean relative calibration deviations are −0.0001 % for 40K, −0.4554 % for 232Th and −0.0298 % for 235+238U. These values correspond to measured-to-given ratios of 1.0000 for 40K, 0.9955 for 232Th and 0.9997 for 235+238U and indicate excellent quality of the implemented μDose calibrations. (ii) The repeated measurements of IAEA standards are characterized by excellent reproducibility. The determined results reveal neither statistically significant outliers nor distinct differences between the different measurement devices. The relative standard deviations (RSDs) obtained from statistics and averaged for all devices are 0.10 % for 40K, 0.80 % for 232Th and 0.45 % for 235+238U. An overview summarizing accuracy and statistical reproducibility is provided in Table 6.

These results may be attributed to the high content of radionuclides characteristic for the investigated IAEA standards. Although only measured for ∼ 24 h, the net α counts detected for RGU-1 and RGTh-1 show mean values of ∼ 46 000 and ∼ 30 000 cts, respectively. These total numbers of α counts are more than 10 times higher than the threshold value of 3000 α counts typically applied in the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory for μDose measurements of sediment samples. In summary, these results indicate the excellent quality of μDose calibration and good reproducibility of measurements.

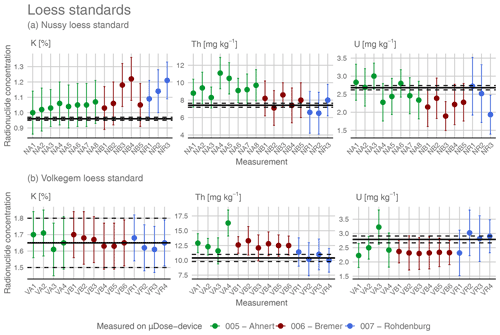

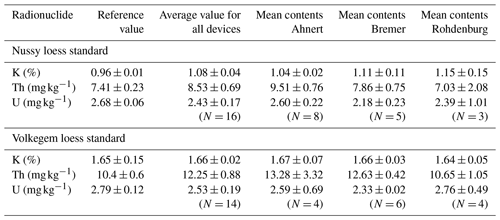

Figure 3Results from repeated μDose measurements for the loess standards Nussy (a) and Volkegem (b). The different colours of the symbols represent three different measurement devices (see legend). All plots show radionuclide concentrations either in milligrams per kilogram (mg kg−1) (U and Th) or in percent (K). Please note that the bold reference lines indicate radionuclide contents originally published for the Nussy loess standard by Preusser and Kasper (2001) and for the Volkegem loess standard by De Corte et al. (2007). Dashed lines characterize the corresponding 95 % CI. Error bars indicate measurement uncertainties on the 2σ level.

Table 7Results from μDose measurements and reference values for K, Th and U contents of Nussy loess standard (upper part) and Volkegem loess standard (lower part). The values for K are given in percent, the values for U and Th are given in milligrams per kilogram (mg kg−1). Reference values (and their associated 95 % CIs) are according to Preusser and Kasper (2001) and De Corte et al. (2007). The 95 % CIs for Nussy have been re-calculated based on the SD values provided by Preusser and Kasper (2001). Uncertainties of the μDose measurements correspond to 95 % CIs. The table shows mean values for individual μDose devices as well as average values calculated as a mean of all measurements on the three devices.

Figure 3 shows the accuracy and reproducibility of results obtained for the two loess standards Nussy (Preusser and Kasper, 2001) and Volkegem (De Corte et al., 2007). All measured values are summarized in Table 7. For the Nussy standard, the mean values of the determined concentrations averaged over all three devices are 1.08 % (SD: 0.07 %) for potassium, 8.53 mg kg−1 (SD: 1.30 mg kg−1) for thorium and 2.43 mg kg−1 (SD: 0.32 mg kg−1) for uranium. These values correspond to mean measured-to-given ratios of 1.13 for potassium, 1.15 for thorium and 0.91 for uranium.

For the Volkegem loess standard, the averaged values of all μDose measurements are as follows: 1.66 % (SD: 0.03 %) for potassium, 12.25 mg kg−1 (SD: 1.53 mg kg−1) for thorium and 2.53 mg kg−1 (SD: 0.32 mg kg−1) for uranium. The corresponding measured-to-given ratios are 1.00 for potassium, 1.18 for thorium and 0.91 for uranium.

For both samples, the uranium contents are slightly underestimated by ∼ 10 %, whereas thorium contents are overestimated by ∼ 15 % and ∼ 18 %, respectively. For the Nussy standard, potassium is also overestimated by ∼ 13 %, while there is nearly perfect agreement with the reference value for the Volkegem standard.

At first glance, the results obtained for the loess standards seem to indicate some kind of problem concerning the accuracy of the μDose measurements. In order to check this and to assess intra-sample variability, we re-sampled and re-measured both loess standards. The results of these additional measurements did not significantly differ from the results reported in this study and showed similar deviations of ∼ 9 % up to ∼ 17 %. However, when talking about deviations determined for specific radionuclides, it should be considered that uranium and thorium concentrations are not detected independently in μDose measurements (see Sect. 2.1). This dependency can clearly be seen when looking at the Th and U concentrations of the Volkegem loess standard in the lower part of Fig. 3. Whenever Th concentrations are higher than the expected value, the corresponding U concentration is lower and vice versa. For the Nussy loess standard, the results shown in the upper part of Fig. 3 are similar, but not as obvious as for the Volkegem loess standard. When deriving environmental dose rates, the exact ratio has some relevance. However, the conversion of alpha count rates to dose rates in TSAC shows that the conversion factor for the beta dose rate is higher for uranium and lower for thorium, while the conversion factor for the gamma contribution is higher for thorium and lower for uranium (e.g. Aitken, 1985). In the end, there is at least a partial compensation. As a result, the total environmental dose rate does not vary much with the exact ratio (e.g. Li and Tso, 1995). With respect to the determination of environmental dose rates, deviations in the individual concentrations and/or activities of uranium and thorium are acceptable as long as the combined activity arising from uranium and thorium is close to the expected value.

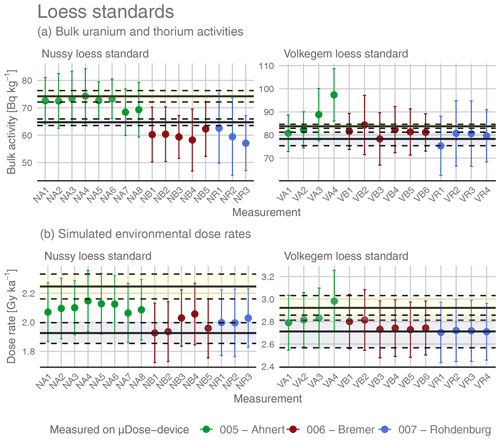

Figure 4Bulk uranium and thorium activities given in becquerels per kilogram (Bq kg−1) (a) and simulated environmental dose rates given in grays per thousand years (Gy ka−1) (b) for both investigated loess standards. The Nussy loess standard is depicted on the left, the Volkegem loess standard is shown on the right. The different colours of the symbols represent three different measurement devices (see legend). Please note that the bold reference lines centred within the grey area indicate radionuclide contents originally published for the Nussy loess standard by Preusser and Kasper (2001) and for the Volkegem loess standard by De Corte et al. (2007), whereas the bold lines centred within the yellow area represent benchmark values derived from the results published by Murray et al. (2018).

Figure 4a shows the combined activity arising from the uranium and thorium decay chains for the Nussy loess standard (left) and for the Volkegem loess standard (right). With respect to the latter, the values determined with the μDose system are in good agreement with the expected benchmark value published by De Corte et al. (2007). With individual measured-to-given ratios ranging from 0.96 (measurement VR1) to 1.24 (measurement VA4), the mean measured-to-given ratio averaged for all devices is 1.05. Revealing a relative standard deviation of ∼ 6 %, the spread in data is rather low, although the combined uranium and thorium activities determined for measurement VA3 and VA4 show rather large deviations. Based on the 3 IQR criterion these values can be characterized as extreme outliers. Not considering these values, the measured-to-given ratio for the Volkegem loess standard would average out at 1.03.

These overall good results are reflected by the calculated simulated environmental dose rates for the Volkegem loess standard, which is depicted on the right side of Fig. 4b. Based on the radionuclide concentrations published by De Corte et al. (2007), a value of 2.71±0.15 Gy ka−1 is expected. The simulated environmental dose rates calculated for the μDose results show a range from 2.70 to 2.98 Gy ka−1 and average at a value of 2.77±0.02 Gy ka−1, which corresponds to a mean measured-to-given ratio of 1.02. If the above-mentioned extreme outliers are not considered for data analysis, the average simulated dose rate for the remaining measurements is 2.75±0.01 Gy ka−1 and the measured-to-given ratio improves to 1.01. In summary, we can conclude that the μDose measurements are able to provide results that allow the calculation of simulated environmental dose rates that are in good agreement with the expected benchmark value for the Volkegem loess standard.

For the Nussy loess standard the results are less satisfying. With an average combined uranium and thorium activity of 66.01 Bq kg−1, the μDose measurements overestimate the benchmark of 64.74 Bq kg−1 derived from the values published by Preusser and Kasper (2001) by only ∼ 2 %. This would correspond to a promising overall measured-to-given ratio of 1.02. However, the bulk uranium and thorium values determined by the μDose measurements show a rather large relative standard deviation of ∼ 10 %. Furthermore, there are distinct inter-device differences reflected by pronounced variations in the device-specific mean measured-to-given ratios. These ratios range from 0.92 for the devices 006-Bremer and 007-Rohdenburg to 1.13 for device 005-Ahnert. While the first two devices underestimate the expected value, the latter shows a considerable overestimation.

When looking at the calculated simulated environmental dose rates, the results are slightly better than for the combined activities of uranium and thorium. The mean value averaged for all measurements is 2.04±0.02 Gy ka−1 and is slightly higher than the benchmark of 1.93±0.07 Gy ka−1. With device-specific measured-to-given ratios of 1.09 (Ahnert), 1.03 (Bremer) and 1.04 (Rohdenburg), the average measured-to-given ratio for all devices corresponds to 1.06. Except for the values of two μDose measurements, all simulated environmental dose rates are beyond the range of the 95 % confidence interval given for the benchmark of Preusser and Kasper (2001). But still, all simulated environmental dose rates are within the range of benchmarks calculated for the IAG values and for the values provided by Murray et al. (2018), which can clearly be seen on the left side of Fig. 4b.

For a meaningful interpretation of results it has to be considered that the published reference values were derived from a limited number of gamma spectrometry and k0 INAA measurements that were carried out under specific laboratory conditions. Therefore, they may suffer from distinct methodological problems. On closer inspection, it thus becomes apparent that inter-methodological deviations of more than 10 % are neither unusual for dosimetry measurements (e.g. Murray et al., 2015) nor necessarily indicate serious deficits in the respective measurement procedures. On contrary, the results obtained for the IAEA standards (see above) suggest good accuracy and reproducibility of μDose measurements.

A closer look at the publication of Preusser and Kasper (2001) shows that the authors provide not only results derived from HRGS, but also ICP-MS-based values from three different laboratories. The magnitude of scatter in the data reported for the Nussy loess standard is comparable to the maximum deviations determined for the μDose measurements. For the K content, values from 0.96 % to a maximum of 1.14 % are reported, while the Th and U contents range from 7.4 to 8.8 mg kg−1 and from 2.3 to 2.7 mg kg−1, respectively. Referring to the reference value for the Nussy loess standard, this spread in data corresponds to relative deviations of approximately 15 % to 19 %.

A smaller but still considerable spread in the determined data can be observed when the values published by Preusser and Kasper (2001) are compared to the IAG reference values for U and Th. Here, the IAG values exceed the originally published data by ∼ 5 % (U) and ∼ 10 % (Th).

A similar finding can be noticed for Volkegem loess activities given by De Corte et al. (2007) when compared to results derived from the re-measurements of Murray et al. (2018). For all radionuclides, Murray et al. (2018) reported substantially higher activities. While the 232Th activity exceeds the originally determined value by ∼ 5 %, the deviations for 238U and 40K are considerably more pronounced, revealing relative values of ∼ 10 % and ∼ 15 %, respectively.

5.2 Measurement time and associated alpha count rates

Dosimetry measurements can be time-consuming. This might either be caused by the need for extensive preparation procedures and long-lasting storage times or the measurement process itself. For the μDose system, sample preparation is relatively rapid and samples can be measured immediately after the preparation procedure without the need for storage for specific periods of time. Since accuracy and precision of μDose measurements strongly depend on the net alpha and beta count rates, the measurement duration is a decisive factor for the quality of the obtained results. In terms of net α and β counts, this becomes obvious when comparing the results obtained from the investigated IAEA standards (up to ∼ 30 000–46 000 α counts) to the results determined for the loess standards (up to ∼ 3000 α counts; see Sect. 5.1). In theory, longer measurement times will provide better counting statistics (i.e. higher numbers of α and β counts), which should improve both accuracy and precision of the results. From a theoretical point of view, long-lasting measurements should thus be favoured. However, it is obviously impossible to implement such an approach in practice since for typical environmental samples trying to reach count rates similar to those reported for the IAEA standards would mean having to accept long-lasting measurements of several weeks or even months.

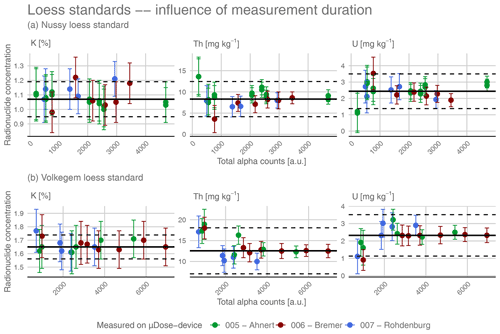

Figure 5Results from μDose measurements of two loess standards (Nussy – a; Volkegem – b). Values on the x axis represent the number of total α counts. The y-axis values give the respective radionuclide concentration either in percent (K) or in milligrams per kilogram (mg kg−1) (Th and U). The different colours of the symbols represent three different μDose devices (see legend). The bold lines illustrate the median values derived from the determined results. Dashed lines indicate the 2σ deviation.

Figure 5 shows the results of an experiment aiming at identifying whether there is a particular lower limit of measurement durations for which reliable results can still be expected. The plots show radionuclide concentrations (y axis) plotted against the total number of detected α counts (x axis). All measurements were conducted as separate stand-alone measurements on the same subsamples of the Nussy and Volkegem loess standards.

The majority of results cluster rather closely to the median values indicated by the bold lines. Overall, this seems to be true for all measurement durations. For the thorium and uranium contents of the Volkegem loess standard, short-time measurements with a total number of α counts <2000 show a larger deviation from the median. This also applies to extremely short measurements of only a few hours for U and Th values obtained for the Nussy standard. Apart from that, other short-time measurements for Nussy do not show such a distinct deviation from the median, but only reveal a slightly larger scatter compared to long-time measurements. With respect to the potassium results, the picture is not so clear. For Volkegem, short-time measurements of <2000 α counts at least show a large scatter and a slightly larger deviation from the median than measurements with longer durations. For Nussy, however, neither the deviation from the median nor the inter-measurement scatter indicates that this group of measurements might be less precise than measurements of longer duration. Unlike for thorium and uranium, even measurements with a duration of only some hours do not differ from the median value.

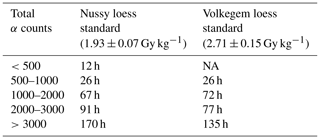

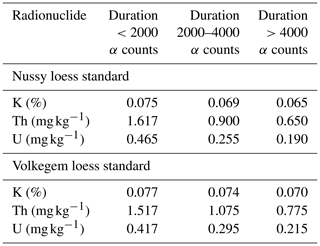

Although there are some sources of uncertainty which do not get smaller with time (see Sect. 2.3), longer-lasting measurements in theory should be expected to be associated with considerably smaller uncertainties due to better counting statistics. In summary, our results confirm this relationship, which might be derived from Fig. 5 and becomes quite obvious when looking at the average measurement uncertainties for different groups of measurements arranged by their respective durations (expressed by their total number of α counts); these are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8Averaged uncertainties for μDose measurements of loess standards Nussy (upper part) and Volkegem (lower part) grouped by their respective total numbers of α counts.

Overall, the measurement uncertainties are reduced by longer measurement times. This applies to both loess standards and to all radionuclides. The biggest reduction, however, is observed when comparing short-time measurements of <2000 α counts to those showing a total number of α counts of 2000–4000 (i.e. medium-time measurements). For the Nussy loess standard for instance, relative reductions of uncertainties of ∼ 8 % (K), ∼ 44 % (Th) and ∼ 45 % (U) are achieved. With 4 % (K), 29 % (Th) and 29 % (U) similar but smaller relative reductions in uncertainties can be determined for the Volkegem loess standard when short-time and medium-time measurements are compared.

A further increase to long measurement durations corresponding to more than 4000 α counts (long-time measurements) further reduces the uncertainties, yet typically not to the same extent as for the medium-time measurements. For the Nussy loess standard, prolonged measurements of >4000 α counts correspond to relative reductions of the original (short-time) uncertainties of 13 % (K), 59 % (Th) and 60 % (U). Particularly for U and Th, these values are only slightly higher than those of the reduction for medium-time measurements. With total relative reductions of 9 % (K), 49 % (Th) and 48 % (U) compared to the short-time measurements, similar results can be found for the Volkegem loess standard.

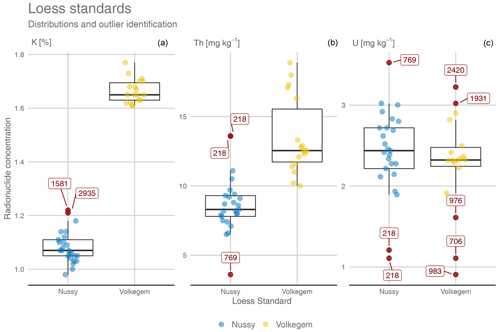

Figure 6Radionuclide concentrations determined by μDose measurements given as percent for K (a) and as milligrams per kilogram (mg kg−1) for Th (b) and U (c). The different colours represent the different loess standards investigated (see legend). Outliers (red circles) were identified based on the 1.5 IQR criterion and are labelled with their respective number of total α counts.

In Fig. 6 the obtained results for radionuclide concentrations are illustrated as box–whisker plots. This allows identifying statistically relevant outliers which were determined based on the 1.5 interquartile range (IQR) criterion, i.e. the difference of the third and the first quartile of the whole data set as shown by the box, extended in both the lower and upper direction by a factor 1.5 IQR as illustrated by the whiskers. Values outside this range are highlighted by red circles and labelled with their respective measurement durations expressed as the total number of α counts. From Fig. 6 it can be concluded that the majority of outliers arise from short-time measurements of <2000 α counts, which equals measurement durations of approximately 1 d or only a few hours. Only three medium-time measurements revealing α counts of ∼ 2400, ∼ 2900 and ∼ 3500 have been identified as outliers. Therefore, we conclude that the probability of obtaining results not consistent with the average values is higher for short-time measurements showing a total number of α counts of less than 2000.

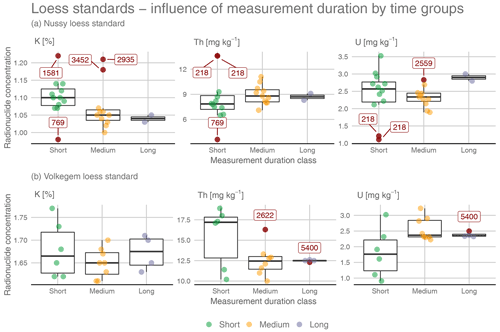

Figure 7Radionuclide concentrations determined by μDose measurements given as percent for K (left) and as milligrams per kilogram (mg kg−1) for Th (centre) and U (right). Results of individual measurements and box plots for the loess standards Nussy (a) and Volkegem (b). Data grouped by measurement duration into three classes: short-time (<2000 α counts; green symbols); medium-time (2000–4000 α counts; yellow symbols); long-time (>4000 α counts; grey symbols). Outliers (red symbols) as identified by the 1.5 IQR criterion and labelled with their respective numbers of total α counts. Classification is not based on specific statistical arguments but reflects the realization of the experiments.

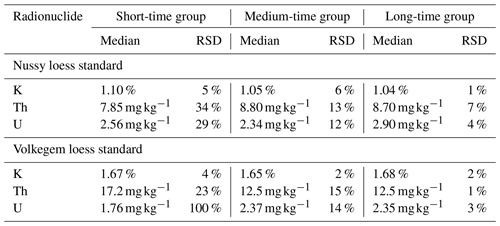

Table 9Median values and relative standard deviations (RSDs) for radionuclide concentrations of the loess standards Nussy (upper part) and Volkegem (lower part) derived from μDose measurements. The individual measurements were classified into three groups of measurement durations based on the total number of α counts (short-time group: <2000 α counts; medium-time group: 2000–4000 α counts; long-time group: >4000 α counts).

For Fig. 7 the data were grouped according to measurement durations, which illustrates the impact of measurement time even more evidently and supports the conclusions drawn from Figs. 5 and 6. With respect to the uranium and thorium contents of the Volkegem loess standard (Fig. 7 lower part), medium- and long-time measurements agree rather well. For uranium, the median values are 2.35 mg kg−1 (long) and 2.37 mg kg−1 (medium) with associated relative standard deviations (RSDs) of 3 % and 14 %, respectively. For thorium, median values of 12.5 mg kg−1 (RSD = 9 %; long) and 12.5 mg kg−1 (RSD = 15 %, medium) were derived. These group medians are identical within errors and reveal rather small intra-group scatter (at least when compared to the short-time group). For the short-time measurements, the results are completely different. Here, median values of 1.76 mg kg−1 (RSD = 43 %) for uranium and 17.2 mg kg−1 (RSD = 24 %) for thorium were calculated. These median values clearly differ from those determined for either the long-time or the medium-time group. For uranium, the short-time measurements underestimate the medium- and long-time measurements by ∼ 25 %. For thorium, an overestimation of ∼ 38 % can be observed. With respect to the results obtained for potassium, the picture is not as clear as for uranium and thorium. The median values (short: 1.67 mg kg−1; medium: 1.65 mg kg−1; long: 1.68 mg kg−1) show rather good agreement. Only the slightly larger scatter in data observed for the short-time measurements (RSD = 4 %) compared to the medium- (RSD = 2 %) and long-time (RSD = 2 %) groups suggests that the short-time measurements might not provide reliable results (see also Table 9).

For the Nussy loess standard (Fig. 7, upper part), the results are more difficult to interpret. The median values indicate differences between the groups of measurement duration. However, the results summarized in Table 9 (upper part) are not as evident as for the Volkegem loess standard. Potassium contents calculated for long-time and medium-time measurements agree very well (long: 1.04 %; medium: 1.05 %), whereas the short-time value of 1.10 % deviates from these two values. However, the relative deviation is only ∼ 6 %. For thorium, we have a similar result. The median values of the medium- and long-time measurements are identical within errors, but do not significantly deviate from the results obtained for the short-time group, which slightly underestimates (∼ 10 %) the results calculated for the other two groups. For uranium, the long-time measurements slightly overestimate (∼ 13 %), while short-time and medium-time groups show rather good agreement. With respect to the median values, the results suggest that the short-time measurements might be problematic. However, the evidence is not as clear as for the Volkegem loess standard. Showing values of 29 % and 34 % for uranium and thorium, respectively, at least the RSDs are rather large for the short-time measurements. Here, medium- and long-time groups show distinct lower RSDs of 12 % and 13 % (medium) as well as 4 % and 7 % (long). However, this does not apply to potassium for which an RSD of only 5 % could be determined for the short-time measurements. With respect to the outliers identified based on the 1.5 IQR criterion, the majority belongs to short-time measurements of <2000 α counts.

Finally, there seems not to be a straightforward answer to the question of whether there is a particular lower limit of measurement durations for which reliable results can still be expected. Our findings suggest that short-time measurements hold the greatest risk of providing results not in agreement with results obtained by longer-lasting measurements. This might be interpreted as an indicator of an unreliable measurement setup. At least, this is true for very short measurement durations of less than 1 d, which should therefore be avoided. However, since our findings are somehow contradictory and might even point to a more or less sample-specific pattern, this conclusion should be regarded as a conservative rule of thumb.

In summary, we conclude that reliable results for the loess standards investigated in this study could be obtained by μDose measurements revealing total numbers of α counts of 2000 to 4000. For our samples this number of α counts corresponds to measurement durations of approximately 2–4 d (also see Table D1 in Appendix D). Extremely short measurement durations delivering α counts <2000 should be avoided due to insufficient counting statistics. Despite the benefit of further reducing measurement uncertainties, prolonged measurements of more than 5 d (i.e. >4000 α counts) are normally not necessary to ensure results of reasonable accuracy and precision. Since the counting statistic strongly depends on the sample-specific activity, we advise using the total number of α counts as an indicator for an adequate measurement duration. In our experiments, samples (Nussy and Volkegem) measured for approximately 2–4 d revealed a mean number of ∼ 2400 α counts. Therefore, we suggest a threshold value of ∼ 2500 α counts as a minimum value in order to guarantee reliable measurement results.

5.3 μDose system performance for environmental samples

So far, the performance of the μDose system has only been tested on one synthetic sample with known activity composed as a mixture of different IAEA standards and on a very limited number of natural loess and archaeological samples (see Tudyka et al., 2018, 2020). In order to assess the performance of the μDose system for natural samples on a broader data basis, we carried out a series of inter-laboratory comparisons including TSAC, ICP-OES and low-level HRGS measurements. As our primary aim was to assess the potential of the μDose system to produce reliable data for calculating dose rates of samples with low radionuclide contents typical of natural environments, a total of 47 samples from various environmental settings were re-measured on the μDose devices at the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory.

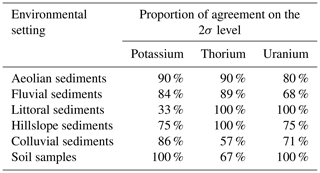

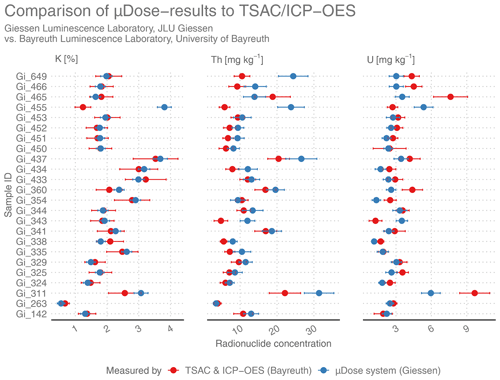

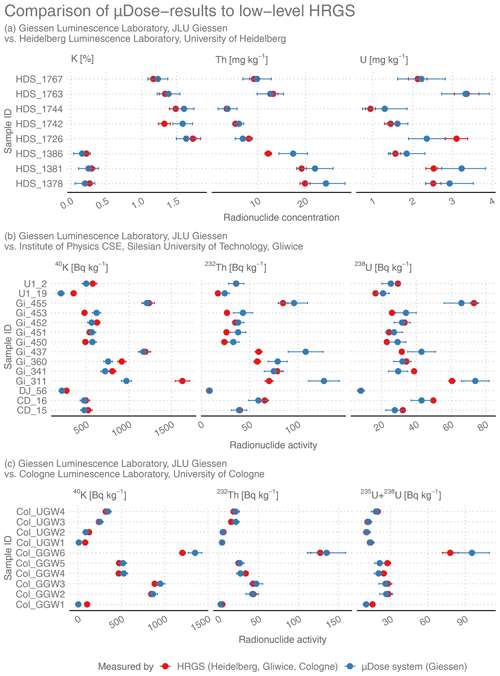

Figure 8Comparison of results obtained by TSAC (U and Th) in combination with ICP-OES (K) (red symbols) to the findings derived from μDose measurements (blue symbols). Please note that the values are given as radionuclide concentrations (% for K; mg kg−1 for U and Th).

Figure 8 shows the results for samples that were measured at the University of Bayreuth by applying TSAC for the determination of uranium and thorium contents and ICP-OES for potassium. For most samples, the findings indicate very good agreement between the values derived from μDose measurements (blue symbols) and those obtained by TSAC and ICP-OES (red symbols). For uranium and thorium contents, the majority of samples agree within the 2σ level (U: 63 %, Th: 79 %). The calculated potassium contents often show a perfect match; 95 % of the investigated samples are within the 2σ level of agreement, and 83 % are even within the limits of 1σ.

However, there are also some samples for which the determined values – particularly the determined contents of uranium and thorium – do not coincide on the 2σ level. Among these problematic samples are Gi311, Gi343, Gi360, Gi455, Gi465, Gi466 and Gi649. With respect to the last four of these samples, this pronounced difference of TSAC and μDose values might be attributed to the possible presence of radioactive disequilibria caused by chemical and/or physical differentiation processes potentially affecting long-living members in the U and Th decay chains such as 234U, 230Th, 226Ra, 228Th and 228Ra (e.g. Degering and Degering, 2020; Krbetschek et al., 1994). This explanation is based on the specific context of the respective sampling locations. All four samples originate from Holocene fluvial floodplain sediments covering Pleistocene gravel beds. For such sediments, strongly alternating groundwater levels are characteristic. Generally, sediments exposed to fluctuating groundwater levels are regarded as typical candidates for radioactive imbalances (e.g. Degering and Degering, 2020; Olley et al., 1996, 1997) since they are subject to various translocation processes and potentially significant periodic changes in fundamental environmental conditions such as the pH value. With respect to the differing chemical properties of the individual elements in the decay chains, such imbalances can take several and complex forms, which may manifest either in a loss or in an accumulation of specific parent and daughter nuclides (e.g. Prescott and Hutton, 1995). Therefore, it appears not unlikely that the samples mentioned above suffer from distinct increases and/or decreases in particular radioactive daughter nuclides in the U and Th decay chains. Regardless of the specific nature of these potential imbalances, their existence would violate a central assumption of the specific algorithms used by the μDose system, which would most probably cause inadequate results for the calculated activities.

For the other samples, a lack of secular equilibrium might also be a suitable explanation for the detected deviations of measurement values. This might at least be true for samples Gi311 and Gi343. Both are colluvial samples which were taken from locations within profiles that were identified in the field as M-Go horizons according to the German soil classification system (Ad-Hoc-AG Boden, 2005). These horizons showed typical features of a gleysol, revealing inter alia a characteristic accumulation of sesquioxides, which indicate a periodical impact of groundwater. As a result, secular disequilibria appear to be possible for these samples.

Figure 9Comparison of results obtained by HRGS in different laboratories (red symbols) to the findings derived from μDose measurements (blue symbols). (a) Samples provided by the Heidelberg Luminescence Laboratory. Please note that these values are given as concentrations (% for K; mg kg−1 for U and Th). For Gliwice and Cologne laboratories values are given as activities (Bq kg−1). Only the 238U-specific activity is shown for the samples measured in the Gliwice laboratory (b), while the combined activity of 235U and 238U is depicted for the samples from Cologne (c).

Figure 9 illustrates the results for the comparison of μDose measurements (blue symbols) with low-level HRGS (red symbols) performed in different laboratories. Figure 9a shows the results for the samples from the Heidelberg Luminescence Laboratory. On average, the obtained values are characterized by rather small discrepancies between μDose results and HRGS. The majority of Heidelberg samples agrees with the μDose results within either the 2σ level (U: 88 %; Th: 88 %; K: 88 %) or even within the 1σ level (U: 50 %; Th: 50 %; K: 75 %).

Figure 9b shows various samples that were measured at the Gliwice laboratory. Apart from samples provided by the Gliwice laboratory itself, these measurements also included some samples provided by the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, which had previously been measured at the University of Bayreuth by applying TSAC and ICP-OES. With respect to these latter samples, the results obtained in Gliwice largely confirm the findings already discussed for the comparison of μDose measurements to TSAC and ICP-OES. For samples Gi311, Gi453 and Gi360, there is again a pronounced deviation of the μDose results from the independently obtained data. Sample Gi437, which was just within the limit of 2σ deviation for the TSAC comparison, did not conform on the 2σ level when compared to the results from Gliwice. Particularly, this applies to the activities arising from 232Th and 238U. However, with respect to sample Gi455, the situation is different. While this sample showed the largest differences for the comparison to TSAC and ICP-OES, the values obtained by HRGS reveal 2σ agreement with the μDose results. A straightforward interpretation of this finding is hardly possible, but it casts doubt on the explanation suggested above that Gi455 might suffer from a distinct radioactive disequilibrium. In fact, the extraordinary large discrepancies observed for Gi455 in the TSAC/ICP-OES comparison and the good agreement of μDose results and low-level HRGS values might rather indicate a serious problem during the TSAC/ICP-OES measurements. The amount of discrepancy observed for Gi455 particularly supports this interpretation since other samples originating from the same sampling location (Gi450–Gi453) do not show similar discrepancies. Furthermore, Gi455 was identified as a sample originating from floodplain loams of the Lahn river (see detailed description of sample materials in Appendix C). Based on long-lasting experience with sediments from the Lahn catchment in the Giessen Luminescence Laboratory, floodplain material from the Lahn catchment is expected to show significantly higher concentrations of thorium and uranium than material originating from fluvial gravels of the region. However, the TSAC/ICP-OES results obtained for Gi455 are of the same order of magnitude as the results obtained for Gi450–Gi453, which originate from the underlying terrace gravels. In the end we cannot be sure whether the distinct deviations observed for Gi455 were caused by problems during the TSAC/ICP-OES measurements or whether they can be explained by the presence of a radioactive disequilibrium.

Overall, the 2σ-level proportions of agreement for all samples measured in Gliwice (including those from Giessen) are 64 % (U), 50 % (Th) and 64 % (K). At first glance, this could be misinterpreted as an indication of serious methodological shortcomings. However, it has to be kept in mind that these measurements included a large number of samples from the Giessen laboratory which were previously identified as potentially problematic. Although the HRGS measurements in Gliwice did not give clear evidence of radioactive disequilibria, the presence of such disequilibria seems to be likely for at least 8 out of 14 measured samples when the specific sampling locations are considered.

Restricting the analysis to the five samples provided by the Institute of Physics in Gliwice for which no radioactive disequilibria were expected, the results are completely different. Except for sample U1_19, all samples reveal very good or even excellent agreement with the μDose results from Giessen. On the 2σ level, the proportions of agreement between HRGS and μDose are 80 % for K and Th and 100 % for U. So far, we have not been able to find any reasonable explanation for the pronounced deviation of K and Th activities determined for sample U1_19.

With respect to the samples from the Cologne Luminescence Laboratory, the findings are also very good. Except for the potassium contents of three samples (COL_GGW1, COL_GGW6 and COL_UGW1) for which a distinct difference in the respective values is obvious, all values show excellent agreement with the μDose results. But also 50 % of the results for 40K conform on the 2σ level. For the activity of 235+238U, 90 % of the determined values agree on the 2σ level and 60 % still coincide within 1σ. For 232Th, activities determined by μDose and HRGS show a nearly perfect match: 100 % of the values agree within 2σ and 70 % still within 1σ.

Surprisingly, this is also true for four samples for which radioactive disequilibria had been identified (COL_UGW1 to COL_UGW4). With respect to 235+238U and 232Th activities, a 100 % proportion of agreement on the 1σ level can be derived from the data and for 40K still 50 %. In theory, the algorithm applied by the μDose software should not yield correct results since a major assumption of this algorithm is violated in the presence of radioactive disequilibria. As a consequence, we should expect large discrepancies between the applied methods since the determination of radionuclide activities in low-level HRGS and in the μDose system is based on differing approaches. Yet, our findings suggest that radioactive disequilibria are not necessarily associated with such large inter-methodological discrepancies. Although such discrepancies were detected for some of the analysed natural samples, this obviously did not apply to samples COL_UGW1 to COL_UGW4. A convincing explanation for this inconsistency can hardly be found at this moment. The findings for the Cologne samples are only based on a limited number of samples and are not supported by results obtained from the comparisons to the other laboratories (Bayreuth and Gliwice). In the end, the possibility cannot be excluded that the results obtained for the four Cologne samples only match by chance. At the moment, we cannot decide whether these results are only odd anomalies or whether they represent the normal case for samples in radioactive disequilibria. In order to give a final answer, further detailed and systematic investigations are required, including the question of whether the magnitude of radioactive disequilibria is a decisive factor for the μDose system's capability to determine values for the radionuclide concentrations that are in good agreement with results obtained by other methodological approaches. Regardless of the final answer to this question, we would like to point out that dose rates calculated from radionuclide concentrations of samples for which radioactive disequilibria have to be assumed will never be an accurate measure for trapped charge dating and should therefore be treated with care.

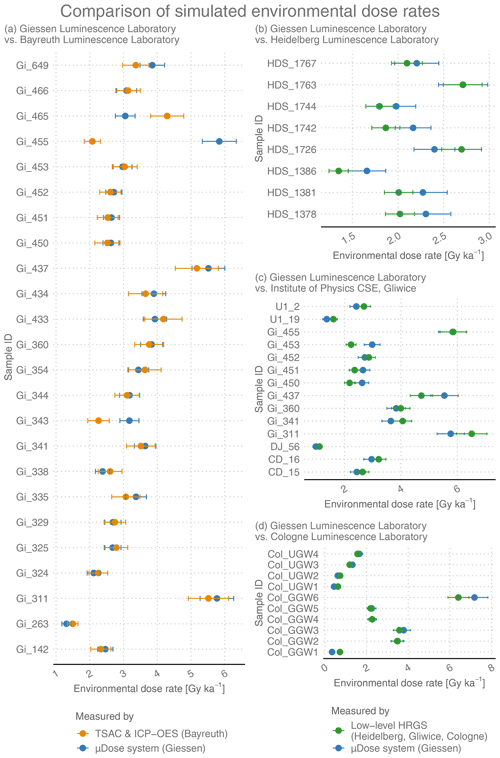

Figure 10Comparison of simulated environmental dose rates for various natural samples. Assuming a constant water content of 15±5 % and a constant cosmic radiation of 0.150±0.015 Gy ka−1, all values were calculated for the 90–200 µm grain size fraction of HF-etched quartz using DRAC v1.2 (Durcan et al., 2015). Please be aware that these calculated values do not correspond to the actual dose rates and are thus referred to as “simulated environmental dose rates”. For details the reader is referred to the table notes of Table 4.

The overall good performance of μDose measurements is confirmed by the rate of agreement observed for the simulated environmental dose rates illustrated in Fig. 10. As described for the Nussy and Volkegem loess standards (see Sect. 5.1), these dose rates were calculated for the coarse (90–200 µm) grain fraction of HF-etched quartz using DRAC v1.2 (Durcan et al., 2015). For calculation, we applied the conversion factors provided by Guérin et al. (2011) and used a constant water content of 15±5 % as well as constant cosmic radiation of 0.150±0.015 Gy ka−1. We would like to point out that these values were arbitrarily chosen and do not represent the actual moisture and cosmic radiation values that might be detected for the different sampling locations.

Figure 10a shows a comparison of μDose-based simulated environmental dose rates to values derived from TSAC/ICP-OES measurements performed at the Bayreuth Luminescence Laboratory. With samples Gi343, Gi455 and Gi465, there are three samples for which agreement could not be achieved on the 1σ level or on the 2σ level. These samples have already been identified to be problematic (see discussion above). With respect to the Bayreuth samples, 88 % of the simulated environmental dose rates coincide within 2σ and 79 % still within 1σ.

Figure 10b–d illustrate the results of μDose–HRGS comparisons for different laboratories. With 25 % (Heidelberg), 36 % (Gliwice) and 50 % (Cologne), the proportions of samples for which agreement on the 1σ level can be observed is substantially lower than for the μDose–TSAC/ICP-OES comparison. On the 2σ level of agreement, 100 % (Heidelberg), 86 % (Gliwice) and 80 % (Cologne) of the calculated simulated dose rates coincide with the respective dose rate values derived from μDose measurements.

Overall, 55 % of the simulated environmental dose rates for all investigated samples coincide within 1σ and 88 % show agreement on the 2σ level. In total, the measured-to-given ratios range from 0.48 to 2.81 and average at a value of 1.04, which improves to 1.00 if the above-mentioned three problematic samples are not considered. 80 % of the calculated measured-to-given ratios lie within 15 % of unity, indicating an overall very good rate of agreement for the simulated environmental dose rates. In summary, we can conclude that μDose measurements provide results which allow the calculation of dose rates that are in accordance with dose rate values derived from well-established methods of environmental dose rate determination.