the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Technical note: Investigation into the relationship between zircon structural damage and Pb mobility using chemical abrasion, SIMS, Raman spectroscopy, and atom probe tomography

Charles W. Magee Jr.

Lutz Nasdala

Renelle Dubosq

Baptiste Gault

Simon Bodorkos

Chemical abrasion (CA), a two-step process of annealing and partial dissolution, is routinely applied to zircon grains prior to U–Pb geochronology to dissolve portions of the grains affected by Pb loss prior to analysis. Despite the utility of the technique, it is not clear what the more HF-soluble material produced in the annealing step is, what degree of lattice damage causes it to form instead of zircon, how to predict if a specific sub-volume of a zircon will survive CA, or how any of these processes relate to Pb mobility. In this study, we use secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), Raman spectroscopy, and atom probe tomography (APT) to constrain what happens to both concordant and discordant zircon during each step of the CA process. We find that zircon in SIMS sputter craters which have undergone Pb loss generally have more heterogeneous Raman band widths than in those sputter craters where Pb has been retained. Annealing drastically reduces Raman band widths, but some heterogeneity is still present in discordant sputter craters. APT results from all samples which successfully ran were homogeneous in U, Pb, Th, and most other elements in all cases. This makes it hard to link Pb loss and lattice damage at the submicrometre scale by direct imaging in this study. However, as the zircon sputter craters with Pb loss show homogeneous APT results, we recommend against using homogeneous APT results as an indicator of closed-system U–Pb behaviour.

- Article

(4642 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(24910 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Chemical abrasion (CA) is a method used to improve the accuracy and precision of U–Pb dating in zircon by the preferential dissolution of parts of the zircon which have undergone Pb loss. The assumption is that domains of the zircon which have experienced Pb mobility will not anneal back into zircon but will instead become some other phase which is preferentially dissolved by HF at lower temperatures. The exact nature of the soluble phase formed by annealing is not known, although McKanna et al. (2023) show that it is heterogeneous down to the submicrometre limit of their analyses, and Kooymans et al. (2024) show that chemically abraded OG1 zircon has a lower hydroxyl content than untreated OG1 zircon.

McLaren et al. (1994) show that annealing fully metamict zircon at a time and temperature similar to the CA annealing step causes metamict zircon to form discrete ZrO2 and SiO2 phases, which are intergrown on the scale of tens of nanometres. Thus, if the material preferentially dissolved in CA undergoes this same decomposition reaction as metamict zircon, it should be visible using a nanoscale imaging technique.

An atom probe is a mass spectrometer with subnanometre spatial resolution, in principle with a similar sensitivity to all elements in the range of tens of ppm (Gault et al., 2010, 2021). Atom probe tomography (APT) is the tomographic reconstruction of the analysed volume based on the temporal and spatial arrival of ions at the detector. This combination of high spatial and chemical resolutions makes it attractive to study property-modifying nanoscale microstructural features. A number of nanofeatures related to various types of alteration have previously been documented in zircon (Valley et al., 2014; Piazolo et al., 2016; Peterman et al., 2016, 2021). Conversely, reference zircons generally produce homogeneous results (Exertier et al., 2018; Saxey et al., 2018). This has led some researchers to use a homogeneous APT result in zircon as an indicator for closed U–Pb system behaviour (Greer et al., 2023).

Although APT cannot directly image voids, Dubosq et al. (2020) use the electric field distortion caused by voids, and the tomographic reconstruction artefacts generated by this distortion, to detect nanometre-scale fluid inclusions. If the CA dissolution voids observed by McKanna et al. (2023) extend to the nanoscale, this should also be visible in APT.

A review about the intersection of radiation dosage, aqueous alteration, lattice damage, and Pb mobility is beyond the scope of this paper. In short, it is not known what combination of radiation damage, aqueous alteration, and other factors induce the crystallographic change to zircon which allows Pb mobility. Although zircon domains which have lost radiogenic Pb also often gain common Pb and light rare earth elements, the extremely low abundance of 204Pb and lanthanum means that they cannot be used as diagnostic at the submicrometre scale, as a nanometre-scale volume is expected to contain less than one atom of ppb-level components. The goal of this project was to see if APT could, in addition to imaging predicted features in annealed and chemically abraded zircon, also find a diagnostic difference in between untreated closed- and open-system zircon.

2.1 OG1 target zircon

The OG1 zircon (Stern et al., 2009) was selected for this study due to its well-characterised nature and extensive use as a reference zircon (Stern et al., 2009; Magee et al., 2017; Kemp et al., 2017; Petersson et al., 2019). Measurements of untreated zircons by both TIMS and secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) identify slight Pb loss, which is ameliorated by chemical abrasion (Stern et al., 2009; Kooymans et al., 2024). This study used archived chemically abraded OG1 (in mount GA5015) and annealed but not partially dissolved material (in mount GA5005). Following crystallisation at 3465 Ma, the Owens Gully Diorite underwent regional amphibolite-grade metamorphism around 3.3 Ga (François et al., 2014), and the U–Th–He age of the zircons is about 750 Ma (Magee et al., 2017), indicating that it has been cool enough to accumulate radiation damage since at least that time.

2.2 Specimen treatment and selection

OG1 zircon grains were annealed in a quartz boat for 48 h at 1000 °C (Bodorkos et al., 2009). The chemically abraded grains were subsequently partially dissolved in HF at 200 °C for 10 h at the Royal Ontario Museum, and the annealed grains had no further treatment. Aliquots of several hundred grains were then mounted in two 25 mm epoxy discs and polished. Both mounts contain the TEMORA-2 reference zircon (Black et al., 2004). Transmitted light, reflected light, and cathodoluminescence images of all zircons were taken prior to SIMS analysis. After the experiments described by Bodorkos et al. (2009), these two mounts were stored in the Geoscience Australia archive before being retrieved for this study.

2.3 SIMS U–Pb analysis

Mounts GA5005 and GA5015 were run side by side in a single combined SIMS U–Pb session on the Geoscience Australia sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe (SHRIMP) IIe. A primary beam of O with approximately 10.68 kV impact energy and a primary beam monitor (PBM; net sample current) current of approximately −2 nA was projected through a 100 µm aperture to sputter a flat-bottomed ellipsoidal crater approximately 16×21 µm across and 1 µm deep. Analytical techniques were otherwise as per Magee et al. (2012).

2.4 Raman spectroscopy

The degree of accumulated radiation damage in zircon was estimated from the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the ca. 1000 cm−1 Raman band (Nasdala et al., 1995), which is assigned to antisymmetric stretching vibrations of SiO4 tetrahedrons (Dawson et al., 1971). Analyses were done by means of a dispersive Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution spectrometer equipped with an Olympus BX-series optical microscope, a diffraction grating with 1800 grooves per mm, and a Peltier-cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) detector. Spectra were excited with the 632.8 nm emission of an He–Ne laser (10 mW at the sample surface), using an Olympus 100× objective (numerical aperture 0.90). Wavenumber calibration was done using the Rayleigh line. The system was operated in full confocal mode, resulting in a lateral resolution of better than 1 µm (compare Kim et al., 2020) and a depth resolution of ca. 2 µm. Hyperspectral maps were obtained using a software-controlled x–y stage in “oversampling” mode (step size in the range 0.6–0.9 µm). Fitted FWHM values were corrected for the artefact of experimental band broadening according to the procedure of Váczi (2014), based on the spectrometer's FWHM of the instrumental profile function (IPF) of 0.8 cm−1 in the red range. For further details, see Zeug et al. (2018).

2.5 Atom probe tomography

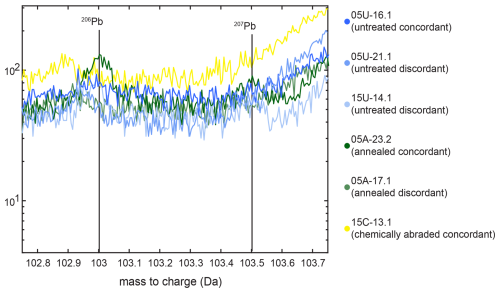

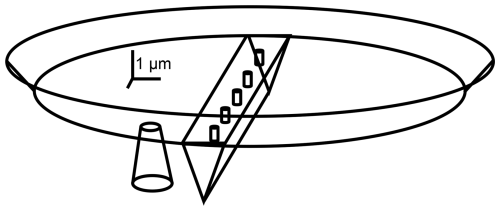

A suite of six zircon samples was selected for APT analysis, i.e., 05U-16.1 (untreated concordant), 05U-21.1 (untreated discordant), 15U-14.1 (untreated discordant), A-23.2 (annealed concordant), A-17.1 (annealed discordant), and C-13.1 (chemically abraded concordant). A series of specimens (n=4–5) was prepared from each sample by in situ liftout (Thompson et al., 2007). The surface was protected by ion beam deposition of an ∼0.5 µm Pt layer, and specimens were shaped into needles with annular milling at 30 kV on a dual-beam scanning electron microscope/focused ion beam (FEI Helios Nanolab 600i or Helios Plasma-FIB) and subsequently cleaned using the ion beam at 5 kV to remove regions potentially severely damaged by the implantation of energetic Ga or Xe ions. The specimens were then analysed by APT in a CAMECA local electrode atom probe (LEAP) 5000 XR fitted with a reflectron lens with a detection efficiency of ∼52 % at the Max-Planck-Institut für Nachhaltige Materialien, Düsseldorf, Germany (Table S1 in the Supplement). The specimens were analysed at a base temperature of 50–60 K, with a laser pulse energy of 400–700 pJ focused on an area estimated to be <3 µm in diameter, a detection rate of 0.03–0.1 ions detected for 100 pulses, and a laser pulse repetition rate of 100–200 kHz. The data processing and reconstruction were done with the commercial software packages AP Suite 6.1 and 6.3. The ranged mass spectrum used for the specimens is shown in Fig. S1 in the Supplement. A schematic showing the relative analytical volumes of SHRIMP, Raman, and APT is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1A scaled drawing showing the relative analytical volume of the SHRIMP, Raman, and APT analytical techniques. Raman and APT volumes are shown in the bottom of a SHRIMP sputter crater, as per this study. SHRIMP sputter crater is approximately µm. Raman excitation volume is approximately 2 µm deep and 1 µm across. The APT ion-milled area removed is about µm, while the individual samples produced are about 0.5 µm × 0.1 µm × 0.1 µm. The SHRIMP and APT are destructive, while the Raman is not.

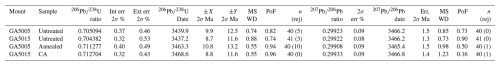

Table 1Population-weighted mean geochronology results for OG1 analyses.

MSWD: mean squared weighted deviation (χ2/υ); PoF: probability of fit. Uncertainties are x/y as per Schoene et al. (2006).

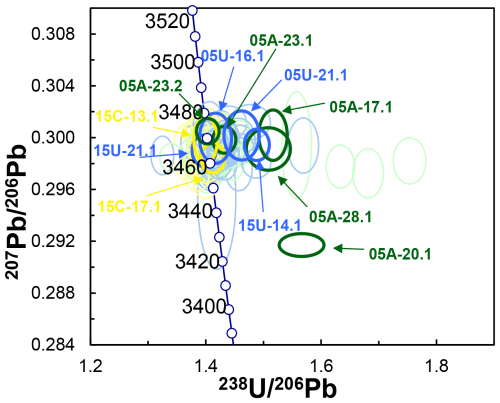

3.1 SHRIMP U–Pb results

SHRIMP results are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. They generally agree with similar recent studies from this lab (Magee et al., 2023; Kooymans et al., 2024). A total of 11 individual SIMS sputter craters (2 untreated concordant, 2 untreated discordant, 2 annealed concordant, 3 annealed discordant, and 2 CA concordant) were chosen for further study using hyperspectral Raman imaging. The U–Pb systematics of these spots are shown in Table 2.

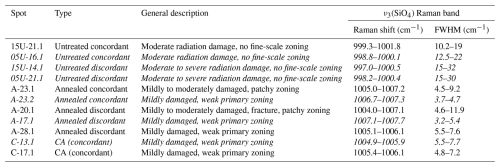

Table 2Geochronology results for spots subject to Raman mapping.

Note: samples in italics were selected for APT analysis after Raman mapping. Bd: below detection.

a f 206: common 206Pb total 206Pb, calculated from the observed 204Pb.

b U–Pb discordance: difference between the 204Pb-corrected and ages.

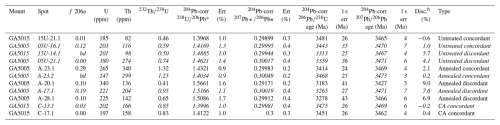

3.2 Raman spectroscopy and mapping

The FWHM of the main zircon Raman band near 1000 cm−1 is 1.7–1.8 cm−1 for well-ordered zircon (Nasdala et al., 2002; Zeug et al., 2018) and increases to well above 30 cm−1 at elevated stages of damage accumulation (Nasdala et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2000). In the present study, FWHM values between 3.2 and 32 cm−1 were obtained (Table 3), characterising the samples as spanning almost the entire range from mildly to severely radiation-damaged. Untreated grains of OG1 are in general moderately to severely radiation-damaged (FWHMs in the range 10–32 cm−1), with significant zoning and/or patchy heterogeneity on a scale of within single SHRIMP spots. This is new information, as the OG1 reference zircon has, to the best of our knowledge, never been subjected to any systematic quantitative study of the structural state and its internal heterogeneity, even though cathodoluminescence (CL) images obtained from polished grains indicated some degree of internal structural zonation (Stern et al., 2009; for the dependence of luminescence intensity on radiation damage, see Nasdala et al., 2002; Lenz and Nasdala, 2015).

Band widths for the annealed and chemically abraded grains (FWHMs 3–12 cm−1) were in general much narrower than those of the untreated grains. Based on results of recent annealing studies (Ginster et al., 2019; Ende et al., 2021), the above FWHM values (obtained after samples had experienced 48 h at 1000 °C) indicate initial FWHMs of 6–30 cm−1 before annealing. There are no systematic differences between structural states of annealed-only and annealed plus chemically abraded samples, nor are there systematic differences in degrees of radiation damage between concordant and discordant spots, even though the latter seem to be slightly more heterogeneous. Most of the discordant grains yielded heterogeneous FWHM distribution patterns across the SHRIMP analysis pits (Fig. 3). There are generally zones or linear features in the sputter crater maps, showing areas of narrower and wider bands.

Figure 3Pairs of Raman maps (step sizes in the range 0.6–0.9 µm) obtained from selected SHRIMP analysis pits, showing distribution patterns of fitted parameters of the main ν3(SiO4) zircon band near 1000 cm−1. Left: intensity on an arbitrary greyscale, visualising the locations of spots. Right: FWHM (the locations of SHRIMP pits are visualised by dashed ovals). Colour-coded FWHM ranges (given in cm−1) are 10–28 (05U-21.1; 05U-16.1), 4–12 (05A-20.1), 3–7 (05A-23.2), and 4–9 (15C-13.1), respectively.

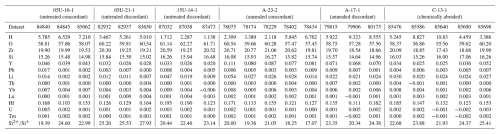

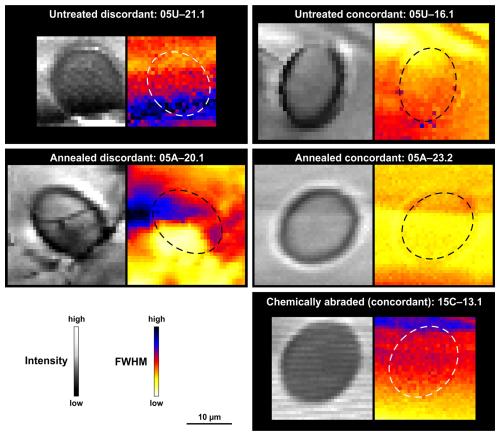

3.3 APT results

A total of 22 specimens from the six zircon samples were successfully analysed with APT. All datasets yield similar compositions for zircon major components (i.e., 17.4 at %–21.1 at % Zr, 14.6 at %–17.1 at % Si, and 57.3 at %–62.3 at % O; Table 4). Other element species detected in APT include H, Hf, Y, Pb, Li, Yb, U, Th, Lu, and Tm (Table 4). To evaluate the measurement reliability, the composition of zircon components (Zr, Si, O, H, Y, Pb, Li, Hf, and U) is plotted against the estimated electric field for each dataset (Fig. S2). The electric field strength during experiments is approximated using the charge-state ratio of as a proxy. The plots indicating the composition versus field estimate for each of the mentioned species show no apparent trends across datasets from the same sample, thus validating the comparison of the composition obtained from the different experiments. Furthermore, there are no significant trends in compositions between treatment types or Pb retention, indicating similar compositions across samples. The only discernible trend is observed for Y, Pb, and Li, where their compositions are slightly higher in annealed samples compared to chemically abraded and untreated samples. Similarly, the compositions of the same species across different regions of interest within a single specimen (sample 05A-23.2, dataset 78075) were plotted against the estimated field for each region to assess the stability of APT experiments during extended runs (>6 h; Fig. S3). Throughout a single analysis, the electric field displays minimal variation, with ratios ranging from 17.35 to 17.81, while compositions remain consistent despite the minimally fluctuating field.

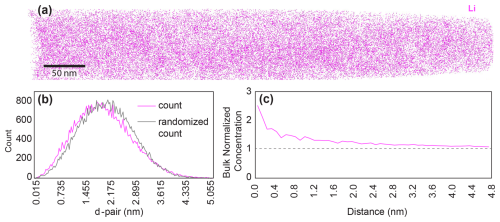

Figure 5Li distribution analysis. Sample 05A-23.2. (a) Li atom locations in tomographic reconstruction. (b) Comparison of observed (pink) and expected (black) d-pair distance. (c) Bulk-normalised concentration of Li versus distance.

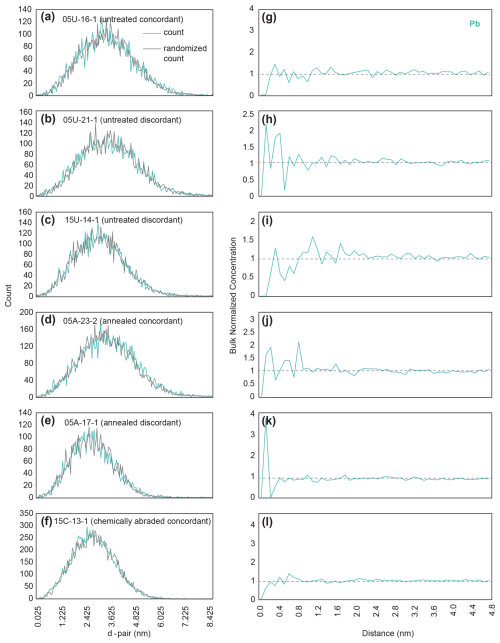

Figure 6Pb distribution analysis. (a–f) Count versus randomly generated count versus nearest-neighbour distance. (g–l) Difference between random and measured counts versus distance.

All datasets had minor 103 and 103.5 Da peaks (206Pb and 207Pb, respectively) above background; however, the 208Pb peak at 104 Da overlaps with 28SiO (Figs. 4, S1, S4). Therefore, only the peaks at 103 and 103.5 Da are considered in the bulk composition analysis and used to evaluate the distribution of Pb in the datasets. The 3D reconstructions of all datasets reveal a homogeneous distribution of Pb and every other major or trace element (Fig. S5), with the exception of Li in sample 05A-23.2 (annealed concordant; Fig. 5a). A nearest-neighbour analysis, which measures the distance between each Pb ion and its closest Pb ion neighbour (d-pair) and plots it against a randomised distribution of ions, confirms the homogeneity of Pb distribution in each sample (Fig. 6a–f). The homogeneous distribution of Pb is also confirmed in each sample by performing a radial distribution analysis whereby the bulk-normalised composition of each species is plotted as a function of its radial distance to the nearest Pb ion (Fig. 6g–l). Since the bulk composition of Pb hovers about a value of 1 for each dataset, homogeneity can be assumed. In sample 05A-23.2 (annealed concordant), the frequency distribution of the d-pair distances for Li is skewed towards lower distances when compared to the randomised distribution curve, suggesting inhomogeneity (Fig. 5b). The radial distribution analysis of Li for sample 05A-23.2 reveals elevated bulk-normalised compositions of Li for short radial distances, also confirming the heterogeneous distribution of Li in the sample (Fig. 5b, c).

4.1 Raman

Using the measurement parameters detailed in Materials and methods yielded excellent results despite topographic features of the sputter crater and thin (estimated 20 nm) crater-bottom zone of primary ion-induced lattice damage from the SIMS primary ion bombardment. Untreated discordant zircon tended to have regions where the FWHM exceeded 30 cm−1, while, in concordant zircon, the maximum FWHM was generally less than 25 cm−1 (Table 3). This reconfirms that radiation damage lowers the Pb retention performance of zircon. As expected, after annealing (without and with additional CA), zircon recovers much of the radiation damage, indicated by significantly narrower Raman FWHMs. Here, degrees of damage of discordant and concordant spots overlap, making clear conclusions impossible. Concordant and discordant spots (in both untreated and annealed/CA grains) differ insofar as discordant samples show somewhat higher extents of structural heterogeneity across the SHRIMP analysis pit (Fig. 3). Overall, Raman spectroscopy alone does not explain why annealed zircon yields concordant or discordant ratios. Raman responses of the chemically abraded samples were similar to the annealed ones in terms of band width and had few features. This technique could potentially be used prior to spatially resolved U–Pb analyses to find the best spots for analysis, although the time and potential expense involved would probably limit such use to very valuable samples.

4.2 Nanoscale element distribution

Elements detected include O, Si, Zr, H, Hf, Y, Pb, Li, Yb, Lu, Tm, U, and Th. Hydrogen is considered to be a contaminant from the vacuum. Nearly all zircon components revealed a homogeneous distribution in all specimens, with the single exception of Li in 05A-23.2. Aluminium was not detected. This is consistent with the near-mantle O isotope values of OG1 (Ávila et al., 2020), which indicate minimal crustal assimilation by the parental magma and the low (<3 ppm) Al concentrations recorded in previous studies of OG1 zircon (Kooymans et al., 2024). In contrast, Y is abundant in OG1 zircons, with Kooymans et al. (2024) reporting median values in excess of 1000 ppm. Nonetheless, there is no evidence of clumping of Y and/or Pb in any of the analysed APT specimens. This suggests that the regional metamorphic grade of amphibolite (François et al., 2014), which gives the Owens Gully Diorite its foliation, was not hot or long enough to initiate the Pb ± Y ± Al clump formation seen in zircons subject to hotter granulite or UHT conditions (Peterman et al., 2016; Piazolo et al., 2016). Phosphorus was not detected; spatial correlation between Y and P was not possible.

Since all elemental distributions are homogeneous across all specimens, no discernible differences can be attributed to the treatment types at the APT scale of tens to hundreds of nm. Similarly, no differences are observed between discordant and concordant grains. SHRIMP analyses with up to 9 % discordance yield APT results that are homogeneous and identical to concordant grains, despite being from areas with the highest levels of lattice damage, as shown by Raman spectroscopy. Potential explanations for the homogeneous distribution of elements are discussed below. Based on these data, we suggest that APT not be used as the sole method for determining closure in the U–Pb system for zircon.

McKanna et al. (2023) show that CA produces voids down to the submicrometre limit of their spatial resolution. Wang et al. (2020) demonstrate that APT can detect voids in metal alloys in the form of artefacts showing apparent clustering or dispersion of matrix ions due to trajectory aberrations during evaporation caused by the distortion of the electrostatic field created by the void. Dubosq et al. (2020) demonstrate that this technique can also be used in geologic materials by identifying voids in the form of fluid inclusions in Archean pyrite. As all elements in the atom probe results from the chemically abraded sample (C-13.1) are homogeneous, we have no evidence that CA produces voids at the nanometre scale of the fluid inclusions by Dubosq et al. (2020).

The homogeneous distribution of Si and Zr in the annealed samples (A-17.1, A-23.2) suggests that the formation of amorphous silica and ZrO2 through annealing metamict zircon at similar temperatures, as demonstrated by McLaren et al. (1994), has not occurred in any of the eight APT tips successfully run from these samples.

4.3 Potential mechanisms of Pb loss

Micrometre- to submicrometre-scale heterogeneity needs to be regarded as one feature potentially favouring secondary loss of radiogenic Pb. Heterogeneous volume expansion of neighbouring sample volumes results in complex strain patterns and, if the elasticity maximum is exceeded, the opening of fractures that then may serve as ideal pathways for fluids (Peterman et al., 1986; Chakoumakos et al., 1987; Lee and Tromp, 1995; Nasdala et al., 2010). However, on the resolution scale of a powerful optical microscope, such fractures were not always observed. Nonetheless, McKanna et al. (2023, 2024) show that chemical abrasion selectively dissolves zircon in such a manner down to the limit of their imaging resolution (about 0.5 µm) and that the leachate solutions from the CA partial dissolution have disturbed U–Pb systematics.

If the discordant areas in zircon are discrete areas of damage distributed within a matrix of isotopically closed zircon, there is a possibility that sampling might miss these regions purely by chance. The likelihood of missing the damaged areas by chance depends on the distribution of Pb loss. If disturbed regions are a mix of intact and damaged areas, the probability of randomly sampling only the intact areas is low, calculated as (1−damaged fraction)n. Considering a SHRIMP spot with 5 % Pb loss, where the Raman can exclude 75 % of the spot area as having lost Pb, the remaining 25 % of the spot would then account for the Pb loss. Given this scenario, the remaining area would have experienced a 20 % Pb loss. The most extreme possibility is that 20 % of this area has lost 100 % of its Pb and that the remaining 80 % is concordant. As this study had nine successful APT analyses (on three discordant grains), the probability of choosing concordant areas by chance is 0.89, or 13 %. It is important to note that this is a maximum, assuming total Pb loss from the altered areas. McKanna et al. (2024) show that the areas altered enough for chemical abrasion to dissolve them still contain significant Pb. If instead we assume that 40 % of the area has suffered 50 % Pb loss, then the probability of sampling only the intact areas drops to 1 % (0.69).

These estimates assume that APT analytical volumes can be chosen and run without bias. It is interesting that, of the eight specimens which failed while being run in the Atom Probe, six were from discordant SHRIMP spots. As the accumulation of radiation damage involves substantial volume increase, heterogeneous self-irradiation of zoned zircon will necessarily result in complex strain patterns (compressive in more damaged and dilative in less damaged volumes). Fracture of APT specimens is generally assumed to be caused by the electrostatic pressure arising from the intense electrostatic field used to field evaporate the surface atoms over the course of the experiment, making brittle materials more prone to early fracture (Wilkes et al., 1972). If strained polyphase material leads to an enhanced propensity for specimen failure before any APT data can be acquired, then there will be a strong selection bias in the results favouring intact zircon. We are not aware of any successful APT analyses of metamict zircon in the literature, either on purpose or by accident. While the inherited cores analysed by Peterman et al. (2016) show Pb loss, that material was reannealed in Mesozoic granulite facies metamorphism and has had minimal radiation damage accumulation since then. It is possible that the APT analytical technique gives a Panglossian view of zircon crystal chemistry, by destroying badly disturbed samples instead of analysing them.

The present study shows that discordant SHRIMP spot analyses were obtained from severely radiation-damaged spots (as indicated by strongly broadened Raman bands). Annealing the zircon samples reduces the band widths in both discordant and concordant zircon, while discordant spots have more residual heterogeneity in their Raman maps. Nevertheless, APT analyses of concordant, discordant, untreated, annealed, and chemically abraded OG1 all show homogeneous distribution of all detected major and minor elements, including U and Pb. As a result, APT cannot identify any differences between concordant SHRIMP spots and those which are up to 7 % discordant. We therefore recommend that APT not be used as a method for determining closure in the U–Pb system for zircon. The similarity between APT results from untreated, annealed, and chemically abraded zircon is difficult to interpret, but it does show that the Pb and Y cluster formation found in high-temperature metamorphism and experimental tests does not appear at the temperatures and times used for chemical abrasion.

Data from all three analytical experiments, and sample maps with spot locations, can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17430613 (Magee, 2025).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-7-591-2025-supplement.

CWM Jr. and SB designed and initiated the experiment. CWM Jr. performed the SIMS analysis. LN performed the Raman analysis. RD and BG performed the Atom Probe analysis. All authors contributed to the text, figures, and tables.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Geoff Fraser and Antony Burnham for internal Geoscience Australia peer reviews. This paper is published with the permission of the CEO of Geoscience Australia.

This paper was edited by Ryan Ickert and reviewed by Donald Davis and Luke Daly.

Ávila, J. N., Holden, P., Ireland, T. R., Lanc, P., Schram, N., Latimore, A., Foster, J. J., Williams, I. S., Loiselle, L., and Fu, B.: High-precision oxygen isotope measurements of zircon reference materials with the SHRIMP-SI, Geostand. Geoanal. Res., 44, 85–102, https://doi.org/10.1111/ggr.12298, 2020.

Black, L., Kamo, S. L., Allen, C. M., Davis, D. W., Aleinikoff, J. N., Valley, J. W., Mundil, R., Campbell, I. H., Korsch, R. J., Williams, I. S., and Foudoulis, C.: Improved microprobe geochronology by the monitoring of a trace element-related matrix effect; SHRIMP, ID-TIMS, ELA-ICP-MS and oxygen isotope documentation for a series of zircon standards, Chem. Geol., 205, 115–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.01.003 , 2004.

Bodorkos, S., Stern, R. A., Kamo, S. L., Corfu, F., and Hickman, A. H.: OG1: A natural reference material for quantifying SIMS instrumental mass fractionation (IMF) of Pb isotopes during zircon dating, Eos Trans. AGU, 90, Fall Meet. Suppl., Abstract V33B-2044, 2009.

Chakoumakos, B. C., Murakami, T., Lumpkin, G. R., and Ewing, R. C.: Alpha-decay-induced fracturing in zircon: The transition from the crystalline to the metamict state, Science, 236, 1556–1559, 1987.

Dawson, P., Hargreave, M. M., and Wilkinson, G. F.: The vibrational spectrum of zircon (ZrSiO4), J. Phys. C, 4, 240–256, 1971.

Dubosq, R., Gault, B., Hatzoglou, C., Schweinar, K., Vurpillot, F., Rogowitz, A., Rantitsch, G., and Schneider, D. A.: Analysis of nanoscale fluid inclusions in geomaterials by atom probe tomography: Experiments and numerical simulations, Ultramicroscopy, 218, 113092, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultramic.2020.113092, 2020.

Ende, M., Chanmuang N., C., Reiners, P. W., Zamyatin, D. A., Gain, S. M., Wirth, R., and Nasdala, L.: Dry annealing of radiation-damaged zircon: Single-crystal X-ray and Raman spectroscopy study, Lithos, 406–407, 106523, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106523, 2021.

Exertier, F., La Fontaine, A., Corcoran, C., Piazolo, S., Belousova, E., Peng, Z., Gault, B., Saxey, D. W., Fougerouse, D., Reddy, S. M., and Pedrazzini, S.: Atom probe tomography analysis of the reference zircon gj-1: An interlaboratory study, Chem. Geol., 495, 27–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2018.07.031, 2018.

François, C., Philippot, P., Rey, D., and Rubatto, D.: Burial and exhumation during Archean sagduction in the East Pilbara Granite-Greenstone Terrane, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 396, 235–251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.04.025, 2014.

Gault, B., Moody, M. P., De Geuser, F., La Fontaine, A., Stephenson, L. T., Haley, D., and Ringer, S. P.: Spatial resolution in atom probe tomography, Microsc. Microanal., 16, 99–110, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1431927609991267, 2010.

Gault, B., Chiaramonti, A., Cojocaru-Mirédin, O., Stender, P., Dubosq, R., Freysoldt, C., Kumar Makineni, S., Li, T., Moody, M. P., and Cairney, J. M.: Atom probe tomography, Nat. Rev. Methods Primers, 1, 51, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-021-00047-w, 2021.

Ginster, U., Reiners, P. W., Nasdala, L., and Chanmuang, N. C.: Annealing kinetics of radiation damage in zircon, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 249, 225–246, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2019.01.033, 2019.

Greer, J., Zhang, B., Isheim, D., Seidman, D. N., Bouvier, A., and Heck, P. R.: 4.46 Ga zircons anchor chronology of lunar magma ocean, Geochem. Perspect. Lett., 27, 49–53, https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.2334, 2023.

Kemp, A. I. S., Vervoort, J. D., Bjorkman, K., and Iaccheri, L. M.: Hafnium isotope characteristics of Palaeoarchaean zircon OG1/PGC from the Owens Gully Diorite, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia, Geostand. Geoanal. Res., 41, 659–673, https://doi.org/10.1111/ggr.12182, 2017.

Kim, Y., Lee, E. J., Roy, S., Sharbirin, A. S., Ranz, L.-G., Dieing, T., and Kim, J.: Measurement of lateral and axial resolution of confocal Raman microscope using dispersed carbon nanotubes and suspended graphene, Curr. Appl. Phys., 20, 71–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cap.2019.10.012, 2020.

Kooymans, C., Magee Jr., C. W., Waltenberg, K., Evans, N. J., Bodorkos, S., Amelin, Y., Kamo, S. L., and Ireland, T.: Effect of chemical abrasion of zircon on SIMS U–Pb, δ18O, trace element, and LA-ICPMS trace element and Lu–Hf isotopic analyses, Geochronology, 6, 337–363, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-6-337-2024, 2024.

Lee, J. K. W. and Tromp, J.: Self-induced fracture generation in zircon, J. Geophys. Res.-Sol. Ea., 100, 17753–17770, 1995.

Lenz, C. and Nasdala, L.: A photoluminescence study of REE3+ emissions in radiation-damaged zircon, Am. Mineral., 100, 1123–1133, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2015-4894CCBYNCND, 2015.

Magee, C. W., Withnall, I. W., Hutton, L. J., Perkins, W. G., Donchak, P. J. T., Parsons, A., Blake, P. R., Sweet, I. P., and Carson, C. J.: Joint GSQ–GA geochronology project, Mount Isa Region, 2008–2009, Queensland Geological Record, 7, 1–134, 2012.

Magee Jr., C. W., Danišík, M., and Mernagh, T.: Extreme isotopologue disequilibrium in molecular SIMS species during SHRIMP geochronology, Geosci. Instrum. Method. Data Syst., 6, 523–536, https://doi.org/10.5194/gi-6-523-2017, 2017.

Magee Jr., C. W., Bodorkos, S., Lewis, C. J., Crowley, J. L., Wall, C. J., and Friedman, R. M.: Examination of the accuracy of SHRIMP U–Pb geochronology based on samples dated by both SHRIMP and CA-TIMS, Geochronology, 5, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-5-1-2023, 2023.

Magee, C. W. J.: Data for Magee et al. Technical note: Investigation into the relationship between zircon structural damage and Pb mobility using chemical abrasion, SIMS, Raman spectroscopy, and atom probe tomography, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17430613, 2025.

McKanna, A. J., Koran, I., Schoene, B., and Ketcham, R. A.: Chemical abrasion: the mechanics of zircon dissolution, Geochronology, 5, 127–151, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-5-127-2023, 2023.

McKanna, A. J., Schoene, B., and Szymanowski, D.: Geochronological and geochemical effects of zircon chemical abrasion: insights from single-crystal stepwise dissolution experiments, Geochronology, 6, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.5194/gchron-6-1-2024, 2024.

McLaren, A. C., Gerald, J. F., and Williams, I. S.: The microstructure of zircon and its influence on the age determination from isotopic ratios measured by ion microprobe. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 58, 993–1005, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(94)90521-5, 1994.

Nasdala, L., Irmer, G., and Wolf, D.: The degree of metamictization in zircons: a Raman spectroscopic study, Eur. J. Mineral., 7, 471–478, 1995.

Nasdala, L., Lengauer, C. L., Hanchar, J. M., Kronz, A., Wirth, R., Blanc, P., Kennedy, A. K., and Seydoux-Guillaume, A.-M.: Annealing radiation damage and the recovery of cathodoluminescence, Chem. Geol., 191, 121–140, 2002.

Nasdala, L., Hanchar, J. M., Rhede, D., Kennedy, A. K., and Váczi, T.: Retention of uranium in complexly altered zircon: An example from Bancroft, Ontario, Chem. Geol., 269, 290–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.10.004, 2010.

Peterman, Z. E., Zartman, R. E., and Sims, P. K.: A protracted Archean history in the Watersmeet gneiss dome, northern Michigan, Bull. U.S. Geol. Surv., 1622, 51–64, 1986.

Peterman, E. M., Reddy, S. M., Saxey, D. W., Snoeyenbos, D. R., Rickard, W. D., Fougerouse, D., and Kylander-Clark, A. R.: Nanogeochronology of discordant zircon measured by atom probe microscopy of Pb-enriched dislocation loops, Sci. Adv., 2, e1601318, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601318, 2016.

Peterman, E. M., Reddy, S. M., Saxey, D. W., Fougerouse, D., Quadir, M. Z., and Jercinovic, M. J.: Trace-element segregation to dislocation loops in experimentally heated zircon. Am. Mineral., 106, 1971–1979, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2021-7654, 2021.

Petersson, A., Kemp, A. I. S., Hickman, A. H., Whitehouse, M. J., Martin, L., and Gray, C. M.: A new 3.59 Ga magmatic suite and a chondritic source to the east Pilbara Craton, Chem. Geol., 511, 51–70, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.01.021, 2019.

Piazolo, S., La Fontaine, A., Trimby, P., Harley, S., Yang, L., Armstrong, R., and Cairney, J. M.: Deformation-induced trace element redistribution in zircon revealed using atom probe tomography, Nat. Commun., 7, 10490, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10490, 2016.

Saxey, D. W., Reddy, S. M., Fougerouse, D., and Rickard, W. D.: The optimization of zircon analyses by laser-assisted atom probe microscopy: Insights from the 91500 zircon standard, in: Microstructural Geochronology: Planetary records down to atom scale, edited by: Moser, D. E., Corfu, F., Darling, J. R., Reddy, S. M., and Tait, K., Geophysical Monograph Series, AGU, 293–313, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119227250.ch14, 2018.

Schoene, B., Crowley, J. L., Condon, D. J., Schmitz, M. D., and Bowring, S. A.: Reassessing the uranium decay constants for geochronology using ID-TIMS U-Pb data, Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac., 70, 426–445, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2005.09.007, 2006.

Stern, R. A., Bodorkos, S., Kamo, S. L., Hickman, A. H., and Corfu, F.: Measurement of SIMS instrumental mass fractionation of Pb isotopes during zircon dating, Geostand. Geoanal. Res., 33, 145–168, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-908X.2009.00023.x, 2009.

Thompson, K., Lawrence, D., Larson, D. J., Olson, J. D., Kelly, T. F., and Gorman, B.: In situ site-specific specimen preparation for atom probe tomography, Ultramicroscopy, 107, 131–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ULTRAMIC.2006.06.008, 2007.

Váczi, T.: A new, simple approximation for the deconvolution of instrumental broadening in spectroscopic band profiles, Appl. Spectrosc., 68, 1274–1278, https://doi.org/10.1366/13-07275, 2014.

Valley, J. W., Cavosie, A. J., Ushikubo, T., Reinhard, D. A., Lawrence, D. F., Larson, D. J., Clifton, P. H., Kelly, T. F., Wilde, S. A., Moser, D. E., and Spicuzza, M. J.: Hadean age for a post-magma-ocean zircon confirmed by atom-probe tomography, Nat. Geosci., 7, 219–223, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2075, 2014.

Wang, X., Hatzoglou, C., Sneed, B., Fan, Z., Guo, W., Jin, K., Chen, D., Bei, H., Wang, Y., Weber, W. J., and Zhang, Y.: Interpreting nanovoids in atom probe tomography data for accurate local compositional measurements, Nat. Commun., 11, 1022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14832-w, 2020.

Wilkes, T. J., Titchmarsh, J. M., Smith, G. D. W., Smith, D. A., Morris, R. F., Johnson, S., Godfrey, T. J., and Birdseye, P.: The fracture of field-ion microscope specimens, J. Phys. D, 5, 2226, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/5/12/312, 1972.

Zeug, M., Nasdala, L., Wanthanachaisaeng, B., Balmer, W. A., Corfu, F., and Wildner, M.: Blue zircon from Ratanakiri, Cambodia, J. Gemmol., 36, 112–132, https://doi.org/10.15506/JoG.2018.36.2.112, 2018.

Zhang, M., Salje, E. K. H., Capitani, G. C., Leroux, H., Clark, A. M., Schlüter, J., and Ewing, R. C.: Annealing of α-decay damage in zircon: a Raman spectroscopic study, J. Phys.-Condens. Matter, 12, 3131–3148, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/12/13/321, 2000.